Echoes of the Birch Forest: The Enduring Legacy of the Ojibwe in the Great Lakes

The vast, shimmering expanse of the Great Lakes, with its ancient shores, whispering pines, and abundant waters, has been home to the Anishinaabe people – known to the wider world as the Ojibwe or Chippewa – for millennia. Their history is not merely a chronicle of events, but a living tapestry woven from profound spiritual connection to the land, remarkable resilience in the face of immense adversity, and an unwavering commitment to their cultural identity. From their earliest migrations to their contemporary struggles for sovereignty and self-determination, the Ojibwe story is an indispensable chapter in the history of North America, echoing through the birch forests and across the freshwater seas.

The origins of the Ojibwe are rooted in ancient prophecies and a remarkable migration. According to the Seven Fires Prophecy, a central narrative in Anishinaabe oral tradition, the people journeyed westward from the Atlantic coast, guided by visions and stopping at seven significant locations. Their ultimate destination, foretold to be a place where "food grows on water," led them to the Great Lakes region, where manoomin (wild rice) thrived in the shallow waters. This journey culminated around the spiritual heartland of Mooningwanekaaning (Madeline Island) in Lake Superior, establishing a powerful connection to the land that persists to this day. The Ojibwe, often referred to as "Keepers of the Sacred Fire" within the larger Anishinaabe confederacy (which includes the Odawa and Potawatomi), developed a sophisticated society adapted perfectly to their environment.

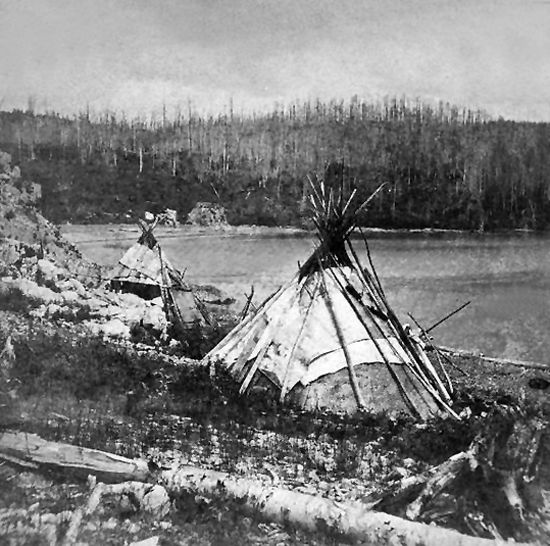

Pre-contact Ojibwe life was characterized by a deep understanding of their ecosystem and a seasonal rhythm dictated by the land’s bounty. They were master navigators and engineers, crafting the iconic birchbark canoe – a lightweight, durable vessel that allowed them to traverse the intricate network of lakes and rivers. Their intimate knowledge of plants and animals sustained them: they hunted deer, moose, and bear, fished extensively, gathered berries, nuts, and maple sap, and, crucially, harvested manoomin. "Manoomin is not just food; it’s a gift from the Creator, a central part of our identity and our spiritual connection to this land," an elder once explained, underscoring its sacred significance. Their villages were typically dispersed in winter for hunting and trapping, then coalesced in larger summer encampments for fishing, harvesting, and communal ceremonies. Societal structure was organized around clans, often represented by animal totems, fostering kinship and collective responsibility. The Midewiwin, or Grand Medicine Society, served as the primary institution for spiritual guidance, healing, and the preservation of ancient knowledge, maintaining detailed historical records and teachings through mnemonic scrolls.

The arrival of Europeans in the 17th century marked a profound turning point. The French, seeking furs, established trade relationships with the Ojibwe, transforming their economy and introducing new technologies. Metal tools, firearms, and European trade goods quickly became integrated into Ojibwe life, while beaver pelts became a highly sought-after commodity. This initial period of interaction was often one of mutual benefit, with the Ojibwe acting as crucial intermediaries in the vast fur trade network, guiding traders, providing furs, and maintaining strategic alliances. However, the contact also brought devastating consequences, most notably the introduction of European diseases like smallpox, which decimated communities lacking natural immunities. The Ojibwe’s strategic location and formidable reputation, however, allowed them to expand their territory, pushing back against rival nations like the Dakota (Sioux) and establishing a dominant presence across the western Great Lakes.

As the colonial powers shifted – from French to British and eventually to American dominance – so too did the pressures on the Ojibwe. The American desire for land, fueled by westward expansion and the concept of "manifest destiny," led to a brutal era of treaties. Between the late 18th and mid-19th centuries, the Ojibwe were compelled to sign numerous treaties, often under duress or through deceptive practices, ceding vast tracts of their ancestral lands in exchange for annuities, goods, and the establishment of reservations. These reservations, often mere fragments of their former domain, were intended to isolate and "civilize" Indigenous peoples, opening up the land for Euro-American settlement and resource extraction. The Treaty of La Pointe in 1854, for example, saw the Ojibwe bands of Lake Superior and the Mississippi cede millions of acres, but critically, it also reserved certain rights, including hunting, fishing, and gathering on ceded territories – rights that would become central to future legal battles.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought an intensified campaign of assimilation. Federal policies, encapsulated by the infamous phrase "kill the Indian, save the man," aimed to dismantle Indigenous cultures and integrate individuals into mainstream American society. Boarding schools, often run by religious institutions, forcibly removed Ojibwe children from their families, forbidding them from speaking their language, practicing their spiritual traditions, or wearing traditional clothing. The trauma inflicted by these institutions, designed to erase their identity, had profound and lasting effects on generations, contributing to cycles of intergenerational trauma that many communities are still grappling with today. The Dawes Act of 1887 further fragmented tribal lands by allotting communal property to individual tribal members, often leading to the loss of land to non-Native buyers.

Despite these relentless pressures, the Ojibwe spirit of resilience endured. Many traditions, ceremonies, and the Ojibwe language (Anishinaabemowin) were preserved through clandestine means, passed down quietly by elders determined to keep their heritage alive. The mid-20th century saw a growing movement for Native American rights, which gathered momentum through the American Indian Movement (AIM) and various tribal sovereignty efforts. The Ojibwe were at the forefront of many of these struggles, particularly in asserting their treaty-reserved rights. Landmark court cases throughout the 1970s and 80s, such as the Voigt and Lac Courte Oreilles v. Wisconsin cases, reaffirmed Ojibwe off-reservation hunting, fishing, and gathering rights, leading to highly publicized spearfishing controversies but ultimately strengthening tribal sovereignty and resource management.

Today, the Ojibwe nations across the Great Lakes region are vibrant and dynamic communities, actively engaged in reclaiming and revitalizing their cultures, languages, and economies. Language immersion programs are working tirelessly to teach Anishinaabemowin to younger generations, recognizing that language is a vital vessel for cultural transmission. Cultural centers, powwows, and traditional ceremonies celebrate their rich heritage, while elders continue to be revered as invaluable sources of wisdom and knowledge.

Economically, many Ojibwe tribes have diversified their enterprises, from gaming operations that provide crucial revenue for social programs, healthcare, and education, to forestry, tourism, and sustainable resource management. They are increasingly asserting their sovereignty over natural resources, drawing upon traditional ecological knowledge to protect the environment and manage lands and waters within their ancestral territories. Challenges remain, including the enduring impacts of historical trauma, poverty, inadequate infrastructure, and ongoing battles against systemic racism and environmental threats to their lands and waters. However, the Ojibwe continue to advocate for self-determination, honoring the promises of treaties, and ensuring a vibrant future for their people.

The history of the Ojibwe in the Great Lakes is a testament to the enduring power of culture, the strength of a people deeply connected to their land, and the unyielding human spirit. From the ancient migration guided by prophecy to the modern-day struggle for justice and revitalization, their narrative is not one of a vanished past, but of a tenacious and thriving present, forever interwoven with the majestic landscape of the Great Lakes, where the echoes of the birch forest continue to sing their story.