The Scarred Path Home: Remembering the Navajo Long Walk

The arid landscapes of the American Southwest, with their towering red mesas and vast, silent deserts, hold stories etched not just in stone, but in the collective memory of its oldest inhabitants. Among these, few narratives are as poignant, as harrowing, and ultimately, as testament to indomitable spirit as the Navajo Long Walk – Hwéeldi, as it is known in the Diné language. This forced exodus, a brutal chapter in U.S. history, saw thousands of Diné people driven from their ancestral lands, leaving an indelible scar that continues to shape their identity and resilience today.

The roots of the Long Walk stretch back to the mid-19th century, a tumultuous period defined by America’s insatiable drive for westward expansion and the burgeoning concept of "Manifest Destiny." As settlers encroached upon lands long held by Indigenous peoples, conflicts escalated. For the Diné, a fiercely independent and resourceful nation inhabiting a vast territory across parts of present-day Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, their traditional way of life — centered on farming, sheepherding, and a profound spiritual connection to their land, Dinétah — was perceived as an impediment to progress by the burgeoning American government.

The catalyst for the Long Walk was Brigadier General James H. Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico during the Civil War. While his primary duty was to secure the territory from Confederate incursions, Carleton harbored a secondary, more sinister agenda: to "solve the Indian problem" by removing the Diné and Mescalero Apache from their homelands and confining them to a reservation where they could be "civilized" and converted into farmers. His chosen site was Bosque Redondo, a desolate, windswept tract of land near Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico, hundreds of miles from Dinétah.

To achieve his goal, Carleton enlisted Colonel Kit Carson, a legendary frontiersman known for his skill as a scout and Indian fighter. In 1863, Carson was given explicit orders: wage a total war against the Diné. His directive was uncompromising: destroy their crops, burn their hogans (traditional homes), seize their livestock, and relentlessly pursue any who resisted. "The only possible way," Carleton declared, "is to make them feel the power of the Government." This was not merely a military campaign; it was an act of scorched-earth policy designed to strip the Diné of their very means of survival, leaving them with no choice but to surrender.

Carson’s campaign was brutal and effective. Throughout 1863 and early 1864, his troops systematically devastated Dinétah. They destroyed peach orchards, cornfields, and sheep flocks, driving the Diné to the brink of starvation. Without food, shelter, or livestock, thousands began to surrender, facing the grim reality of forced relocation.

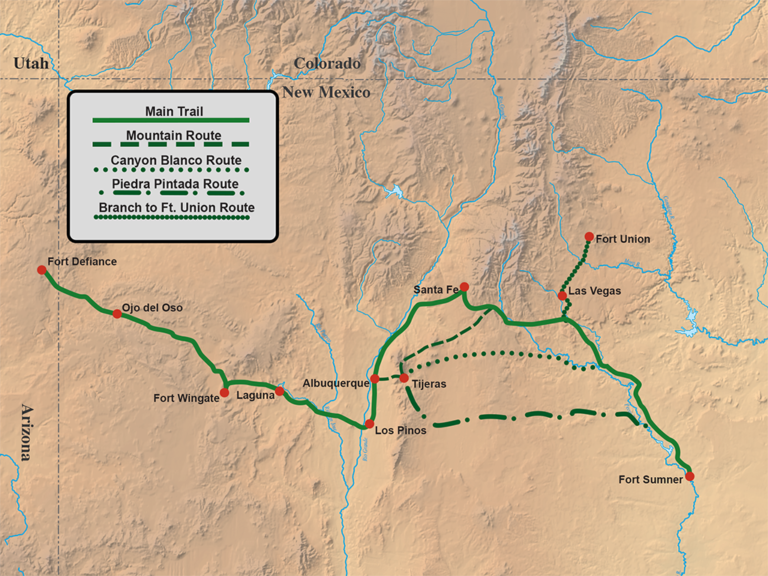

The Long Walk began in earnest in the winter of 1864. Stripped of their possessions, often barefoot and ill-clothed, thousands of Diné – men, women, children, and the elderly – were forced to march under armed guard for hundreds of miles, primarily from Fort Canby (near present-day Window Rock, Arizona) and other points of capture, to Bosque Redondo. The journey was a living nightmare.

"We were driven like sheep," recounted one survivor, as documented in historical records. "Many of us, especially the children and old people, fell by the wayside and died of hunger, thirst, or exhaustion. Their bodies were left unburied, prey for coyotes." The routes, stretching between 300 and 450 miles, traversed harsh terrain, including freezing mountain passes and scorching deserts. Food and water were scarce, often poisoned or unfit for consumption. Disease, particularly smallpox and dysentery, ravaged the weakened captives. Those who faltered or attempted to escape were often shot.

Estimates vary, but it is believed that at least 2,000 to 3,000 Diné, perhaps more, perished during the Long Walk itself, a staggering loss for a population that numbered around 10,000 before the campaign. The memories of this forced march, of loved ones dying and being left behind, are deeply ingrained in Diné oral traditions, passed down through generations as a stark warning and a testament to profound suffering.

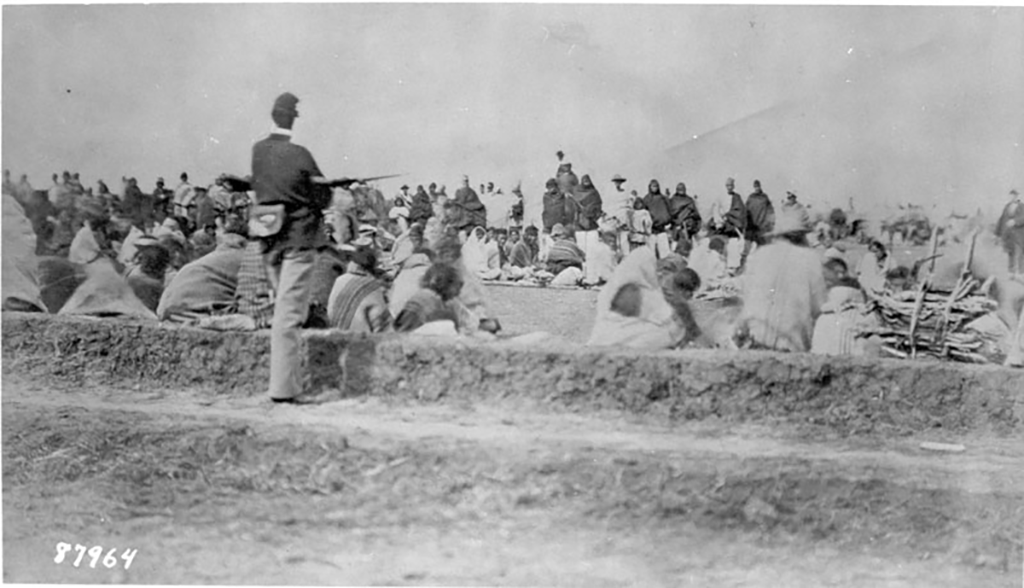

Upon arrival at Bosque Redondo, the ordeal was far from over. The reservation, intended to be a model of "civilization," proved to be a squalid, ill-conceived concentration camp. Between 8,000 and 10,000 Diné, along with a smaller number of Mescalero Apache who had also been forcibly relocated, were confined to an area incapable of sustaining such a large population.

Life at Bosque Redondo was characterized by extreme hardship. The alkaline water from the Pecos River caused widespread illness. The soil was poor, making farming nearly impossible, despite the military’s attempts to force the Diné into an agrarian lifestyle alien to many of their traditions. Firewood was scarce, leading to brutal winters. Rations were meager and often spoiled, leading to starvation and malnutrition. Disease, particularly smallpox, cholera, and dysentery, continued to decimate the population, claiming thousands more lives. The military presence was oppressive, and cultural practices were suppressed. Raids by other tribes, angered by the concentration of so many people on their traditional lands, added to the constant threat.

Carleton’s grand experiment was a catastrophic failure. His vision of transforming independent Diné into docile farmers evaporated in the face of environmental realities and the sheer inhumanity of the conditions. By 1867, it was clear to even the most ardent proponents of the reservation system that Bosque Redondo was unsustainable. The cost of maintaining the fort and feeding thousands of people was astronomical, and the death toll continued to climb.

It was against this backdrop of despair and mounting evidence of failure that the Diné leaders, despite their imprisonment and suffering, began to assert their unwavering desire to return home. Key figures like Barboncito, Manuelito, and Ganado Mucho emerged as powerful voices, articulating the profound spiritual and cultural connection their people had to Dinétah.

Barboncito, in particular, delivered a poignant and unforgettable plea during negotiations with U.S. government commissioners in May 1868. Addressing General William Tecumseh Sherman and Colonel Samuel F. Tappan, he stated: "Our grandfathers lived and died there. Our fathers lived and died there, and we have always lived there. We want to live in our own country, and if you send us away from it, it will be the cause of our death." He emphasized that the Diné would rather die in their own land than live comfortably elsewhere. This powerful articulation of sovereignty and belonging deeply impacted the commissioners.

Recognizing the moral and financial bankruptcy of the Bosque Redondo experiment, the U.S. government finally relented. On June 1, 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo was signed between the Diné leaders and the U.S. government. This was a remarkable and unprecedented achievement: it was the only treaty in U.S. history where a Native American nation, held captive by the military, successfully negotiated its return to its ancestral homeland. The treaty established the Navajo Nation reservation, a smaller but significant portion of their original territory, and provided for livestock, farming tools, and educational opportunities.

The return journey, while still arduous, was imbued with a spirit of hope and liberation. In June and July of 1868, the Diné began their march back to Dinétah. "We are going home!" was the cry that echoed across the plains. Although they returned to a land stripped bare and faced the monumental task of rebuilding their lives from scratch, their spirit was unbroken. They had endured unimaginable suffering and had, through sheer determination and the unwavering strength of their leaders, won back their freedom and their land.

The legacy of the Navajo Long Walk, Hwéeldi, reverberates profoundly through the generations of the Diné people. It is a memory of immense pain and loss, of cultural disruption and the deliberate attempt to erase a way of life. The intergenerational trauma of the Long Walk is still felt today, manifesting in various social and health challenges within the Navajo Nation.

Yet, Hwéeldi is also a powerful testament to resilience, survival, and the enduring strength of Diné identity. It forged a deep collective memory, solidifying their connection to Dinétah and reinforcing the importance of their language, traditions, and sovereignty. The Navajo Nation, now the largest Native American reservation in the United States, with a vibrant culture and a strong sense of self-determination, stands as a living monument to the triumph of the human spirit over oppression.

Remembering the Navajo Long Walk is not just about recounting a historical event; it is about acknowledging the profound injustices committed, understanding the lasting impacts of those actions, and honoring the resilience of a people who faced extermination but chose to walk the scarred path home, carrying their culture and spirit with them. It serves as a crucial lesson for all, reminding us of the human cost of conquest and the enduring power of a people determined to preserve their heritage against all odds.