Beyond Bloodlines: The Enduring Tapestry of Native American Tribal Clan Systems

At the heart of countless Native American societies, long before the arrival of European settlers, lay intricate and profoundly sophisticated systems of social organization: the tribal clan. Far more than mere genealogical charts, these clan systems served as the foundational blueprints for identity, kinship, governance, and spiritual connection, weaving individuals into a vast, reciprocal web that defined their place in the world. They dictated everything from marriage patterns and land use to ceremonial duties and political alliances, embodying a holistic worldview where family extended beyond immediate relatives to encompass an entire community and, often, the natural world itself.

These systems are not relics of the past; they are living traditions, resilient and adaptable, continuing to shape the lives of Indigenous peoples across North America. Understanding them is crucial to grasping the depth and complexity of Native American cultures and the enduring impact of colonization on their structures.

The Fabric of Kinship: Matrilineal vs. Patrilineal

Clan systems generally fall into two broad categories: matrilineal and patrilineal. In a matrilineal system, descent is traced through the mother’s line. Children belong to their mother’s clan, and identity, property, and often leadership roles are inherited through women. This structure often empowers women with significant social, economic, and political influence, as they are the carriers of the lineage and the keepers of traditional knowledge. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, the Diné (Navajo), and the Hopi are prominent examples of matrilineal societies.

Conversely, in a patrilineal system, descent is traced through the father’s line. Children belong to their father’s clan, and inheritance follows the male lineage. While less common among the more widely documented agricultural tribes, patrilineal systems were prevalent among some Plains tribes and others where hunting or specific male-dominated activities were central to survival. Regardless of the lineage, the core principle of collective identity and mutual responsibility remained paramount.

A universal feature of most clan systems is exogamy, the practice of marrying outside one’s own clan. This rule served several critical functions: it prevented inbreeding, fostered alliances between different clans, and strengthened social cohesion across the entire tribe or confederacy. By marrying into another clan, an individual forged new bonds of kinship and obligation, effectively expanding their social network and reinforcing the interdependencies that sustained the community.

Identity and Belonging: The Personal Sphere

For an individual, clan affiliation was the primary marker of identity. When meeting someone new, the first question was often, "Who are your people? What is your clan?" This question wasn’t idle curiosity; it immediately established a complex web of relationships, responsibilities, and appropriate behaviors. Knowing a person’s clan allowed for the immediate understanding of potential kinship (e.g., "you are my mother’s brother’s clan, so you are like my uncle"), reciprocal duties, and even ceremonial roles.

The clan provided an inherent sense of belonging and a robust social safety net. Every member of a clan was considered family, regardless of biological proximity. This meant that orphaned children were never truly without parents, the elderly were always cared for, and no one was left to face hardship alone. This collective responsibility fostered deep communal bonds and ensured the welfare of all members.

Education and the transmission of cultural knowledge were also deeply intertwined with clan identity. Elders within the clan were responsible for teaching younger generations their history, traditions, spiritual beliefs, and practical skills. This intergenerational learning ensured the continuity of culture and reinforced the importance of one’s place within the larger social fabric.

Governance and Community Organization: The Public Sphere

Beyond personal identity, clan systems were the bedrock of tribal governance and community organization. They provided a structured framework for decision-making, dispute resolution, and resource management.

In many societies, leadership roles were directly tied to specific clans. Among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, for instance, the powerful Clan Mothers held immense authority. They were responsible for nominating, overseeing, and, if necessary, deposing the chiefs (sachems) who sat on the Grand Council. These Clan Mothers, typically the eldest and most respected women of a particular lineage, embodied the matrilineal power structure, ensuring that decisions reflected the long-term well-being of their people and the land. The Great Law of Peace, the foundational constitution of the Haudenosaunee, meticulously outlines the roles of clans and their representatives in maintaining balance and harmony across the Six Nations.

Similarly, the Diné (Navajo), the largest Indigenous nation in the United States, have a complex matrilineal clan system where identity is defined by four clans: "born to" your mother’s clan, "born for" your father’s clan, and then your maternal and paternal grandfathers’ clans. This intricate system creates a vast network of relatives and responsibilities. Historically, clans were crucial in resolving disputes, distributing resources, and maintaining social order within the vast Diné territory. Even today, formal introductions among the Diné include stating one’s four clan affiliations, immediately establishing a web of kinship that transcends modern political boundaries.

Land ownership and resource management were also often clan-based. While the concept of individual private property as understood in European societies was largely absent, clans held collective stewardship over specific territories, hunting grounds, or agricultural plots. This communal approach fostered sustainable practices, as decisions regarding resource use were made with the long-term benefit of the entire clan and future generations in mind.

Phratries, Moieties, and the Spiritual Dimension

To add further layers of complexity and balance, some tribal societies organized their clans into larger groupings called phratries or moieties. Phratries are collections of related clans, often sharing a common ancestral origin or a traditional alliance. Moieties, on the other hand, typically divide an entire tribe or community into two complementary halves, often with specific ceremonial or social functions. For example, one moiety might be responsible for conducting burials, while the other oversees naming ceremonies. These divisions often reflected a desire for balance and reciprocity, ensuring that all aspects of community life were addressed and that no single group held absolute power.

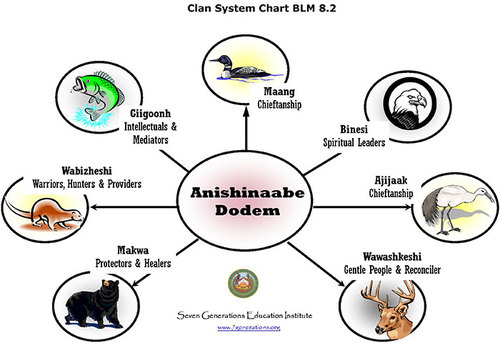

The spiritual dimension of clan systems cannot be overstated. Clans often had sacred animals, plants, or natural phenomena as their totems or symbols, representing their ancestral origins or spiritual protectors. These totems were not merely symbols; they represented a deep spiritual connection to the natural world and a recognition of the interconnectedness of all life. Ceremonial duties, specific rituals, and the guardianship of sacred knowledge were frequently passed down through particular clans, ensuring the proper performance of ceremonies vital for the well-being of the entire community and the maintenance of cosmic balance. The Hopi people, with their numerous matrilineal clans (e.g., Bear, Spider, Water, Sun, Badger), have intricate ceremonial cycles where specific clans are responsible for performing particular rituals essential for rain, harvests, and the continuity of their world.

The Impact of Colonization and Enduring Resilience

The arrival of European settlers and the subsequent policies of colonization launched a relentless assault on Native American clan systems. Colonial governments, driven by a desire to assimilate Indigenous peoples and acquire their lands, actively sought to dismantle these structures. The imposition of individual land ownership through policies like the Dawes Act, the forced removal of children to boarding schools where they were forbidden to speak their languages or practice their cultures, and the establishment of "nuclear family" models all aimed to break down the collective identity and authority inherent in clan systems.

The effects were devastating. Generations experienced cultural trauma, loss of language, and the disruption of traditional governance. Yet, despite immense pressure and overt suppression, many clan systems endured. They adapted, went underground, or continued to function within the confines of imposed colonial structures. The deep-rooted sense of identity and belonging provided by clans proved incredibly resilient, acting as a powerful form of cultural resistance.

Modern Relevance and Revitalization

Today, Native American tribal clan systems are experiencing a powerful revitalization. As Indigenous nations reassert their sovereignty and work to heal from historical trauma, there is a renewed focus on strengthening traditional family structures and governance models. Language immersion programs, cultural education initiatives, and efforts to reclaim ancestral lands all contribute to the resurgence of clan identity and its importance.

For many Native Americans, their clan remains a vital link to their heritage, their community, and their identity in a rapidly changing world. It provides a framework for understanding who they are, where they come from, and their responsibilities to their relatives, their nation, and the land. These systems offer valuable lessons for contemporary society about sustainable living, communal responsibility, and the profound importance of interconnectedness.

The enduring tapestry of Native American tribal clan systems is a testament to the ingenuity, adaptability, and spiritual depth of Indigenous cultures. They are not just historical artifacts but dynamic, living frameworks that continue to nurture identity, strengthen communities, and provide a roadmap for a future rooted in ancestral wisdom. Understanding their complexity is not merely an academic exercise; it is an acknowledgement of the profound and continuing contributions of Native American peoples to the human story.