Manoomin’s Enduring Legacy: The Sacred Harvest of Native American Wild Rice

In the quiet, shimmering waters of the Great Lakes region, where wild rice stalks sway gently in the breeze, lies not just a plant, but a profound story of survival, spirituality, and sustenance. For millennia, Native American tribes, particularly the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Dakota, and Menominee, have revered Manoomin (Ojibwe for "good berry" or "food that grows on water") or Psiη (Dakota) as a sacred gift from the Creator. More than a mere food source, the harvesting of wild rice represents a spiritual endeavor, a cultural touchstone, and an unbroken chain connecting past, present, and future generations. It is a testament to indigenous wisdom, embodying principles of sustainability, reciprocity, and deep ecological respect that are increasingly vital in our modern world.

A Gift from the Creator: The Historical and Spiritual Roots

The history of Manoomin is deeply intertwined with the very identity of the Great Lakes tribes. For the Anishinaabe, the quest for "the food that grows on water" is central to their migration stories, particularly the Seventh Fire Prophecy, which guided them westward from the Atlantic coast to the Great Lakes. This prophecy foretold a time of great challenge and a promise of renewal, urging the people to seek a land where this sacred grain flourished. Upon finding it, they settled, recognizing Manoomin as a cornerstone of their existence.

"Manoomin isn’t just a plant; it’s our relative," explains a contemporary Anishinaabe elder. "It teaches us how to live. It reminds us of our responsibilities to the water, to the land, and to each other." This sentiment underscores a fundamental truth: wild rice is not simply a commodity to be exploited, but a living entity deserving of respect and protection. Its presence signifies healthy waters and a thriving ecosystem, acting as a crucial indicator of environmental well-being.

Unlike domesticated grains, wild rice (Zizania palustris being the most common species in the region) has retained its wild nature, growing exclusively in shallow, clear, slow-moving water. It stands tall, sometimes reaching ten feet, its delicate grains ripening in late summer and early fall, signaling the time for the annual sacred harvest.

The Art of the Sacred Harvest: A Dance with Nature

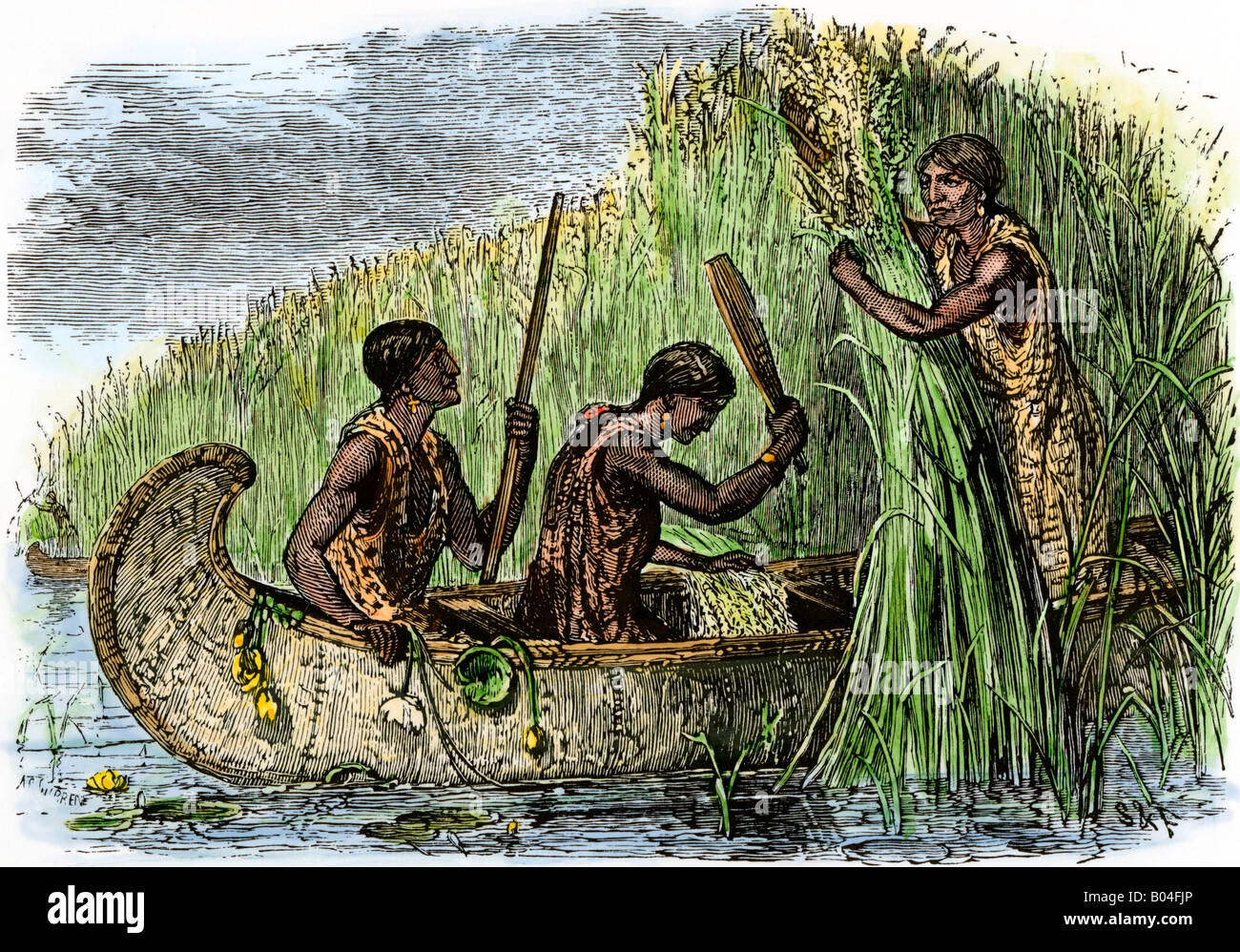

The traditional harvesting of Manoomin is an art form passed down through generations, a gentle dance performed in harmony with nature’s rhythm. It begins in late August or early September, when the rice grains have matured. Harvesters venture onto the water in canoes, often with two people: one to pole the canoe through the dense rice beds, and the other to gather the grain.

The gathering method is both simple and ingenious. Using two cedar knocking sticks, or manoominikaanag, the harvester gently bends the ripe rice stalks over the canoe. With a soft tap, the mature grains are dislodged, falling into the bottom of the canoe. The beauty of this method lies in its sustainability: only the ripest grains, those ready to fall naturally, are gathered. The remaining, less mature grains are left on the stalk to continue ripening and, crucially, to reseed the bed for future harvests. This ensures the long-term viability of the wild rice stands, a practice that stands in stark contrast to destructive industrial harvesting techniques.

"We don’t ‘take’ the rice; we ‘receive’ it," says another elder, emphasizing the spirit of gratitude and reciprocity. "We leave enough for the ducks, for the muskrats, and for the next year’s crop. It’s a teaching about sharing and not being greedy." This community-centered approach ensures that the harvest is a collective effort, often involving families and entire communities working together, strengthening social bonds and transmitting cultural knowledge. The sounds of knocking sticks, laughter, and splashes echo across the water, creating a timeless soundtrack to this annual ritual.

From Water to Plate: A Traditional Food Staple

Once gathered, the raw wild rice undergoes a meticulous multi-step traditional processing method that transforms it into the nutty, chewy grain we recognize. This process, too, is steeped in tradition and community effort.

- Parching: The raw grains are gently roasted, traditionally over an open fire in large kettles. This dries the rice, prevents spoilage, and helps separate the hull from the grain. The unique smoky flavor of traditionally parched wild rice is a hallmark.

- Threshing (Jigging): After parching, the rice is "jigged" or "danced" upon. Historically, this involved placing the rice in a lined pit and treading on it with soft moccasins to loosen the hulls. Today, mechanical hullers might be used, but the principle remains the same.

- Winnowing: Finally, the rice is "winnowed"—tossed in a birch bark tray or winnowing basket, allowing the wind to carry away the lighter chaff, leaving behind the clean, edible grains.

The resulting wild rice is a nutritional powerhouse. High in protein, fiber, and essential minerals like phosphorus, potassium, and zinc, it offers a complete protein source and complex carbohydrates, making it an incredibly healthy and satiating food. Traditionally, it was incorporated into stews, mixed with berries and maple syrup, served as a side dish, or ground into flour for bread. Its versatility and nutritional density were critical for survival in the harsh northern climates, reinforcing its status as Manoomin, the "good berry."

The Spiritual Tapestry of Manoomin

Beyond its practical role as food, wild rice embodies a profound spiritual connection for indigenous peoples. The harvest is often preceded by ceremonies, prayers, and offerings of tobacco, acknowledging the spirit of the rice and seeking permission to gather. It is a time of reflection, thanksgiving, and reconnection with the land and ancestors.

The wild rice beds themselves are sacred spaces. They are seen as living churches, where the lessons of patience, humility, and interdependence are learned. The slow, deliberate pace of the harvest fosters mindfulness and respect for the natural world. Elders teach that Manoomin is not just food for the body, but also food for the spirit, nourishing cultural identity and reinforcing traditional values. It reminds people of their inherent responsibility as stewards of the land and water, a role passed down through countless generations.

Modern Challenges and Threats to a Sacred Harvest

Despite its deep roots and enduring significance, Manoomin and its traditional harvest face numerous threats in the 21st century.

One of the most pressing concerns is habitat degradation and loss. Pollution from industrial and agricultural runoff contaminates the shallow waters where wild rice thrives, while shoreline development destroys crucial habitats. Changing land use patterns and water management practices, such as damming and dredging, alter water levels and flow, making it difficult for wild rice to grow.

Climate change poses an existential threat. Rising water temperatures, increased frequency of extreme weather events (floods and droughts), and altered precipitation patterns disrupt the delicate balance required for wild rice to flourish. Warmer waters can also lead to an increase in invasive species that outcompete native wild rice.

Commercialization and industrial harvesting also present significant challenges. Large-scale mechanical harvesting, often employed for cultivated wild rice (which is a different species or hybrid often grown in paddies), can damage natural wild rice beds and disrupt the ecosystem. The genetic integrity of wild rice is also a concern, with potential threats from hybridization with cultivated varieties or, though less common, genetic modification.

Furthermore, issues of land access and sovereignty often limit tribal nations’ ability to protect and harvest wild rice on traditional territories that are now privately owned or subject to state and federal regulations. This impinges upon treaty rights and cultural practices.

Guardians of the Grain: Preservation and Revitalization Efforts

In the face of these formidable challenges, Native American tribes are leading robust and innovative efforts to protect Manoomin and revitalize its sacred harvest. These initiatives are multifaceted, encompassing ecological restoration, legal advocacy, cultural education, and food sovereignty.

Tribal nations are actively engaged in monitoring water quality, restoring wild rice beds, and implementing sustainable harvesting practices within their territories. They work to remove invasive species, educate local communities about the importance of clean water, and advocate for stricter environmental regulations to protect aquatic ecosystems. Organizations like the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) play a crucial role in co-managing resources and asserting treaty rights.

Legal battles are ongoing to defend treaty-guaranteed harvesting rights and to hold polluters accountable. For example, some tribes have pursued "Rights of Nature" legal strategies, granting legal personhood to wild rice beds, allowing them to be defended in court against environmental harm.

Cultural revitalization programs are paramount. Elders and knowledge keepers are actively teaching younger generations the traditional ways of harvesting, processing, and cooking wild rice. These programs ensure that the language, ceremonies, and stories associated with Manoomin are not lost but continue to thrive, strengthening cultural identity and resilience. Initiatives promoting tribal food sovereignty encourage communities to regain control over their food systems, including wild rice, ensuring access to healthy, traditional foods.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

The Native American wild rice harvest is far more than a seasonal activity; it is a living testament to an enduring culture, a profound spiritual connection to the land, and a model of sustainable living. Manoomin, the "food that grows on water," nourishes not only the body but also the spirit and identity of the indigenous peoples who have been its stewards for millennia.

In an era defined by environmental degradation and a disconnect from natural processes, the sacred harvest of wild rice offers invaluable lessons. It teaches us about reciprocity, the importance of living in harmony with nature, and the deep wisdom inherent in traditional ecological knowledge. Protecting Manoomin means protecting an entire ecosystem, a vibrant cultural heritage, and a way of life that holds critical answers for a sustainable future. As the wild rice continues to sway in the waters of the Great Lakes, it stands as a resilient symbol of Native American perseverance, reminding us all of our shared responsibility to honor and protect the gifts of the Creator for generations to come.