Guardians of Diné Wisdom: The Navajo Nation’s Urgent Quest to Protect Traditional Knowledge

The Navajo Nation, or Diné Bikéyah, spanning over 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, is engaged in a profound and urgent struggle: the protection of its vast and intricate body of traditional knowledge (TK). This isn’t merely an academic exercise or a nostalgic yearning for the past; it is a fundamental assertion of sovereignty, cultural survival, and the well-being of its people. Diné traditional knowledge, known as K’é, is not merely information but a holistic way of life, intrinsically linked to the land, language, ceremonies, and the very identity of the Diné people. Its preservation is paramount in an era marked by accelerating cultural erosion, commercial exploitation, and environmental threats.

Diné traditional knowledge encompasses a comprehensive and interconnected web of ecological, spiritual, linguistic, and practical wisdom passed down through generations. It includes sophisticated understanding of astronomy, herbal medicine, sustainable agriculture, land management, water conservation, ceremonial practices, oral histories, songs, stories, weaving patterns, silversmithing techniques, and the complex philosophical framework of Hózhǫ́ – the concept of walking in beauty, balance, and harmony. For the Navajo, knowledge is not compartmentalized; it is a living system that guides their relationship with the natural world, their community, and the spiritual realm. This holistic view contrasts sharply with Western knowledge systems, making its protection challenging within existing legal frameworks.

The threats to this invaluable heritage are multifaceted and pervasive. One of the most insidious is the commercial appropriation and exploitation of Diné cultural elements. Navajo designs, symbols, and narratives are frequently copied, marketed, and sold by non-Natives without consent, attribution, or benefit-sharing. This ranges from fashion lines mimicking traditional weaving patterns to jewelry designs, and even the unauthorized use of sacred stories or ceremonial elements in popular culture. Such appropriation not only devalues the original creators and their cultural significance but also directly undermines the economic livelihoods of Navajo artisans who depend on their authentic creations. The lack of robust legal mechanisms tailored to protect collective indigenous intellectual property leaves the Navajo Nation vulnerable to these predatory practices.

Beyond commercial exploitation, academic and scientific institutions have historically extracted knowledge from indigenous communities without adequate informed consent, reciprocity, or benefit-sharing. Researchers, ethnobotanists, anthropologists, and linguists have often collected information, published findings, and built careers on Diné knowledge, while the community itself received little to no direct benefit, and sometimes even suffered harm through the misrepresentation or desacralization of their traditions. This legacy of extractive research has fostered deep distrust and necessitates a complete paradigm shift in how external entities engage with indigenous knowledge holders.

Perhaps the most critical threat, however, is the precipitous decline of the Navajo language (Diné Bizaad). The language is the primary vessel for transmitting traditional knowledge. Intricate ceremonial instructions, medicinal plant names, specific agricultural techniques, and the nuanced philosophical concepts like Hózhǫ́ are deeply embedded within the linguistic structure and cannot be fully translated or understood outside of Diné Bizaad. Generations of forced assimilation policies, including boarding schools that punished children for speaking their native tongue, have severely impacted language fluency. While revitalization efforts are underway, the loss of fluent speakers directly correlates with the erosion of the traditional knowledge they carry. As one elder poignantly stated, "When the language goes, the knowledge goes with it."

In response to these pervasive threats, the Navajo Nation is actively pursuing a range of strategies for traditional knowledge protection, demonstrating remarkable resilience and self-determination.

1. Legal and Policy Frameworks:

Recognizing the inadequacy of Western intellectual property (IP) laws – which typically focus on individual ownership, novelty, and limited duration – the Navajo Nation is exploring and developing sui generis (unique) legal frameworks. These frameworks aim to protect collective ownership, perpetual duration, and the sacred nature of certain knowledge. The Nation is working to establish tribal ordinances that define traditional knowledge, assert tribal ownership, regulate its use, and stipulate protocols for prior informed consent (PIC) and benefit-sharing for any external entities wishing to engage with Diné knowledge. This includes developing culturally appropriate research ethics guidelines that prioritize community input and control.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), though non-binding, serves as a crucial international framework. Article 31 of UNDRIP explicitly states: "Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions." The Navajo Nation leverages such international instruments to advocate for stronger national and international protections and to guide its own internal policy development.

2. Language Revitalization:

Central to TK protection is the revitalization of Diné Bizaad. Institutions like Diné College, the first tribally controlled college in the United States, play a pivotal role. They offer comprehensive Diné language immersion programs, curriculum development, and teacher training. Community-based initiatives, intergenerational teaching programs, and the creation of Diné language media (radio, television, online content) are also critical. The aim is not just to teach the language as a subject, but to immerse youth in environments where Diné Bizaad is the living, breathing medium for transmitting cultural knowledge, stories, and ceremonies. The legacy of the Navajo Code Talkers during World War II stands as a powerful testament to the strategic and invaluable nature of the Diné language, highlighting its unique structure and resilience.

3. Documentation and Archiving (with Caution):

While some traditional knowledge is sacred and meant to remain within the community, certain aspects can be documented and archived for internal community use and future generations, provided it is done with extreme caution and community oversight. This involves working with elders and cultural experts to record oral histories, traditional narratives, medicinal plant uses, and ceremonial protocols. The critical distinction here is "for internal use" – these archives are not for public dissemination or commercial exploitation, but rather as resources for Diné people to reclaim and transmit their heritage. Protocols for access, consent, and storage are meticulously developed to prevent misuse.

4. Intergenerational Transmission and Cultural Education:

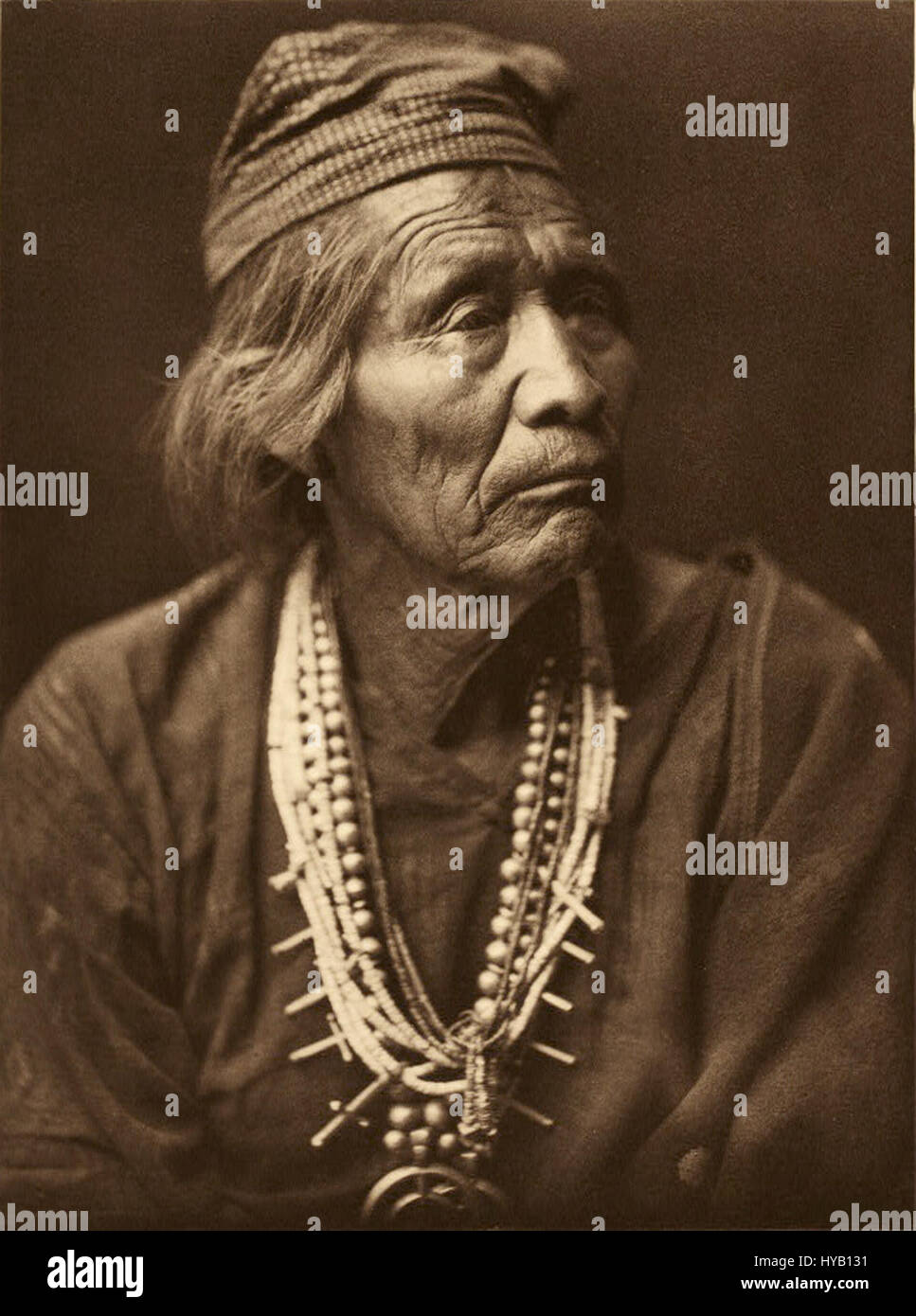

Elders are the living repositories of Diné wisdom. Efforts are focused on creating opportunities for elders to mentor and teach youth directly. This includes cultural camps, traditional arts and crafts workshops (weaving, silversmithing, pottery), storytelling sessions, and ceremonies. Schools within the Navajo Nation are increasingly integrating Diné cultural curriculum, teaching about traditional governance, environmental stewardship, and the philosophical underpinnings of Diné life. This ensures that traditional knowledge is not just preserved in books but continues as a living, evolving practice.

5. Protecting Sacred Sites and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK):

The Navajo landscape itself is imbued with sacred meaning and is a vital component of traditional knowledge. Efforts to protect sacred sites from desecration, resource extraction, and development are ongoing. Furthermore, Diné Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) – an intricate understanding of local ecosystems, plant life, animal behavior, and sustainable resource management – is being recognized for its immense value in addressing contemporary environmental challenges like climate change and water scarcity. The Navajo Nation seeks to integrate TEK into modern land and resource management practices, asserting their right to manage their ancestral lands according to their own principles.

The path to fully protecting Diné traditional knowledge is fraught with challenges. It requires sustained funding, political will, and continuous engagement with both internal community dynamics and external legal and commercial pressures. There are ongoing debates within the community about what knowledge can be shared, what must remain sacred and private, and how to balance the need for preservation with the dangers of commodification.

Ultimately, the protection of Diné traditional knowledge is not merely an academic exercise or a nostalgic pursuit; it is a vital assertion of self-determination and a testament to the resilience of a people. It is about ensuring that future generations of Diné can continue to walk in Hózhǫ́, guided by the wisdom of their ancestors, connected to their land, language, and identity. In an increasingly homogenized world, the unique insights and sustainable practices embedded within Diné traditional knowledge offer invaluable lessons for all humanity, making its preservation not just a Navajo concern, but a global imperative. The Navajo Nation stands as a beacon of cultural fortitude, demonstrating that the future of indigenous wisdom lies in active protection, revitalization, and sovereign control.