Native American Tribal Sovereignty: A Nation-to-Nation Relationship with the Federal Government

The concept of Native American tribal sovereignty is fundamental to understanding the complex and often contentious relationship between Indigenous nations and the United States federal government. Far from being merely ethnic minorities, Native American tribes are recognized as distinct political entities, a status enshrined in law and history as "domestic dependent nations" engaged in a "nation-to-nation" relationship with Washington D.C. This unique political status, however, has been a battleground for centuries, shaped by treaties, Supreme Court rulings, federal policies, and the unwavering resilience of Indigenous peoples.

At its core, tribal sovereignty means the inherent authority of tribes to govern themselves. This includes the right to form their own governments, enact and enforce laws, determine membership, regulate economic activity, manage lands and natural resources, and administer justice within their territories. This authority predates the formation of the United States and was recognized, albeit imperfectly, in early treaties between European powers and later the nascent American republic. These treaties, often broken, nonetheless established a framework of government-to-government interaction that persists today.

A Shifting Legal and Policy Landscape

The legal foundation of tribal sovereignty in the U.S. rests heavily on a series of Supreme Court decisions in the early 19th century, known as the Marshall Trilogy. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall famously described tribes not as foreign nations, but as "domestic dependent nations," establishing their unique political status. The following year, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Marshall affirmed that the Cherokee Nation was a distinct political community with territorial boundaries within which Georgia law had no force. These rulings, while defining a limited form of sovereignty, acknowledged the inherent governmental authority of tribes and laid the groundwork for the federal trust responsibility – the government’s obligation to protect tribal lands, resources, and self-governance.

However, the path of tribal sovereignty has been far from linear. Following the Marshall Trilogy, the federal government embarked on a series of policies designed to dismantle tribal self-governance and assimilate Native Americans. The Allotment Act of 1887 (Dawes Act), for instance, broke up communal tribal lands into individual parcels, selling off "surplus" land to non-Native settlers. This policy was catastrophic, leading to the loss of two-thirds of the remaining tribal land base and severely undermining tribal cohesion and economic viability.

The pendulum began to swing back with the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, which ended allotment, encouraged tribes to adopt written constitutions and elect governments, and somewhat revitalized tribal self-governance. Yet, another destructive period, the Termination Era of the 1950s and 60s, saw Congress unilaterally terminate the federal recognition of over 100 tribes, ending their sovereign status, dissolving their land bases, and cutting off federal services. This policy proved disastrous, leading to immense poverty and social dislocation for the affected tribes, many of whom fought for decades to regain their federal recognition.

The modern era of Self-Determination began in the 1970s, largely spearheaded by President Richard Nixon’s 1970 message to Congress, which repudiated termination and called for a new policy of tribal self-determination. This shift led to landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which allowed tribes to contract with the federal government to administer federal programs and services (like healthcare and education) that would otherwise be provided by federal agencies. This was a critical step in empowering tribes to manage their own affairs and tailor services to their specific cultural needs.

The Pillars of Modern Tribal Sovereignty

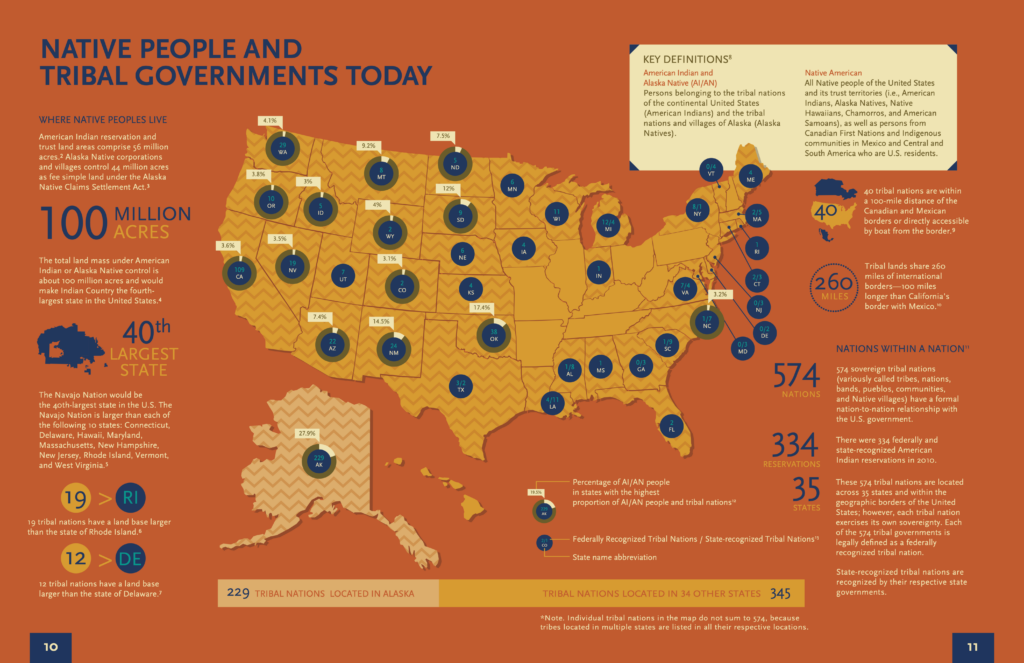

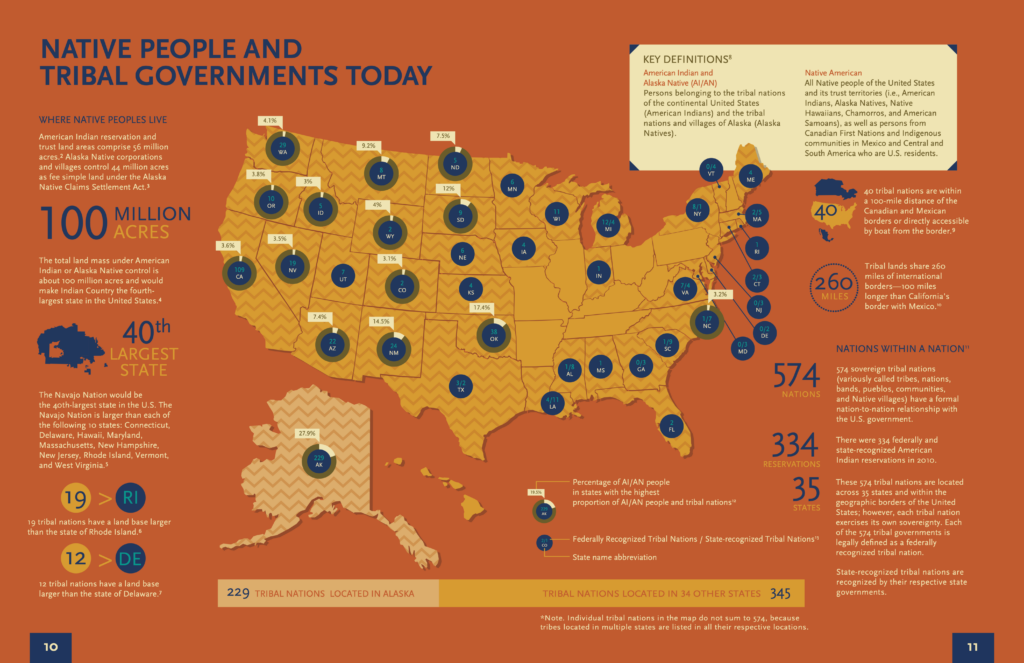

Today, tribal sovereignty manifests in myriad ways, reflecting the diverse needs and aspirations of over 574 federally recognized tribes.

1. Self-Governance and Legal Systems: Tribes operate sophisticated governmental structures, often with written constitutions, elected councils, tribal courts, and law enforcement agencies. These courts handle a wide range of civil and, in many cases, criminal matters involving tribal members within their territories. The ability to create and enforce their own laws is a cornerstone of sovereignty, allowing tribes to maintain cultural practices, protect their citizens, and regulate internal affairs.

2. Economic Development: A crucial aspect of modern sovereignty is economic self-sufficiency. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988 was a transformative piece of legislation, establishing a framework for tribal gaming operations. Tribal casinos have generated billions of dollars, providing essential revenue for tribal governments to fund education, healthcare, infrastructure, and social services, reducing dependence on federal appropriations. Beyond gaming, tribes engage in diverse economic ventures, including energy development, tourism, manufacturing, and resource management, leveraging their unique land base and sovereign status to create jobs and build sustainable economies.

3. Land and Natural Resource Management: Tribes have inherent authority over their trust lands and resources. This includes managing timber, minerals, water rights, and environmental protection. Water rights, often established through historical use or treaty, are particularly vital and frequently contested, as seen in numerous legal battles across the West. Tribes also play a significant role in environmental stewardship, often holding higher environmental standards than surrounding state governments, reflecting a deeply ingrained cultural connection to the land.

4. Cultural Preservation and Social Services: Sovereignty enables tribes to preserve and promote their distinct cultures, languages, and traditions. This includes operating tribal schools that incorporate Indigenous languages and histories, supporting cultural centers, and implementing programs for language revitalization. Furthermore, tribes take on the responsibility of providing healthcare, housing, and social services to their members, often filling gaps left by underfunded federal programs or culturally insensitive state services. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 is another crucial aspect, affirming tribal sovereignty over ancestral remains and cultural items held by museums and federal agencies, mandating their return.

Challenges and the Enduring Fight

Despite significant strides, tribal sovereignty remains a dynamic and often contested concept. The "nation-to-nation" ideal is frequently challenged by jurisdictional complexities, underfunding of federal trust responsibilities, and ongoing battles over land and resources.

Jurisdictional Quagmires: A major hurdle is the often-confusing patchwork of criminal jurisdiction on tribal lands. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978) held that tribal courts do not possess inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Natives, creating a significant public safety gap on many reservations. This means that if a non-Native commits a crime against a Native person on tribal land, tribal police often cannot prosecute the offender, necessitating reliance on under-resourced federal or state authorities. This jurisdictional void has contributed to alarmingly high rates of violence against Native women, a crisis exacerbated by the lack of full tribal authority.

However, recent landmark decisions have also affirmed tribal jurisdiction. In McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), the Supreme Court ruled that a significant portion of eastern Oklahoma, encompassing much of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s historic reservation, remained "Indian Country" for purposes of the Major Crimes Act. This decision, affirming that the reservation was never disestablished by Congress, effectively restored tribal jurisdiction over major crimes committed by Native Americans within these boundaries, marking a monumental victory for tribal sovereignty and the principle of treaty adherence.

Underfunding of Trust Responsibility: The federal government’s trust responsibility often falls short of its obligations. Programs for tribal healthcare (administered by the Indian Health Service), education, housing, and infrastructure are chronically underfunded, leading to significant disparities compared to the general U.S. population. This forces tribes to stretch limited resources or use self-generated revenues to compensate for federal shortfalls, undermining the very premise of the trust relationship.

Resource Exploitation and Environmental Justice: Battles over land and resources continue to pit tribal sovereignty against powerful corporate and governmental interests. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) controversy, involving the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, vividly illustrated this struggle. The tribe asserted its sovereign right to protect its water supply and sacred lands from a pipeline rerouted near its reservation, drawing international attention to issues of environmental justice and the disregard for tribal consultation.

Conclusion: A Resilient Sovereignty

The nation-to-nation relationship between Native American tribes and the U.S. federal government is a testament to the enduring sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. It is a relationship forged in treaties, tested by broken promises, and continually redefined by legal challenges and political advocacy. While the ideal of a true nation-to-nation partnership, based on mutual respect and full recognition of inherent authority, is still a work in progress, the advancements made in self-governance, economic development, and cultural preservation underscore the profound significance of tribal sovereignty.

Native American tribes are not relics of the past but vibrant, modern nations shaping their own futures. Their continued fight for self-determination, the defense of their lands, and the revitalization of their cultures are not merely matters of historical justice but essential components of American democracy and a testament to the inherent right of all peoples to govern themselves. The nation-to-nation relationship, with all its complexities, remains the foundational principle for a just and equitable future for Indigenous peoples within the United States.