The Enduring Weave: Understanding Navajo Nation’s Traditional Governance

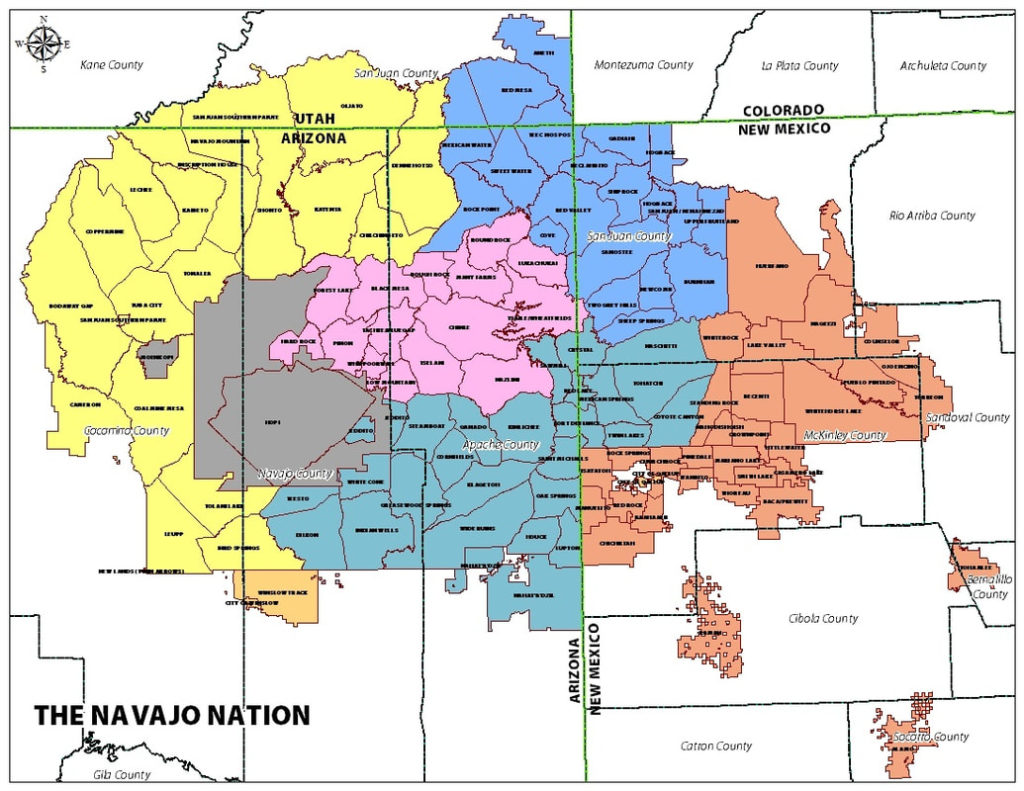

The Navajo Nation, or Diné Bikéyah as it is known to its people, sprawls across more than 27,000 square miles of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah – an area larger than 10 U.S. states. This vastness is matched by the depth and complexity of its governance, a system not merely administrative but deeply interwoven with cultural philosophy, kinship, and an enduring commitment to harmony. While contemporary structures exist, the bedrock of Navajo Nation’s governance remains its traditional principles, a testament to resilience and an adaptive spirit that has navigated centuries of change.

At the heart of Diné traditional governance lies the concept of Hózhó, a holistic philosophy that encompasses beauty, balance, harmony, and order. Hózhó is not just an aesthetic ideal but a guiding principle for life, health, and social interaction. Every decision, every conflict resolution, and every leadership role traditionally aimed to restore or maintain Hózhó. This principle dictates that all things are interconnected, and a disruption in one area affects the whole. Governance, therefore, is not about control or power, but about maintaining the delicate balance within the community, with nature, and with the spiritual world.

Integral to Hózhó is K’é, the intricate system of kinship and relatedness. The Diné social structure is fundamentally matrilineal, meaning identity and clan affiliation are traced through the mother. Every individual belongs to four clans: their mother’s clan, their father’s clan, their maternal grandfather’s clan, and their paternal grandfather’s clan. This intricate web of relationships extends beyond immediate family, encompassing the entire Diné community. K’é establishes a profound sense of responsibility and mutual obligation. You are not merely an individual; you are a nexus of relationships.

This clan system is not just for social identification; it is a foundational element of traditional governance. It dictates who can marry whom, who is responsible for whom, and how disputes are mediated. When a conflict arises, the first recourse is often to involve clan relatives from both sides, leveraging the inherent trust and obligation within K’é to find a resolution. This decentralized approach emphasizes community-owned solutions over top-down directives. As one Diné elder succinctly put it, "Our clans are our constitution. They tell us how to relate, how to help each other, and how to make things right."

Traditional leadership, personified by the Naat’áanii (or headmen/women), emerged organically from within these clan structures. Unlike Western models of elected officials, Naat’áanii were not chosen by popular vote but recognized for their wisdom, eloquence, integrity, spiritual knowledge, and ability to mediate and articulate the community’s consensus. They were often skilled speakers, negotiators, and peacemakers, whose authority stemmed from respect and their capacity to lead by example and persuasion, rather than by force. Their role was to facilitate discussion, guide the community towards consensus, and ensure decisions aligned with Hózhó. A Naat’áanii’s power was not about individual authority but about their ability to embody and articulate the collective will and wisdom of the people.

Decision-making in traditional Diné society was fundamentally consensus-based. Meetings, often held outdoors, involved extensive discussion where everyone had an opportunity to speak. The goal was not a simple majority vote but a process of deliberation and negotiation until a common understanding and agreement could be reached. This process, while sometimes lengthy, ensured that all voices were heard, all perspectives considered, and the resulting decision had the full backing of the community, fostering unity rather than division.

The traditional justice system also deeply reflected Hózhó and K’é. It was largely restorative, focusing on repairing harm and restoring balance rather than punishment. When an offense occurred, the emphasis was on bringing the involved parties and their respective clans together to talk, understand the impact of the actions, and agree upon a restitution that would heal the rupture in the community. Peacemaking, known as Hózhóójí Naat’áanii, was (and continues to be) a core component. Peacemakers, respected individuals with deep knowledge of Diné common law and cultural values, facilitated dialogue, guided individuals towards reconciliation, and helped them understand their responsibilities to one another and the community. The goal was to re-establish harmony and ensure the well-being of all involved, contrasting sharply with retributive Western justice systems.

The arrival of European colonizers and the subsequent establishment of the United States significantly impacted Diné governance. Treaties were signed, often under duress, and the U.S. government, through agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), attempted to impose its own administrative structures. The creation of a central Navajo Tribal Council in the early 20th century, initially to negotiate oil leases, marked a significant departure from traditional, decentralized governance. This council evolved, often under pressure from federal policies like the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which encouraged tribes to adopt Western-style constitutions.

Despite these external pressures and the evolution towards a more formalized, three-branch government – Executive, Legislative (the Navajo Nation Council), and Judicial – the traditional underpinnings have never been fully abandoned. They persist, influencing and often guiding the contemporary system. The Navajo Nation Council, for instance, has undergone significant changes, most notably a reduction from 88 delegates to 24 in 2010, reflecting a move towards greater efficiency while still aiming for broad representation. Yet, even within these modern bodies, the principles of consensus, kinship, and the pursuit of Hózhó often inform discussions and decisions.

Perhaps the most direct contemporary embodiment of traditional governance principles can be found at the local level: the Chapter Houses. The Navajo Nation is divided into 110 Chapters, which function much like local municipal governments. These Chapters are the most accessible level of governance for many Diné citizens and often serve as the primary venues where traditional consensus-building, community participation, and the spirit of K’é are most actively practiced. Chapter meetings involve robust discussion, and local leaders are often expected to demonstrate the wisdom and community-mindedness akin to the traditional Naat’áanii. They bridge the gap between the central government and the everyday lives of the people, ensuring that local concerns and traditional values are heard and represented.

Furthermore, the Navajo Nation’s judicial branch has formally incorporated traditional practices. The Navajo Peacemaking Courts, established within the modern court system, offer an alternative to adversarial proceedings. These courts are presided over by community-appointed peacemakers who use traditional Diné common law and cultural practices to resolve disputes, focusing on healing, reconciliation, and restoring relationships. This innovative blend of ancient wisdom and modern legal structure demonstrates the Diné Nation’s commitment to preserving its cultural heritage while adapting to contemporary needs. As former Navajo Nation Chief Justice Robert Yazzie stated, "Peacemaking seeks to achieve harmony and balance in the community, not just to determine guilt or innocence."

The enduring strength of Navajo Nation’s governance lies in its adaptability and its unwavering connection to its core cultural values. It navigates the complexities of modern nation-building – economic development, resource management, healthcare, education – while constantly striving to ground these efforts in the wisdom of its ancestors. The challenges are immense: balancing traditional land use with industrial demands, preserving language and culture in a globalized world, and ensuring that economic progress does not come at the expense of community well-being or Hózhó.

Yet, the Diné people have consistently demonstrated their capacity to integrate the old with the new, to evolve without abandoning their essence. The traditional governance structure, with its emphasis on kinship, consensus, and harmony, provides a powerful framework for self-determination and sovereignty. It stands as a profound example of how a nation can maintain its unique identity and cultural integrity, not by rejecting modernity, but by filtering it through an ancient, resilient, and deeply meaningful system of order and beauty. The weave of Diné governance continues to evolve, but its foundational threads remain steadfast, strong, and vibrant.