The rugged, breathtaking expanse of the Navajo Nation, Diné Bikéyah, is more than just land; it is a living repository of history, spirituality, and cultural identity. Across its 27,000 square miles, ancient dwellings cling to canyon walls, towering monoliths pierce the sky, and the very earth whispers stories of creation and survival. These cultural heritage sites are not mere archaeological relics; they are vibrant connections to Diné ancestors, embodying the philosophy of Hózhó, a state of balance and harmony that guides the Navajo way of life.

One of the most profound and accessible windows into this rich heritage is Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Unlike many national parks, Canyon de Chelly is unique because it is entirely owned by the Navajo Nation, co-managed with the National Park Service, and its canyons have been continuously inhabited for over 5,000 years. The sheer sandstone walls, rising hundreds of feet, cradle a verdant canyon floor where Navajo families still farm and raise livestock, maintaining traditions passed down through generations. Within these cliffs are hundreds of Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) cliff dwellings, such as the iconic White House Ruin, accessible via a strenuous trail, or visible from various overlooks along the rim drive. These structures, built between 350 and 1300 AD, tell a story of sophisticated ancient cultures that thrived in this challenging environment.

However, for the Navajo, Canyon de Chelly holds a much deeper spiritual significance. It is a place of emergence, a sacred landscape where heroes journeyed and deities resided. The towering Spider Rock, a sandstone spire reaching 800 feet into the sky, is revered as the home of Spider Woman, a crucial figure in Navajo mythology who taught the Diné the art of weaving and the principles of harmony. "Spider Woman taught us to weave the universe, to connect the strands of life," explains a local Navajo guide, underscoring the spiritual resonance of the landscape. The canyon also bears witness to darker chapters, particularly the devastating "Long Walk" of 1864, when Kit Carson’s troops forced the Navajo from their homes here, a memory etched into the very stones, serving as a powerful reminder of resilience and survival.

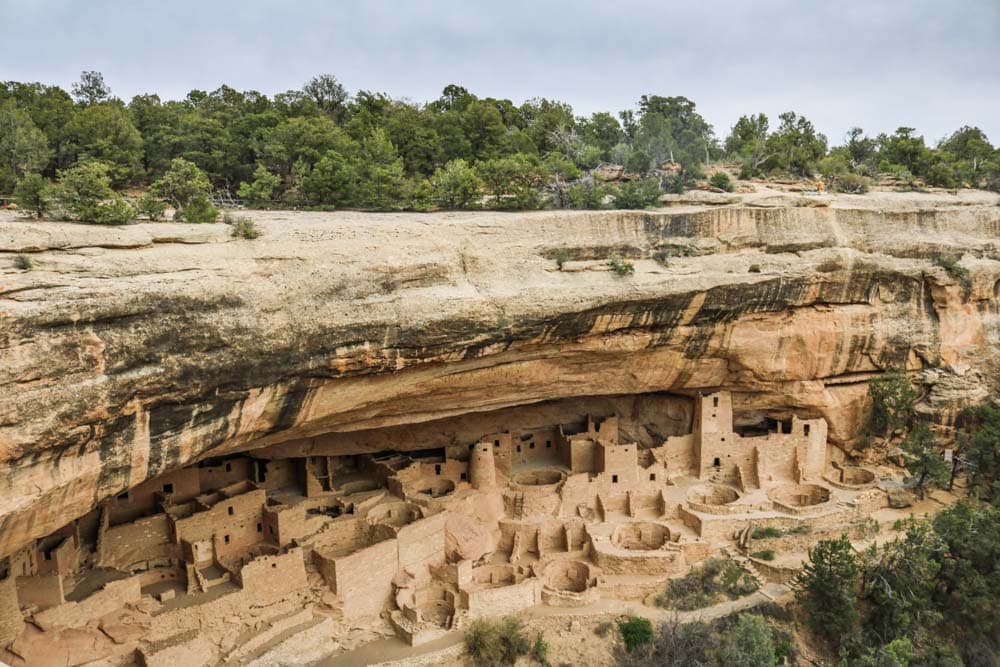

Further north, nestled within remote canyons, lies Navajo National Monument, preserving three of the best-preserved Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings: Betatakin, Keet Seel, and Inscription House. While Inscription House is closed indefinitely for preservation, Betatakin (Navajo for "ledge house") and Keet Seel ("potsherds" in Navajo) offer extraordinary glimpses into the lives of people who built and inhabited these communities between 1250 and 1300 AD. Betatakin, with its 135 rooms, is dramatically set within an alcove, while Keet Seel, the largest of the three with 160 rooms, is even more remote, requiring a permit and a strenuous hike or horseback ride to reach. These sites, though built by Ancestral Puebloans, are fiercely protected by the Navajo Nation, who view them as part of the broader human history of Diné Bikéyah and integral to understanding the complex tapestry of the region. The isolated nature of these monuments has contributed to their remarkable preservation, safeguarding murals, handprints, and other delicate features that connect us directly to their ancient builders.

Perhaps the most globally recognized cultural landscape within the Navajo Nation is Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park. Its majestic sandstone buttes and mesas, sculpted by wind and time, are iconic, instantly recognizable from countless films and photographs. But beyond its cinematic fame, Monument Valley, or Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii ("Valley of the Rocks") in Navajo, is deeply sacred. It is a place of profound spiritual power, where the Diné believe their ancestors walked and where the Earth touches the sky. The formations themselves are often interpreted as figures, protectors, or sacred beings in Navajo cosmology. Driving through the park, one can feel the immense presence of the land, a spiritual weight that transcends mere geology. Local Navajo guides offer tours, sharing not just the geological facts but the oral histories, songs, and prayers connected to each formation, transforming a scenic drive into a deeply immersive cultural experience.

Rising dramatically from the high desert plains, the volcanic neck of Shiprock, or Tsé Bitʼaʼí ("the rock with wings") in Navajo, is another profoundly sacred landmark. This isolated peak, visible for miles in every direction, plays a central role in Navajo creation stories, often associated with the mythical Great Eagle that brought the Diné to their present lands. It is a place of immense spiritual power and reverence, considered too sacred for climbing or extensive visitation. For the Navajo, Shiprock is not just a geological wonder but a living entity, a constant reminder of their origins and their spiritual connection to the land. Its very presence reinforces the idea that the land itself, in its natural forms, is a heritage site.

Beyond these grand, well-known sites, the cultural heritage of the Navajo Nation is woven into the fabric of everyday life. The Hogan, the traditional Navajo dwelling, is a living heritage site. Built according to sacred geometry and oriented to the east to welcome the rising sun, the hogan is more than a house; it is a microcosm of the Navajo universe, a place of ceremony, family, and spiritual connection. Modern hogans, while sometimes incorporating contemporary materials, maintain this traditional structure and spiritual significance. The Window Rock Tribal Park & Veteran’s Memorial, home to the Navajo Nation’s capital, is a contemporary heritage site, commemorating the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II, whose unbreakable code, based on the Navajo language, was instrumental in Allied victory. The site features a striking memorial and the iconic "Window Rock" formation itself, a natural arch that symbolizes the window into the Navajo world.

The preservation of these sites, both ancient and contemporary, is a monumental and ongoing task. The Navajo Nation Historic Preservation Department (NNHPD) plays a crucial role, working to protect archaeological sites, historic buildings, and traditional cultural properties from development, vandalism, and the impacts of climate change. "Our ancestors left us these footprints, these stories etched in stone and land," states a representative from NNHPD. "It is our responsibility, our sacred duty, to ensure they remain for future generations, not just for Diné people, but for all who wish to learn."

Challenges are manifold. Increased tourism, while economically beneficial, puts pressure on fragile sites. Climate change threatens ancient structures with increased erosion and extreme weather. The legacy of resource extraction, particularly uranium mining, has left scars on the land and communities, impacting cultural landscapes and traditional practices. Furthermore, the sheer vastness of Diné Bikéyah means countless uncatalogued sites exist, vulnerable to discovery and disturbance.

Yet, the resolve to protect this heritage is unwavering. The preservation efforts extend beyond physical structures to the intangible heritage of language, oral traditions, ceremonies, and songs. Navajo elders are repositories of vast knowledge, and programs are in place to record and transmit these traditions to younger generations, ensuring that the stories embedded in the landscape continue to be told. The Navajo language itself, Diné Bizaad, is a critical component of this heritage, carrying the nuanced meanings and worldviews that animate the sites. Cultural education initiatives, both within and outside the Nation, strive to foster a deeper understanding and respect for Navajo heritage.

The cultural heritage sites of the Navajo Nation are not static monuments to a bygone era; they are dynamic, living landscapes that embody the enduring spirit of the Diné people. They are classrooms, sanctuaries, and powerful reminders of a profound connection between people and place that has sustained a nation for millennia. Protecting them is not just about preserving rocks and ruins; it is about safeguarding a way of life, a philosophy, and an identity that continues to thrive against all odds, offering invaluable lessons about resilience, harmony, and the sacredness of the natural world.