Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on Native American Treaties: Historical Agreements & Contemporary Implications.

Broken Promises, Enduring Legacy: The Complex Saga of Native American Treaties

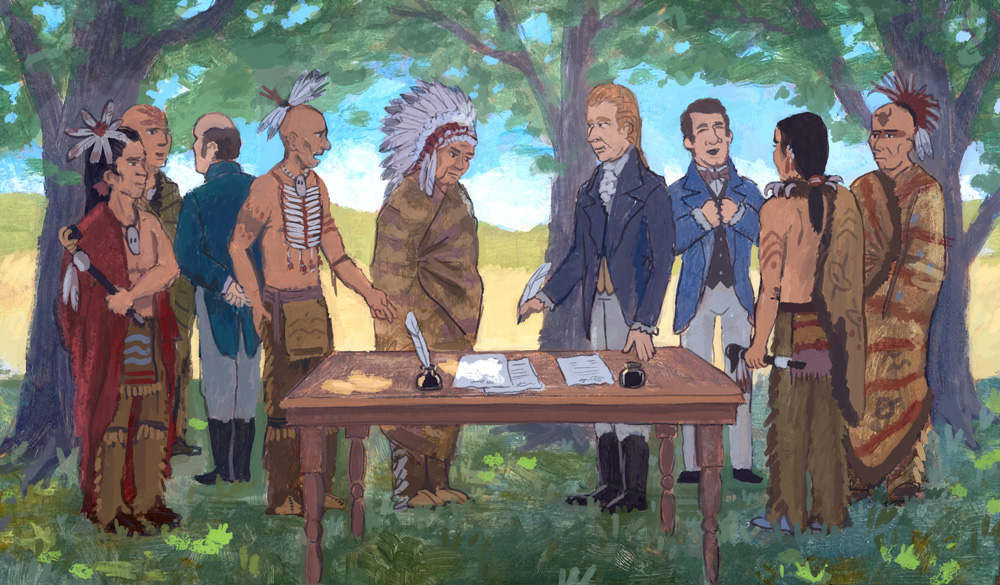

At the heart of the United States’ founding narrative lies a complex, often painful, relationship with its Indigenous peoples. For centuries, this relationship was codified, or at least purported to be, through a series of treaties – formal agreements between sovereign nations. These documents, numbering over 370 ratified by the U.S. Senate, represent both the solemn promises of a nascent republic and the stark reality of its expansionist ambitions. Far from being relics of a distant past, Native American treaties remain profoundly relevant today, shaping legal battles, economic development, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination across Indian Country.

The Era of Treaty Making: A Double-Edged Sword

From the earliest colonial encounters, European powers engaged with Indigenous nations through diplomatic channels, recognizing their sovereignty. The newly formed United States largely continued this practice, viewing treaties as the primary mechanism for acquiring land and securing peace. George Washington, understanding the strategic importance of Native alliances during the Revolutionary War and the need for a stable frontier, advocated for treating tribes as sovereign entities. His administration established a policy of "good faith" negotiations, albeit one often underpinned by coercive power dynamics.

The fundamental disconnect lay in differing worldviews regarding land ownership and sovereignty. For many Indigenous nations, land was communal, a living entity to be stewarded, not bought and sold as private property. European colonizers, conversely, sought individual title and viewed land as a resource for exploitation. Treaties, therefore, often represented a forced compromise, where Native nations ceded vast territories in exchange for guarantees of protection, annuities (payments in goods or money), and the secure, perpetual ownership of their remaining lands – often designated as reservations.

A prime example is the Treaty of Canandaigua (1794), between the United States and the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). It affirmed the sovereign status of the Haudenosaunee and recognized their right to certain lands in New York, which are still held by them today. This treaty, still honored with annual payments of broadcloth, is one of the few that largely endures as intended, a testament to its initial spirit of mutual recognition.

However, as the United States pushed westward, the pretense of good faith often dissolved. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, epitomized this betrayal. Despite a Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) that affirmed Cherokee sovereignty and invalidated Georgia’s claims over their lands, Jackson famously defied the court, stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." This led directly to the forced relocation of the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes along the devastating Trail of Tears, violating numerous treaties and costing thousands of lives.

The mid-19th century saw the peak of treaty making, as the U.S. sought to clear the path for railroads and settler expansion. Treaties like the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851 and 1868) promised vast tracts of land, including the sacred Black Hills, to the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho peoples "as long as the grass shall grow and the water flow." Yet, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills quickly led to its violation, igniting further conflicts and underscoring the U.S. government’s consistent willingness to break its word when resources were at stake.

The Shift to Assimilation: A Legacy of Dispossession

By the late 19th century, the U.S. government’s policy shifted from treaty-making to one of forced assimilation. In 1871, Congress passed an appropriations bill declaring that "no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty." This legislative act effectively ended the treaty-making era, asserting Congress’s plenary power over Native American affairs and relegating tribes to a diminished legal status.

The most devastating policy of this era was the General Allotment Act of 1887 (Dawes Act). Its stated goal was to "civilize" Native Americans by breaking up communal tribal lands into individual plots, encouraging private ownership and farming. The vast "surplus" lands, however, were then opened up to non-Native settlers. This policy was catastrophic: it resulted in the loss of nearly two-thirds of Native American land (approximately 90 million acres) between 1887 and 1934, fragmenting tribal land bases and severely undermining communal traditions and economies. It was, in essence, another form of legal dispossession, cloaked in the guise of progress.

As observed by scholar David E. Wilkins, "The Dawes Act, more than any other single piece of legislation, was responsible for the destruction of Native American land bases and the severe erosion of tribal self-governance."

Contemporary Implications: Enduring Rights and Ongoing Struggles

Despite the historical betrayals and attempts at assimilation, Native American treaties have proven remarkably resilient. They form the bedrock of federal Indian law, defining the unique legal and political relationship between the U.S. government and federally recognized tribes. Today, the implications of these historical agreements are felt across numerous domains:

-

Sovereignty and Self-Determination: Treaties affirmed the inherent sovereignty of Native nations. While Congress’s 1871 act sought to undermine this, the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld a doctrine of "reserved rights," meaning tribes retain all rights not explicitly ceded in treaties or extinguished by Congress. This includes the right to self-governance, to establish their own laws, and to manage their own resources. This fight for self-determination is a constant contemporary battle, from asserting jurisdiction over their lands to determining their own membership and forms of government.

-

Land and Resource Rights: Treaties often reserved specific rights to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded lands, or guaranteed access to water resources. These "usufructuary rights" are frequently the subject of intense legal battles. For example, the Winters Doctrine (1908) established that when reservations were created, tribes implicitly reserved enough water to make their lands livable, a principle that continues to shape water rights disputes across the arid West. The ongoing struggle over the Dakota Access Pipeline, which threatened the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s water supply and sacred sites, highlighted the continuing vulnerability of treaty-protected resources.

-

Economic Development: The recognition of tribal sovereignty has enabled significant economic growth in Indian Country, particularly through gaming. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 recognized tribal governments’ right to operate casinos on reservation lands, often in compacts with states. This has provided crucial revenue for many tribes, funding essential services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure, and reducing reliance on federal aid. However, it also presents challenges, including regulatory complexities and ongoing political pressure.

-

Federal Trust Responsibility: Treaties often included promises of protection and provision, which evolved into the "federal trust responsibility." This is a unique legal and moral obligation of the U.S. government to protect tribal lands, resources, assets, and the general well-being of Native American tribes and individuals. While often underfunded and inconsistently applied, it is a powerful legal principle that tribes invoke to hold the federal government accountable for its commitments, particularly in areas like healthcare, education, and environmental protection.

-

Cultural and Spiritual Preservation: For many Native nations, treaties are more than legal documents; they are living testaments to their identity, history, and spiritual connection to the land. The fight to protect sacred sites, repatriate ancestral remains and cultural objects, and preserve traditional languages and practices often draws strength from the foundational recognition embedded in these historical agreements.

A Path Forward: Reconciliation and True Nation-to-Nation Respect

The legacy of Native American treaties is a stark reminder of the United States’ checkered past, marked by broken promises and systemic injustices. Yet, it is also a testament to the enduring resilience and inherent sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. The ongoing relevance of these agreements means that the conversation is far from over.

As Representative Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), the first Native American Secretary of the Interior, has stated, "The history of Native Americans is a history of broken promises, but it is also a history of incredible resilience and the continuous fight for justice."

Moving forward requires more than just acknowledging historical wrongs. It demands a genuine commitment to honoring treaty obligations, respecting tribal sovereignty as true nation-to-nation relationships, and fostering reconciliation. This includes adequately funding the federal trust responsibility, consulting tribes on decisions affecting their lands and people, and supporting tribal efforts to revitalize their cultures and economies.

The complex tapestry of Native American treaties serves as a powerful reminder that history is not static. These documents, penned centuries ago, continue to shape the present and hold the key to a more just and equitable future for all who share this land. Understanding their enduring implications is not just an academic exercise; it is essential for comprehending the true nature of American democracy and the ongoing journey towards justice and self-determination for its first peoples.