Navajo Nation’s Culinary Canvas: More Than Meals, It’s a Movement

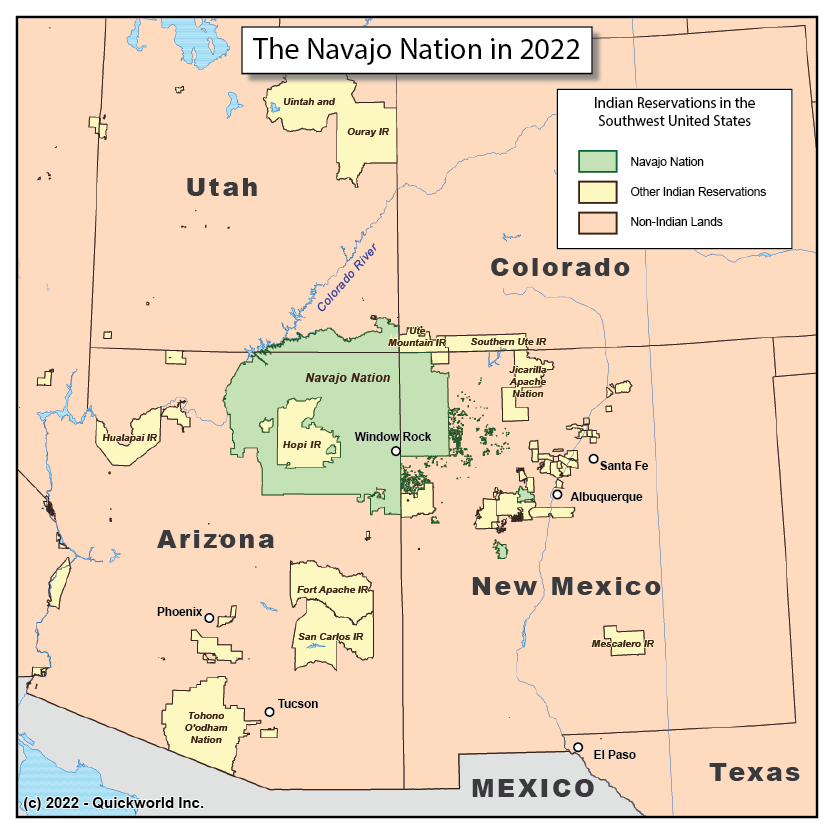

On the vast, sacred landscapes of the Navajo Nation, a culinary revolution is quietly simmering. Spanning over 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, the Diné (Navajo people) have long nourished themselves from the land. Today, the restaurants and eateries dotting this immense territory are far more than mere stops for sustenance; they are vital cultural anchors, economic engines, and vibrant classrooms where the story of a resilient people is told through every dish. In Arizona alone, from the bustling towns of Tuba City and Window Rock to the remote outposts near Monument Valley, these establishments offer a unique window into Diné heritage, innovation, and community spirit.

The culinary scene on the Navajo Nation is deeply rooted in history and adaptation. For centuries, the Diné relied on subsistence farming, hunting, and gathering, cultivating staple crops like corn, beans, and squash, and herding sheep introduced by the Spanish. This connection to the land and its bounty forms the bedrock of traditional Navajo cuisine. Mutton, a dietary staple, is celebrated in various forms: roasted, stewed, or ground for savory meatballs. Blue corn, revered for its nutritional value and spiritual significance, appears in a range of dishes, from nourishing porridges and ceremonial breads to modern interpretations like blue corn pancakes. Piñon nuts, wild spinach, and chili peppers further enrich the flavor profile, creating a cuisine that is both hearty and deeply flavorful.

Perhaps the most iconic, and often debated, symbol of Navajo cuisine is fry bread. Golden, puffy, and endlessly versatile, fry bread serves as the base for the immensely popular Navajo taco, topped with ground meat, beans, lettuce, tomatoes, and cheese. Its origins, however, are complex. Born out of necessity during the forced relocation of the Diné in the 1860s – the "Long Walk" – and subsequent reliance on government-issued rations of flour, sugar, and lard, fry bread embodies both resilience and the painful legacy of colonialism. Yet, it has been embraced and transformed into a powerful emblem of identity and cultural survival. "Fry bread tells a story of our strength, our ability to adapt and make something beautiful even from hardship," says Lena Nez, a cultural educator based near Ganado, Arizona. "It’s a comfort food, a celebration food, and a reminder of where we’ve come from."

From bustling roadside stands offering steaming bowls of green chili stew and puffy fry bread tacos to more established sit-down restaurants catering to both locals and the increasing numbers of tourists drawn to the Nation’s majestic landscapes, the dining experiences are diverse. In towns like Tuba City, a key hub in northern Arizona, establishments like the Hogan Family Restaurant offer classic Navajo comfort food alongside American diner staples, serving as community gathering places where families share meals and news. In Window Rock, the capital of the Navajo Nation, restaurants might feature a more contemporary take on traditional ingredients, reflecting a burgeoning "New Native American" cuisine that honors heritage while embracing modern culinary techniques.

One such establishment might be a fictionalized "Diné Table," where Chef Kian Begay experiments with fusion. "Our ancestors were innovators," Begay might explain, "using what was available and making it delicious. I try to do the same. We might serve a slow-braised mutton stew with roasted seasonal vegetables grown locally, or blue corn crusted salmon with a chili-lime vinaigrette. It’s about celebrating our ingredients in new ways, inviting people to experience the depth of our food culture." This approach not only tantalizes the palate but also educates diners about the versatility and richness of indigenous ingredients.

Beyond its cultural resonance, the culinary scene on the Navajo Nation is a significant economic driver. Restaurants provide crucial employment opportunities in an area where jobs can be scarce. They support local farmers, ranchers, and artisans who supply ingredients, from fresh produce and mutton to traditional blue cornmeal. For tourists, often en route to iconic sites like Monument Valley or Canyon de Chelly, these eateries offer an authentic taste of the region, transforming a simple meal into an immersive cultural experience. This connection to tourism is vital, bringing external revenue into the Nation and fostering a greater understanding of Diné life.

Yet, operating and thriving within the Navajo Nation’s food landscape comes with its unique set of challenges. Large swaths of the Nation are considered "food deserts," with limited access to fresh, affordable produce and healthy food options. This scarcity contributes to significant health disparities, including high rates of diabetes and heart disease among the Diné people. "It’s a daily struggle for many families to access nutritious food," notes Dr. Alice Yazzie, a public health advocate in Arizona. "Our restaurants play a role not just in feeding people, but in promoting healthier traditional diets and educating our communities about the benefits of eating locally and traditionally." Efforts are underway to revitalize traditional farming practices and establish farmers’ markets, creating a more robust and localized food system.

Infrastructure can also be a hurdle. Access to reliable electricity, water, and broadband internet – essential for modern business operations, particularly for ordering supplies and processing payments – can be inconsistent in remote areas. Despite these hurdles, a spirit of resilience and innovation permeates the Navajo culinary world. Many entrepreneurs operate food trucks and mobile kitchens, allowing them to reach communities beyond established towns and participate in local fairs and events, bringing their culinary offerings directly to the people.

The experience of dining on the Navajo Nation is ultimately about more than just the food on the plate; it’s about the people, the hospitality, and the profound sense of place. Whether it’s the friendly banter at a roadside stand, the quiet dignity of a family-run diner, or the vibrant atmosphere of a more contemporary restaurant, guests are often treated with a warmth and sincerity that reflects the Diné concept of Hózhó – a state of balance, harmony, and beauty. Conversations might range from local news to discussions about Diné language and traditions, providing an informal education that deepens appreciation for the culture.

The future of Navajo Nation restaurants in Arizona looks promising, marked by a growing pride in indigenous foodways and a desire to share them with the world. There’s a noticeable trend towards incorporating more traditional, healthier ingredients, reviving ancient recipes, and adapting them for modern palates. Young Diné chefs are returning to their homelands, armed with culinary school training and a passion for their heritage, eager to elevate Diné cuisine onto a broader stage. They are crafting menus that speak to their identity, blending traditional ingredients with contemporary techniques, and championing a farm-to-table ethos that supports local producers.

In essence, the restaurants of the Navajo Nation are not merely places to eat; they are living testaments to the enduring spirit of the Diné people. They embody a rich cultural heritage, fuel local economies, and serve as vibrant community hubs. For anyone traversing the magnificent landscapes of northern Arizona, a stop at a Navajo eatery offers an unforgettable journey – a chance to taste history, tradition, and the hopeful future of a remarkable nation, one delicious, mutton-filled bite at a time. It’s an invitation to connect, to learn, and to savor the unique flavors born from the land and the heart of the Diné.