The Enduring Art of Transformation: Native American Hide Tanning Without Modern Chemicals

In an age dominated by industrial processes and synthetic solutions, the ancient art of Native American hide tanning stands as a profound testament to human ingenuity, ecological wisdom, and an intimate connection with the natural world. Far from the chemical-laden vats of modern tanneries, Indigenous peoples across North America perfected methods of transforming raw animal skins into supple, durable, and culturally significant materials using only what the land provided. This sophisticated, labor-intensive process was not merely about creating leather; it was a holistic practice embedded in spiritual reverence, sustainable resource management, and the very fabric of daily survival.

The stark contrast between contemporary tanning and traditional methods could not be more pronounced. Modern industrial tanning, particularly chrome tanning, relies heavily on toxic chemicals like chromium sulfate, which generate significant environmental pollution in wastewater and solid waste. These processes are fast, efficient, and yield uniform products but often come at a steep ecological cost. Traditional Native American tanning, conversely, was a zero-waste endeavor, utilizing every part of the animal and returning all byproducts to the earth in a harmless, often beneficial, way. It represents a masterclass in bio-mimicry, understanding and leveraging natural biochemical reactions to achieve extraordinary results.

Beyond Survival: A Philosophy of Respect and Resourcefulness

For Native American communities, an animal hide was far more than just skin; it was a gift, a sacrifice that provided sustenance, warmth, and shelter. The tanning process was therefore imbued with a deep sense of respect for the animal spirit and a commitment to honor its sacrifice by utilizing every part and ensuring its transformation into something useful and beautiful. This philosophical foundation underscored every step, from the careful removal of the hide to its final softening.

"Every animal has enough brain to tan its own hide," is an old adage often attributed to Native American wisdom, and it encapsulates the essence of this traditional craft. This seemingly simple statement highlights a fundamental principle: nature provides what is necessary. The brains of many animals, particularly deer, elk, and buffalo, are rich in lecithin, emulsifying fats, and enzymes that are crucial for breaking down the hide’s protein structure, lubricating its fibers, and preventing putrefaction. This braining process is the heart of the traditional tan, a biochemical marvel understood and applied empirically for millennia.

The Initial Preparation: A Meticulous Foundation

The journey from a raw hide to finished leather begins with meticulous preparation, a series of steps designed to clean, preserve, and open the hide’s fibers for the subsequent tanning agents.

1. Skinning and Fleshing: Immediately after an animal was taken, the hide was carefully removed. Precision was paramount to avoid nicks or holes that would compromise the final product. Once off the animal, the hide underwent "fleshing" – the removal of all residual meat, fat, and connective tissue from the inner surface. This was a physically demanding task, often performed with specialized tools. Depending on the region and available materials, fleshing tools could be crafted from sharpened stones, bone, elk antler, or later, metal blades hafted to wooden handles. The goal was to achieve a clean, smooth surface, ensuring even penetration of tanning agents and preventing spoilage.

2. Dehairing: The next critical step was dehairing, a process that varied depending on whether a "hair-on" (for robes, rugs, or winter clothing) or "hair-off" (for buckskin, containers, or summer garments) hide was desired. For hair-off hides, several methods were employed:

- Soaking and Scraping: Hides might be soaked in water, sometimes with wood ash (which creates a mild lye solution), to loosen the hair follicles. Once sufficiently softened, the hair was scraped off using a dull-edged tool, often a bone or a stone.

- "Rotting" for Slip-Hair: In some traditions, particularly for thicker hides like buffalo, the hide might be allowed to "rot" slightly in a moist environment. This process caused the hair to "slip" easily, though it required careful monitoring to prevent damage to the hide itself.

- Bucking with Ash Lye: A more controlled chemical process involved soaking hides in a solution of wood ash lye. The alkalinity of the lye helped to break down the hair follicles and the epidermis, allowing for easy removal of hair and the outer skin layer. This also had a conditioning effect on the hide.

After dehairing, the hide was often thoroughly rinsed and scraped again to remove any remaining epidermal layer, ensuring a clean canvas for the tanning stage.

The Alchemy of the Tan: Brains, Oils, and Natural Magic

With the hide meticulously prepared, the true alchemy of tanning began. While various plant materials (like oak bark for its tannins) were used in some regions for specific purposes, the most widespread and iconic Native American tanning method was "brain tanning."

Brain Tanning: The cleaned, dehaired hide was thoroughly worked with the animal’s own brain matter, which had been pounded into a creamy paste. This paste was rubbed vigorously into both sides of the hide, ensuring deep penetration. Sometimes, the brain paste was diluted with water, and the hide was soaked in the solution. The lecithin and fats in the brain emulsified with the natural oils of the hide, lubricating the fibers and preventing them from hardening when dry. The enzymes present in the brain also played a role in breaking down some of the protein structure, making the hide more pliable.

The brained hide was then often wrung out to remove excess moisture and brain matter. This was a critical step, as efficient wringing helped to drive the brain solution deeper into the fibers. Some traditions also incorporated other animal fats, liver, or even egg yolks into the brain solution to enhance its effectiveness, providing additional lubrication and conditioning.

The Labor of Love: Softening and Stretching

Following the braining process, the hide was still wet and somewhat stiff. The next stage, "softening," was arguably the most physically demanding and time-consuming part of the entire process, essential for achieving the characteristic suppleness of buckskin.

As the hide began to dry, it had to be continuously worked – stretched, pulled, twisted, and rubbed. This mechanical action broke down the microscopic bonds that would otherwise cause the fibers to stiffen and lock together upon drying. Without sufficient softening, a brain-tanned hide would dry into a hard, brittle state, much like rawhide.

Methods for softening varied:

- Stretching Frames: Hides were often laced into sturdy wooden frames and pulled taut. Individuals would then stretch and work the hide by hand, pushing and pulling against the frame.

- Post Working: Hides might be pulled back and forth over a rounded wooden post or a sharpened stake driven into the ground.

- Chewing: For particularly soft and fine buckskin, especially for clothing, the hide might even be chewed by women, whose saliva and the mechanical action of their jaws provided an unparalleled level of softening.

- Roping and Twisting: Hides were twisted into ropes, then untwisted, repeatedly, to break down the fibers.

This relentless working continued until the hide was completely dry and achieved the desired softness and drape. It was a process that demanded immense patience and physical endurance, transforming a rigid membrane into a fabric-like material.

The Final Touch: Smoking for Durability and Distinction

The final step in many traditional tanning processes was smoking. While a brain-tanned and softened hide was already a remarkable material, smoking imparted several crucial benefits:

- Preservation and Water Resistance: The smoke, particularly from punky wood or pine needles, contained creosotes and other compounds that helped to "set" the tan, making the hide more resistant to water and less prone to stiffening if it got wet. It also acted as a natural insect repellent.

- Color and Aesthetic: Smoking gave the hide a beautiful, rich golden-brown hue, varying in intensity depending on the type of wood used and the duration of the smoking. This distinctive color became a hallmark of traditional buckskin.

- Odor: The smoky scent was also characteristic and contributed to the overall sensory experience of the material.

The smoking process typically involved creating a small, enclosed space, often a teepee-like structure or a pit, where the softened hide was suspended over a smoldering fire. The smoke was carefully controlled to ensure even penetration and to avoid scorching the hide. Often, a hide would be smoked on both sides, or "double-smoked," especially for outer garments that needed maximum durability and water resistance.

Tools, Community, and Enduring Legacy

The tools employed in traditional hide tanning were elegant in their simplicity and effectiveness. Beyond the fleshing and scraping tools mentioned earlier, there were stretching frames, various types of mallets for pounding, and simple pits or tents for smoking. These tools were often crafted from natural materials – wood, stone, bone, and sinew – reflecting the self-sufficiency of the communities.

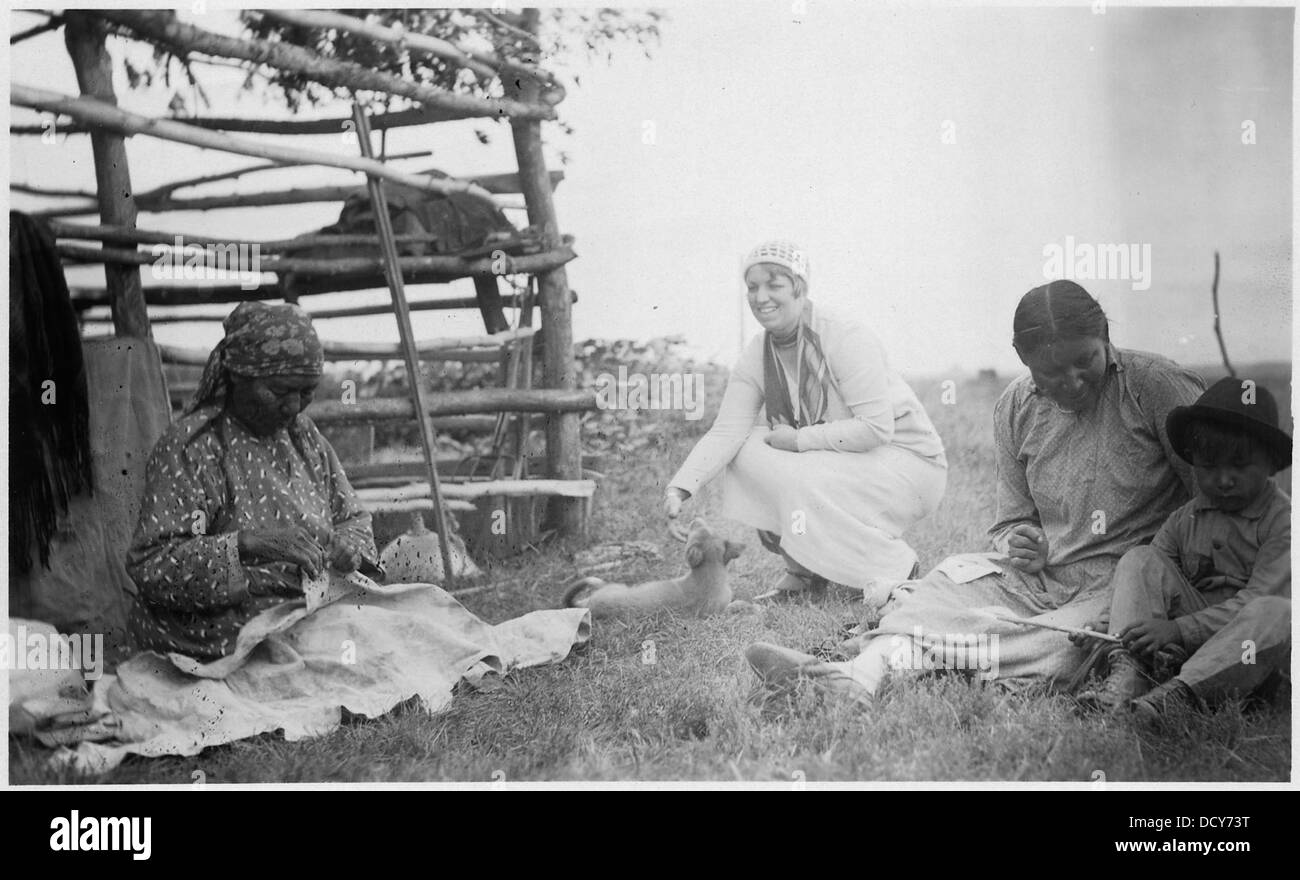

More than individual endeavor, hide tanning was frequently a communal activity. Women, in particular, were often the primary practitioners of this art, passing down knowledge, techniques, and specific tribal variations from generation to generation. The shared labor fostered community bonds and ensured the continuity of this vital skill.

The finished product – buckskin – was incredibly versatile. It was used for clothing, moccasins, tipis and shelters, carrying bags, drumheads, and countless other items essential for daily life. Its breathability, warmth, and quietness made it ideal for hunters, while its durability ensured long-lasting utility.

Lessons from the Past: A Sustainable Future

Today, as concerns about environmental degradation and sustainable living grow, the ancient art of Native American hide tanning offers invaluable lessons. It demonstrates a profound understanding of natural processes, a commitment to zero waste, and a deep respect for the resources provided by the earth. Unlike modern industrial tanning, which creates significant waste streams and relies on non-renewable resources, traditional tanning is biodegradable, energy-efficient, and inherently sustainable.

While the intense labor involved makes widespread commercial adoption challenging, there is a growing movement among Indigenous communities and enthusiasts to revive and preserve these traditional skills. This revival is not just about producing buckskin; it’s about reclaiming cultural heritage, fostering a deeper connection to the land, and demonstrating that sophisticated, high-quality materials can be created without relying on harmful modern chemicals.

Native American hide tanning is more than a historical curiosity; it is a living testament to human ingenuity and a powerful reminder of our capacity to live in harmony with nature. It stands as a timeless example of how deep ecological knowledge, patience, and reverence for life can transform raw materials into enduring necessities, offering wisdom that resonates profoundly in our modern world.