The Unseen Borders: Blood Quantum, Lineage, and the Complex Tapestry of Native American Tribal Membership

The concept of citizenship, for most, is a relatively straightforward matter of birthright or naturalization within a nation-state. For Native American tribes, however, membership is a labyrinthine issue, deeply rooted in history, sovereignty, and the ongoing struggle for self-definition. Unlike any other population in the United States, Native Americans navigate a unique dual citizenship – both with the U.S. government and with their own sovereign tribal nations. Central to this complex identity is the question of tribal enrollment criteria, specifically the contentious legacy of "blood quantum" and the evolving landscape of lineal descent.

At its core, tribal membership is not merely a matter of race or ancestry; it is a political relationship, a bond to a distinct sovereign nation. Yet, defining who belongs to these nations has been, and remains, a source of profound internal debate and external pressure. The criteria for enrollment are as diverse as the more than 570 federally recognized tribes themselves, reflecting unique histories, traditions, and political realities. However, two primary methodologies dominate: blood quantum and lineal descent, each carrying its own historical baggage and contemporary challenges.

The Shadow of Blood Quantum: A Colonial Legacy

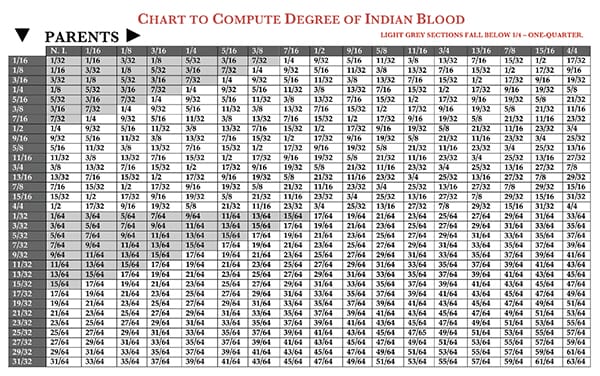

Blood quantum (BQ) refers to the fraction of "Indian blood" an individual possesses, typically expressed as 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and so on. To many, it seems like an innate, traditional measure of identity, but its origins are anything but Native. Blood quantum is a direct imposition of colonial policy, a tool of the U.S. government designed not to preserve Native identity, but to diminish it, to control resources, and ultimately, to assimilate.

The concept gained prominence with the Dawes Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act), which sought to dismantle tribal communal land ownership and parcel out individual plots. To determine who was "Indian enough" to receive an allotment, and conversely, who was "not Indian enough" to be denied tribal status and have their land opened to non-Native settlers, the U.S. government implemented BQ. Federal agents meticulously compiled "blood rolls," often with dubious accuracy, assigning fractional blood amounts based on appearance, hearsay, or self-identification, which could later be used to determine eligibility for federal services or, crucially, for the termination of tribal status.

As Kevin Gover, former Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs and a citizen of the Pawnee Nation, once noted, "The federal government used blood quantum to reduce its obligations to tribes." By defining who was "Indian" through a diminishing fraction, the policy created a demographic ticking time bomb. With each generation, intermarriage between tribal members and non-Natives dilutes the blood quantum, creating a scenario where, theoretically, a tribe could "breed itself out of existence" according to federal definitions, even if cultural identity and community ties remain strong. This insidious aspect of BQ has led some Native scholars and leaders to label it a "paper genocide" – a slow, administrative erasure of indigenous populations.

Tribal Sovereignty and the Adoption of BQ

Despite its colonial origins, many tribes, in exercising their hard-won sovereignty, adopted blood quantum as a component of their own enrollment criteria. This decision was often born out of necessity, a pragmatic response to federal regulations, or a means to solidify their identity and protect their limited resources in a world that constantly sought to undermine their existence.

During the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, which aimed to reverse some of the destructive policies of the Dawes Act and promote tribal self-governance, tribes were encouraged to adopt written constitutions. Many of these constitutions, modeled on federal suggestions, incorporated blood quantum requirements, typically a minimum of 1/4 "Indian blood" from that specific tribe. This threshold became a de facto standard, influencing generations of tribal membership rules.

For tribes establishing new criteria, BQ offered a seemingly objective, albeit flawed, metric to define who belonged. It provided a clear line in the sand, helping to protect tribal land, resources, and cultural practices from further encroachment. However, this adoption also entrenched the very colonial framework that threatened their long-term survival, creating internal divisions and heartbreaking situations where individuals with strong cultural ties are denied membership due to a mathematical fraction.

Lineal Descent: A Growing Alternative

In recognition of the limitations and inherent injustices of blood quantum, many tribes have shifted, or are shifting, towards lineal descent as a primary, or even sole, enrollment criterion. Lineal descent focuses on direct ancestry from an individual listed on an official tribal roll, often an "original enrollee" from a historical census or treaty list, such as the Dawes Rolls or a tribal specific roll compiled during a particular era.

This approach sidesteps the "thinning blood" dilemma of BQ. If an individual can prove direct lineage to an enrolled ancestor, their own "blood quantum" becomes irrelevant. For example, the Cherokee Nation, one of the largest tribes, requires an individual to prove direct lineal descent from an ancestor listed on the Dawes Roll (the final rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes compiled between 1899 and 1907). While the Dawes Roll did record blood quantum for individuals, the Cherokee Nation’s current criteria do not require a minimum blood quantum for new members, only the direct lineage. This allows individuals with even a small fraction of Cherokee ancestry to enroll, as long as the genealogical link is established.

Lineal descent emphasizes the political continuity of the nation, linking current members directly to the historical body politic. It recognizes that tribal membership is about belonging to a specific people and nation, not just possessing a certain percentage of "blood." This shift reflects a move towards self-determination that is less influenced by externally imposed racial classifications and more focused on historical continuity and community bonds.

Beyond the Numbers: Other Criteria and Complexities

While blood quantum and lineal descent are dominant, tribes often incorporate other criteria that reflect their unique cultural values and political structures:

- Community Affiliation/Residency: Some tribes require members to live within a specific geographic area (e.g., the reservation), participate in tribal governance, or demonstrate active engagement in cultural life. This reinforces the idea that membership is about belonging to a living, breathing community, not just a paper identity.

- Language Fluency/Cultural Knowledge: While rarely a primary enrollment criterion due to the impact of forced assimilation on language and culture, some tribes may consider these factors as supplemental or as part of a broader cultural revitalization effort.

- Political Relationship: Ultimately, membership is about one’s political relationship to the tribe. It signifies allegiance and participation in the tribal nation’s life.

The complexities of tribal membership are starkly illustrated in the ongoing issue of disenrollment. In recent decades, a growing number of tribes have disenrolled members, sometimes numbering in the hundreds or thousands. Reasons cited include questioning the validity of ancestral claims, financial motivations (reducing the number of individuals eligible for per capita payments from casino revenues), or political disputes. These decisions, while within the sovereign rights of tribes, are often deeply painful, tearing families apart and leaving individuals feeling stripped of their identity and connection to their ancestral homeland. The disenrollment phenomenon underscores the immense power tribes wield over their own citizenship and the profound emotional weight of belonging.

The Future of Belonging

The debate over enrollment criteria is not merely academic; it is existential. Tribes grapple with the delicate balance of preserving their unique cultural identity and political integrity, while also adapting to modern realities and an increasingly diverse membership base. As intermarriage continues and the concept of "race" evolves, the limitations of blood quantum become ever more apparent.

Many tribal leaders and scholars advocate for criteria that prioritize cultural connection, community engagement, and lineal descent over arbitrary blood fractions. They argue that the strength of a tribal nation lies not just in the "blood" of its people, but in the vitality of its culture, language, traditions, and political self-determination.

The path forward for Native American tribal membership is one of constant negotiation and re-definition. It is a testament to the enduring sovereignty of these nations that they continue to shape their own destiny, defining for themselves who belongs, and how that belonging will be measured, understood, and celebrated for generations to come. The unseen borders of tribal membership are not drawn by arbitrary lines on a map, but by the intricate and deeply personal threads of history, identity, and the unwavering spirit of a people determined to survive and thrive.