The Resilient Echoes: Revitalizing Anishinaabemowin in Wisconsin’s Ojibwe Communities

In the dense forests and along the sparkling lakeshores of northern Wisconsin, a quiet but profound revolution is taking place. It’s a revolution not of arms, but of voices – the voices of children, youth, and adults rediscovering and reclaiming Anishinaabemowin, the Ojibwe language. Once vibrant and ubiquitous across the Great Lakes region, the language faced a century of systematic suppression, pushing it to the brink of extinction. Today, however, a tenacious network of language programs within Wisconsin’s Ojibwe communities is fighting back, nurturing new generations of speakers and ensuring that the ancient echoes of Anishinaabe wisdom continue to resonate.

The story of Anishinaabemowin is intrinsically linked to the history of the Anishinaabe people, who comprise the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi nations. For millennia, the language was the bedrock of their culture, carrying intricate knowledge of the land, spiritual teachings, governance, and social structures. It offered a unique worldview, where verbs often took precedence over nouns, reflecting a dynamic and interconnected reality. But with the arrival of European colonizers, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this linguistic heritage came under direct assault.

The devastating impact of federal Indian boarding schools, such as the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School and the Tomah Indian School in Wisconsin, cannot be overstated. Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families, punished for speaking their native tongues, and indoctrinated into English-only environments. This genocidal policy, coupled with broader societal pressures and the allure of assimilation, led to a catastrophic intergenerational language break. By the mid-20th century, the number of fluent Anishinaabemowin speakers had plummeted dramatically, with most remaining speakers belonging to the elder generation. Today, estimates suggest fewer than 5,000 fluent speakers remain worldwide, with only a fraction residing in Wisconsin, making it critically endangered.

"We lost so much," reflects Elder Margaret P. Smith, a revered speaker from the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, her voice tinged with both sorrow and determination. "My grandparents spoke it every day. My parents understood but rarely spoke it to us, fearing we’d be held back in school. And by my generation, it was almost gone. But it’s not just words; it’s our way of thinking, our connection to everything. When our language sleeps, a part of our soul sleeps."

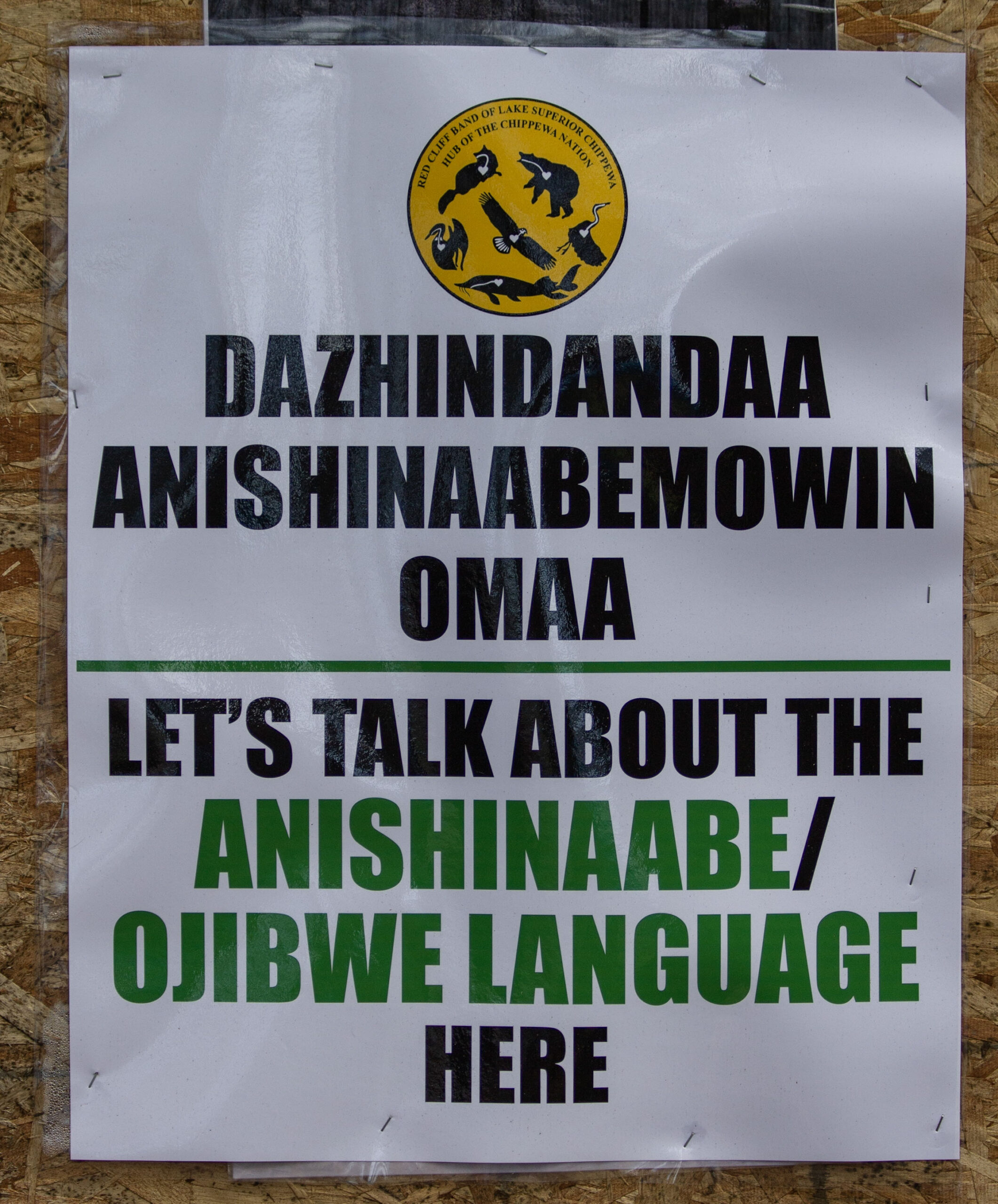

It is this profound understanding of language as the carrier of culture, identity, and sovereignty that fuels the revitalization efforts across Wisconsin’s twelve federally recognized tribes, six of which are Ojibwe bands: Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, Lac du Flambeau, Red Cliff, St. Croix, and Sokaogon Mole Lake. These communities are at the forefront of innovative programs designed to awaken the sleeping language.

One of the most celebrated examples is Waadookodaading, the Ojibwe Language Immersion School on the Lac Courte Oreilles (LCO) reservation near Hayward. Established in 2000, Waadookodaading (meaning "they help each other") is a beacon of hope, providing a full immersion experience for children from kindergarten through eighth grade. Here, every subject – math, science, history, art – is taught entirely in Anishinaabemowin. The results are nothing short of remarkable. Children emerge not only fluent in their ancestral language but also with a deeper understanding of their cultural heritage and a strong sense of identity.

"Seeing our children speak Anishinaabemowin naturally, effortlessly – it’s a miracle," says Gina King, a parent and language advocate whose children attend Waadookodaading. "It’s not just learning words; it’s learning how to be Anishinaabe in the modern world. They are connecting with their elders in a way that my generation couldn’t. They are living the language." The school’s success has inspired other communities and serves as a vital model for language revitalization nationwide.

Beyond immersion schools, a diverse array of programs is blossoming across the state:

- Community-Based Adult Classes: Many Ojibwe bands host regular evening or weekend classes for adults eager to reclaim their linguistic heritage. These classes often draw participants of all ages, from young adults to elders who wish to brush up on their childhood language. The focus is on practical communication, cultural context, and fostering a supportive learning environment. The Bad River Band, for instance, has invested heavily in community-based learning, recognizing that language revitalization must be a collective effort.

- Master-Apprentice Programs: This traditional and highly effective model pairs a fluent elder (the master) with a dedicated learner (the apprentice) for intensive, one-on-one language immersion. The pair spends hundreds of hours together, conversing solely in Anishinaabemowin, engaging in daily activities, and transferring not just vocabulary but also the nuances of conversational flow, cultural protocols, and storytelling. This method is particularly crucial for capturing the unique idiolects and wisdom of the last generation of first-language speakers.

- University Partnerships: Wisconsin’s higher education institutions are increasingly recognizing their role in supporting Indigenous language revitalization. The University of Wisconsin-Madison, for example, offers Anishinaabemowin courses, attracting both Native and non-Native students interested in the language and culture. Similarly, UW-Superior and Northland College, situated in close proximity to several Ojibwe reservations, offer Indigenous studies programs that often include language instruction, providing a crucial academic pathway for future language teachers and scholars.

- Digital Resources and Technology: Recognizing the need to reach learners beyond physical classrooms, many programs are embracing technology. Online dictionaries, language learning apps, YouTube channels featuring elders speaking Anishinaabemowin, and social media groups dedicated to the language are expanding access and making learning more engaging for younger generations. The Lac du Flambeau Band has been a leader in developing digital resources, understanding that technology can bridge geographical gaps and create new avenues for immersion.

- Summer Language Camps and Youth Programs: To instill a love for the language early on, many bands organize summer camps where children learn Anishinaabemowin through games, storytelling, crafts, and outdoor activities. These camps provide a fun, low-pressure environment for immersion and cultural connection.

Despite these inspiring successes, the path to full language revitalization is fraught with challenges. The most pressing concern remains the dwindling number of fluent elder speakers. "It’s a race against time," says Dr. Anton Treuer, an Ojibwe language scholar and professor at Bemidji State University, whose work frequently involves Wisconsin communities. "Every fluent elder we lose takes with them a library of knowledge, a unique way of understanding the world. We have to capture that knowledge and transfer it to the next generation as quickly and effectively as possible."

Funding is another perpetual hurdle. While grants and tribal resources support many initiatives, sustained, long-term funding is essential for expanding programs, training more teachers, and developing comprehensive curricula. Attracting and retaining qualified Anishinaabemowin teachers, especially those fluent enough for immersion settings, is also a significant challenge. Many of the most fluent speakers are elders who may not have formal teaching qualifications, requiring creative approaches to credentialing and support.

Moreover, overcoming the lingering effects of historical trauma is crucial. For some, the memory of punishment for speaking their language can still evoke feelings of shame or reluctance. Language programs must work to heal these wounds, fostering environments where speaking Anishinaabemowin is celebrated and seen as a source of pride and strength.

Yet, the momentum for revitalization is undeniable. "The spirit of our language is awakening," says Kevin Dupuis, an Anishinaabemowin instructor at the St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin. "We’re not just teaching words; we’re teaching resilience, identity, and a pathway back to who we truly are as Anishinaabe people. Every new speaker is a victory, a testament to the strength of our ancestors."

The future of Anishinaabemowin in Wisconsin depends on the continued dedication of these communities, the unwavering commitment of elders and educators, and the enthusiastic embrace of younger generations. It requires a holistic approach that integrates language into every aspect of community life – from tribal government meetings to everyday conversations in homes and schools. The dream is to reach a point where Anishinaabemowin is not just a language learned in classrooms, but a living, breathing part of daily existence, a natural medium for expressing joy, sorrow, wisdom, and love.

As the sun sets over the ancient lands of the Anishinaabe in Wisconsin, the soft murmur of Anishinaabemowin spoken by a child, an elder, or a diligent learner, is more than just sound. It is a powerful affirmation of cultural survival, a vibrant thread weaving the past into the present, and a hopeful promise for the future. The echoes of the Ojibwe language, once muted, are growing stronger, resonating with the enduring spirit of a people determined to speak their truth into existence.