The High Stakes Table: Native American Tribal Gaming Compacts, State Negotiations, and the Enduring Fight for Sovereignty

In the sprawling landscape of American commerce, few industries embody such a complex interplay of economics, law, and history as Native American tribal gaming. What began decades ago as modest bingo halls has blossomed into a multi-billion dollar enterprise, fundamentally altering the trajectory of hundreds of tribal nations. At the heart of this transformation lie tribal-state gaming compacts – intricate agreements that dictate the terms under which casino-style gaming can operate on sovereign tribal lands. These compacts are not mere business deals; they are battlegrounds where the inherent sovereignty of tribal nations collides with the regulatory and revenue interests of states, creating a perpetual negotiation over power, self-determination, and economic justice.

The genesis of modern tribal gaming is rooted in a pivotal 1987 Supreme Court decision, California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians. The Court ruled that if a state permitted any form of gambling, it could not prohibit tribes from conducting similar gaming on their reservations. This landmark decision affirmed tribal sovereignty over gaming, but it also signaled the need for a more structured framework. Congress responded swiftly, passing the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) in 1988.

IGRA was designed with a dual purpose: to promote tribal economic development, self-sufficiency, and strong tribal governments, and to regulate Indian gaming to prevent organized crime and ensure fair and honest operation. The Act categorized gaming into three classes. Class I (traditional social gaming) and Class II (bingo, non-banked card games) are largely regulated by tribes themselves, with oversight from the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC). However, Class III gaming – the high-stakes, casino-style operations including slot machines, blackjack, and roulette – requires a tribal-state compact. This is where the complexities begin.

The Negotiation Gauntlet: A Clash of Interests

IGRA mandates that states "negotiate in good faith" with tribes seeking to conduct Class III gaming. This phrase, seemingly straightforward, has been the source of endless litigation and political maneuvering. What constitutes "good faith" from a state often differs dramatically from a tribe’s perspective. States, keen to protect their own lottery and commercial gaming revenues, and to ensure public safety and regulatory oversight, frequently push for concessions that tribes view as infringements on their sovereignty and economic potential.

One of the most contentious issues in compact negotiations is revenue sharing. While IGRA does not explicitly require tribes to share gaming revenues with states, many states demand a portion of the profits in exchange for allowing Class III gaming. Tribes argue that these payments are effectively a tax on their sovereign economic activity, something states cannot levy on other state-sanctioned enterprises. However, states often frame these payments as compensation for infrastructure costs, regulatory burdens, or as a "fair share" for the exclusivity that tribal casinos often enjoy within a given geographic area. For instance, California’s tribal gaming compacts often include significant revenue-sharing provisions, sometimes tying payments to the number of gaming devices or a percentage of net win. In 2022, tribal gaming in California generated over $12 billion, with a substantial portion flowing back to the state in various forms.

Beyond revenue, compacts delve into a myriad of other issues:

- Regulatory Oversight: While tribes have their own sophisticated gaming commissions, states often insist on concurrent jurisdiction or state audit powers, leading to debates over who holds ultimate authority.

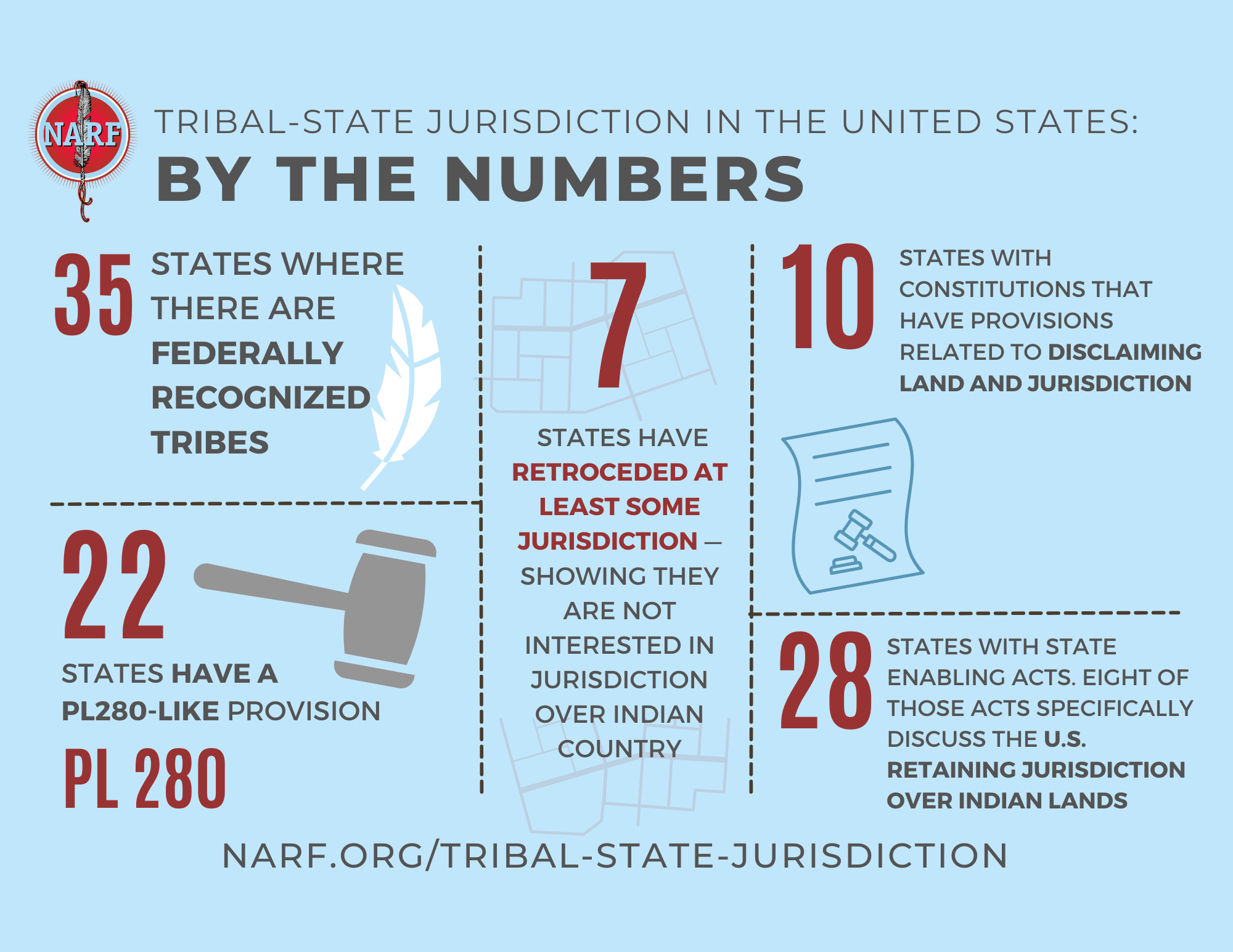

- Jurisdiction: Agreements must delineate jurisdiction over criminal matters, civil disputes, and environmental regulations that arise on or near tribal gaming facilities.

- Labor Relations: Some states attempt to impose state labor laws on tribal enterprises, challenging the tribes’ inherent right to govern employment practices on their lands.

- Exclusivity: States often grant tribes exclusive rights to operate certain types of gaming within a defined region in exchange for higher revenue shares, a trade-off tribes must weigh carefully.

- Siting and Scope: The location of casinos and the types of games offered are also subject to intense negotiation, often influenced by local political dynamics and non-tribal gaming interests.

The negotiation table is rarely level. Tribes, often with limited resources and facing the collective power of a state government, find themselves in a challenging position. The stakes are incredibly high, as the success of these compacts can mean the difference between poverty and prosperity for their communities.

Sovereignty: The Unyielding Foundation

At the bedrock of every tribal-state compact negotiation lies the enduring principle of Native American tribal sovereignty. Tribes are not merely special interest groups; they are distinct political entities with inherent rights of self-governance that predate the formation of the United States. This "government-to-government" relationship is a cornerstone of federal Indian policy, yet it is frequently tested and sometimes undermined during compact talks.

IGRA itself, while recognizing tribal gaming rights, also introduces an element of state control that many tribes view as an intrusion. The requirement for state approval of Class III gaming forces tribes to negotiate with a party that may have conflicting economic interests and a history of encroaching on tribal jurisdiction. "Tribes have always possessed the inherent right to govern themselves and their lands," states Jefferson Keel, former President of the National Congress of American Indians. "Gaming compacts, while necessary under IGRA, often feel like a negotiation for rights we already possess, rather than a true government-to-government discussion."

A critical legal blow to tribal negotiating power came with the 1996 Supreme Court decision in Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida. The Court ruled that the Eleventh Amendment protected states from being sued in federal court for failing to negotiate compacts in good faith. This decision effectively removed a key enforcement mechanism for tribes, leaving them with fewer legal avenues when states refused to negotiate or offered unreasonable terms. While the Department of the Interior can, in some cases, approve Class III gaming procedures if a state fails to compact, this process is lengthy and rarely invoked, further shifting power dynamics toward the states.

For tribes, the compacts are not just about revenue; they are about exercising their sovereign right to economic development and self-determination. Every clause that limits tribal regulatory authority or imposes state jurisdiction is perceived as an erosion of that fundamental right. The ability to control their economic destiny is a vital component of rebuilding nations that have historically faced systemic oppression and economic deprivation.

Economic Revival and the Path to Self-Sufficiency

Despite the arduous negotiation process, the impact of tribal gaming on Native American communities has been transformative. Before IGRA, many reservations faced staggering rates of poverty, unemployment, and inadequate public services. Gaming revenues have provided a lifeline, enabling tribes to invest in critical infrastructure, healthcare, education, and cultural preservation – areas often neglected by federal and state governments.

According to the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC), tribal gaming generated a record $40.9 billion in 2022 across 519 gaming operations owned by 243 tribes. This revenue is not merely distributed to tribal members, although per capita payments do occur in some instances. More significantly, it funds essential governmental services: building hospitals and schools, creating housing programs, developing roads and utilities, and establishing tribal police forces. "Gaming has allowed us to become self-sufficient, to provide for our people in ways we never could before," says a leader from the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, whose California casino is a major economic engine. "It’s about nation-building, not just profit."

Moreover, tribal casinos are significant job creators, employing hundreds of thousands of people, both tribal and non-tribal, often in rural areas with limited economic opportunities. This economic diversification extends beyond the casino floor, with tribes using gaming profits to invest in hotels, resorts, entertainment venues, and other businesses, further strengthening their economies and reducing reliance on a single industry.

The Evolving Landscape and Future Challenges

The world of tribal gaming is not static. As new technologies emerge and market dynamics shift, so too do the challenges and opportunities for tribal-state compacts. The rise of online gaming, for instance, presents a new frontier for negotiation. Tribes, recognizing the potential for new revenue streams, are actively pursuing compact amendments or new agreements to include online sports betting and casino games. This introduces fresh debates over jurisdiction, taxation, and the geographic reach of tribal sovereignty in the digital realm.

Competition from commercial casinos, state lotteries, and other forms of gaming continues to intensify, requiring tribes to be agile and innovative in their operations and negotiations. Furthermore, political shifts within state governments can lead to changes in negotiation stances, sometimes necessitating renegotiation of existing compacts or creating new obstacles.

The struggle for Native American tribal sovereignty in the context of gaming compacts is an ongoing testament to the resilience and determination of tribal nations. These agreements, born from a complex legal framework, are more than just contracts; they are living documents that reflect the delicate balance between federal Indian law, state interests, and the inherent rights of self-governance. As tribal nations continue to leverage gaming for the betterment of their communities, the high-stakes table of negotiation will remain a crucial arena where sovereignty is continually asserted, challenged, and ultimately, defended. The future of tribal gaming compacts will undoubtedly continue to shape the economic landscape of tribal nations and redefine the boundaries of their enduring sovereignty in the American federal system.