The Vanishing Silver: Northern California’s Salmon Economy and the Battle for River Rights

Northern California’s identity is inextricably linked to its wild salmon. For millennia, the annual return of Chinook, Coho, and Steelhead salmon has not only sustained vibrant ecosystems but also forged the bedrock of economies and cultures, particularly among Indigenous communities. Today, this vital connection hangs by a thread, caught in a desperate struggle over water rights, environmental degradation, and the relentless march of climate change. The once-thriving salmon-based economy, a multi-million dollar industry supporting thousands of jobs, faces existential threats, pushing an entire way of life to the brink.

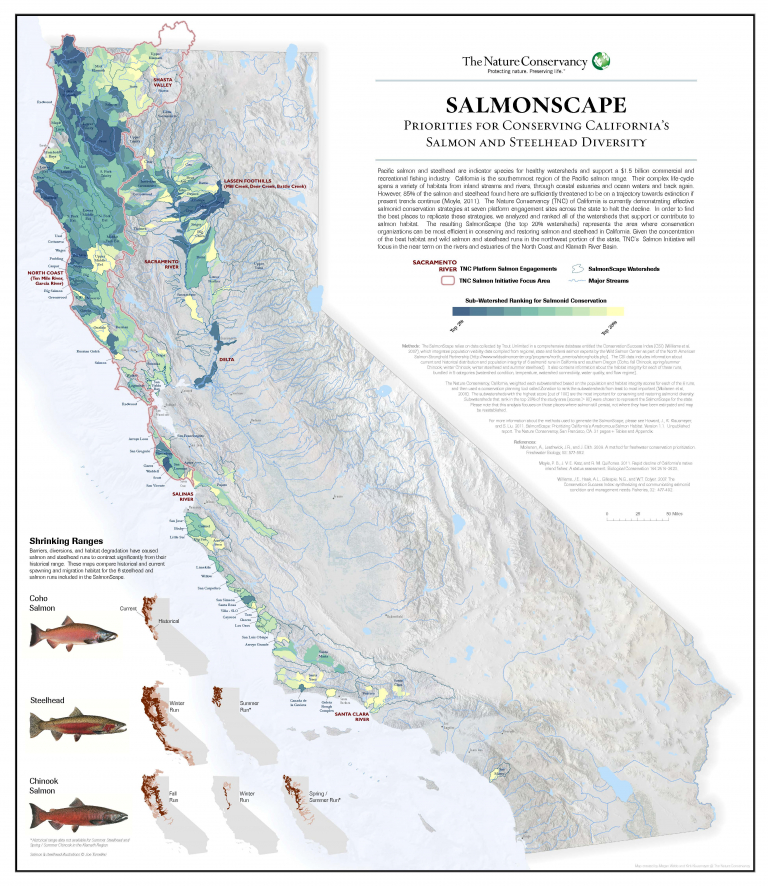

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, the Klamath River Basin, and the myriad of coastal rivers that drain into the Pacific are the lifeblood of this unique ecosystem. These waterways are the migratory highways and spawning grounds for salmon, which embark on incredible journeys from the ocean, returning to the very gravel beds where they were born. Their epic migrations are not just biological marvels; they are economic engines.

The Economic Tide: From Abundance to Scarcity

For generations, commercial salmon fishing has been a cornerstone of coastal towns from Fort Bragg to San Francisco. Fleets of small boats, often family-owned, would ply the waters, their catches destined for restaurants, markets, and processors, creating a ripple effect through local economies. Every salmon caught, whether for commercial or recreational purposes, generates a chain of economic activity: bait and tackle sales, fuel purchases, boat maintenance, processing, transportation, and restaurant patronage.

"It’s not just about the fish; it’s about everything that surrounds it," explains Sarah Jensen, a third-generation commercial fisher from Bodega Bay. "When the season is open and the fish are running, our docks are bustling. Marinas are full, local businesses thrive. But when they close the season, like they did last year, it’s like a ghost town. My boat sits idle, my crew is out of work, and I’m looking at years of debt with no way to pay it back."

Indeed, the economic impact is staggering. While precise annual figures fluctuate wildly with fishing seasons, historical estimates suggest the California salmon industry, encompassing commercial and recreational fishing, processing, and associated tourism, could contribute hundreds of millions of dollars to the state’s economy and support thousands of direct and indirect jobs in good years. Recreational fishing alone attracts tourists from across the globe, eager to test their skill against the powerful fish, pouring money into guide services, charter boats, lodging, and local shops. The absence of salmon translates directly into lost revenue, shuttered businesses, and shattered livelihoods.

The Battle for Water: A Zero-Sum Game?

The precipitous decline of Northern California’s salmon populations is not a mystery; it’s a direct consequence of decades of human intervention in their habitats, primarily through the diversion and damming of rivers for agriculture and urban use. The central conflict lies in the allocation of water – a finite resource increasingly strained by a growing population and a changing climate.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a vast network of sloughs and channels that serves as the heart of California’s water delivery system, is a critical bottleneck. Giant pumps divert massive amounts of water from the Delta to the arid Central Valley for agriculture and to Southern California cities. These diversions create powerful currents that disorient migrating salmon, drawing them into canals where they perish. Furthermore, reduced freshwater flows lead to warmer water temperatures, which are lethal to salmon eggs and juveniles, and allow saltwater intrusion, further degrading freshwater habitats.

"We’ve turned our rivers into plumbing systems," laments Dr. Ken Smith, a fisheries biologist who has studied California salmon for over 30 years. "The engineers prioritized water delivery over ecosystem health, and the salmon are paying the ultimate price. We need to acknowledge that rivers are living systems, not just conduits for human consumption."

The situation is exacerbated by California’s complex and often archaic water rights system, which prioritizes senior water rights holders – many of whom are large agricultural operations – even in times of severe drought. This often leaves insufficient water in rivers for environmental flows, especially during critical salmon spawning and outmigration periods. The result is dangerously low and warm river levels, leading to catastrophic die-offs. In 2021, the vast majority of juvenile winter-run Chinook salmon in the Sacramento River, an endangered species, perished due to high water temperatures.

Tribal Sovereignty and the Fight for "First Foods"

For the Indigenous peoples of Northern California – including the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa tribes – salmon are more than an economic commodity; they are a sacred "first food," central to their spiritual beliefs, cultural practices, and identity. The right to fish for salmon is a treaty right, a sovereign guarantee that pre-dates the state of California. The decline of salmon represents not just an economic hardship but a profound cultural wound, an environmental injustice that threatens thousands of years of heritage.

"Our world revolves around the salmon," states Sammy Gensaw III, a Yurok tribal member and advocate for river restoration. "They are our teachers, our providers, our connection to our ancestors. When the salmon are sick, we are sick. When the river is dying, our people are dying. This isn’t just about fishing; it’s about who we are."

The Klamath River Basin provides a potent example of this struggle and a glimmer of hope. For over a century, a series of four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath blocked salmon migration, devastated fish populations, and impacted the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa tribes, whose spiritual and sustenance practices revolved around the river. After decades of relentless advocacy by tribes, environmental groups, and fishing communities, the largest dam removal project in U.S. history is now underway on the Klamath. This monumental effort aims to restore hundreds of miles of spawning habitat and represents a critical step towards ecological and cultural healing. It stands as a testament to the power of perseverance and the importance of recognizing tribal sovereignty in environmental decision-making.

Climate Change: The Ultimate Multiplier

Adding another layer of urgency to this already precarious situation is climate change. Northern California is experiencing more frequent and intense droughts, leading to diminished snowpack – the natural reservoir for river flows – and warmer river temperatures. Wildfires, also intensified by climate change, further degrade water quality through ash and sediment runoff, and destroy riparian habitats critical for salmon.

"Climate change isn’t just a future threat; it’s here, and it’s devastating," says Dr. Smith. "Warmer oceans reduce food availability, and warmer, lower rivers create death traps. We’re seeing unprecedented challenges that compound all the historical impacts. We can’t afford to keep managing water like it’s 1950."

The cumulative effect of dams, diversions, pollution, habitat loss, and now climate change has pushed these iconic fish to the brink. Several salmon runs, like the Sacramento River winter-run Chinook and Central Valley spring-run Chinook, are listed under the Endangered Species Act, their numbers so low that entire fishing seasons are regularly canceled to protect the few remaining spawners.

Paths Forward: Restoration, Reallocation, and Resilience

The fight for Northern California’s salmon and the economy they support is a multifaceted battle, playing out in courtrooms, legislative chambers, and on the rivers themselves. Solutions are complex and often contentious, requiring a fundamental shift in how California views and manages its most precious resource: water.

Key strategies include:

- Dam Removal and Modification: Beyond the Klamath, some advocates push for the removal of other outdated or ecologically damaging dams, while others focus on modifying existing dams to improve fish passage and environmental flows.

- Habitat Restoration: Efforts to restore degraded spawning and rearing habitats, including floodplain reconnection, gravel augmentation, and riparian planting, are crucial for salmon recovery.

- Smarter Water Management: This involves re-evaluating senior water rights, implementing more flexible water allocations that prioritize environmental flows during critical periods, and investing in water conservation and efficiency measures across all sectors.

- Legal and Political Advocacy: Fishermen, tribes, and environmental groups continue to use legal challenges and political pressure to advocate for policies that protect salmon and their habitats.

- Climate Resilience: Investing in strategies that help salmon cope with a warmer, drier future, such as cold water refugia projects and improved drought planning.

The future of Northern California’s salmon-based economy and the health of its rivers hangs in the balance. It is a story not just about fish, but about the profound choices societies make regarding resource allocation, environmental stewardship, and cultural preservation. The "vanishing silver" serves as a stark warning and a powerful call to action: to secure a future where the iconic salmon can once again thrive, and with them, the communities and cultures that have depended on them for millennia. The struggle for river rights is, at its core, a struggle for the soul of Northern California.