Echoes in Stone: Unveiling the Sacred Imagery of Native American Rock Art

Native American rock art, etched into stone and painted onto cliff faces, stands as an enduring testament to millennia of human presence, belief, and artistic expression across the North American continent. Far from mere decoration, these ancient images are profound cultural documents – spiritual narratives, historical records, and astronomical observations that continue to resonate with power and mystery. To understand this vast legacy, one must delve into the distinct techniques of petroglyphs and pictographs, and the sacred imagery they convey, without the romanticized veil of colonial interpretation, but through the lens of indigenous perspective and archaeological insight.

The terminology itself offers the first distinction: petroglyphs are images carved, incised, or abraded into rock surfaces, while pictographs are paintings applied to rock using mineral pigments. Both forms represent a sophisticated communication system, often found at sites considered sacred, powerful, or significant within the landscape. The sheer scale is staggering; estimates suggest tens of thousands of rock art sites exist across North America, containing millions of individual images, some dating back over 15,000 years, offering a continuous visual chronicle of human thought and interaction with the environment.

Petroglyphs: Carving Messages into Eternity

Petroglyphs, derived from the Greek words "petra" (rock) and "glyphein" (to carve), are created by removing the dark outer layer of rock, known as the desert varnish, to expose the lighter rock underneath. The techniques varied widely, including pecking (striking the rock with a harder stone), incising (scratching lines with a sharp tool), and abrading (grinding the surface smooth). The choice of technique often depended on the type of rock, the desired effect, and the available tools. Hammerstones and chisels, often made of harder stones like quartz or chert, were the primary instruments, wielded by skilled artisans who understood the nuances of the stone canvas.

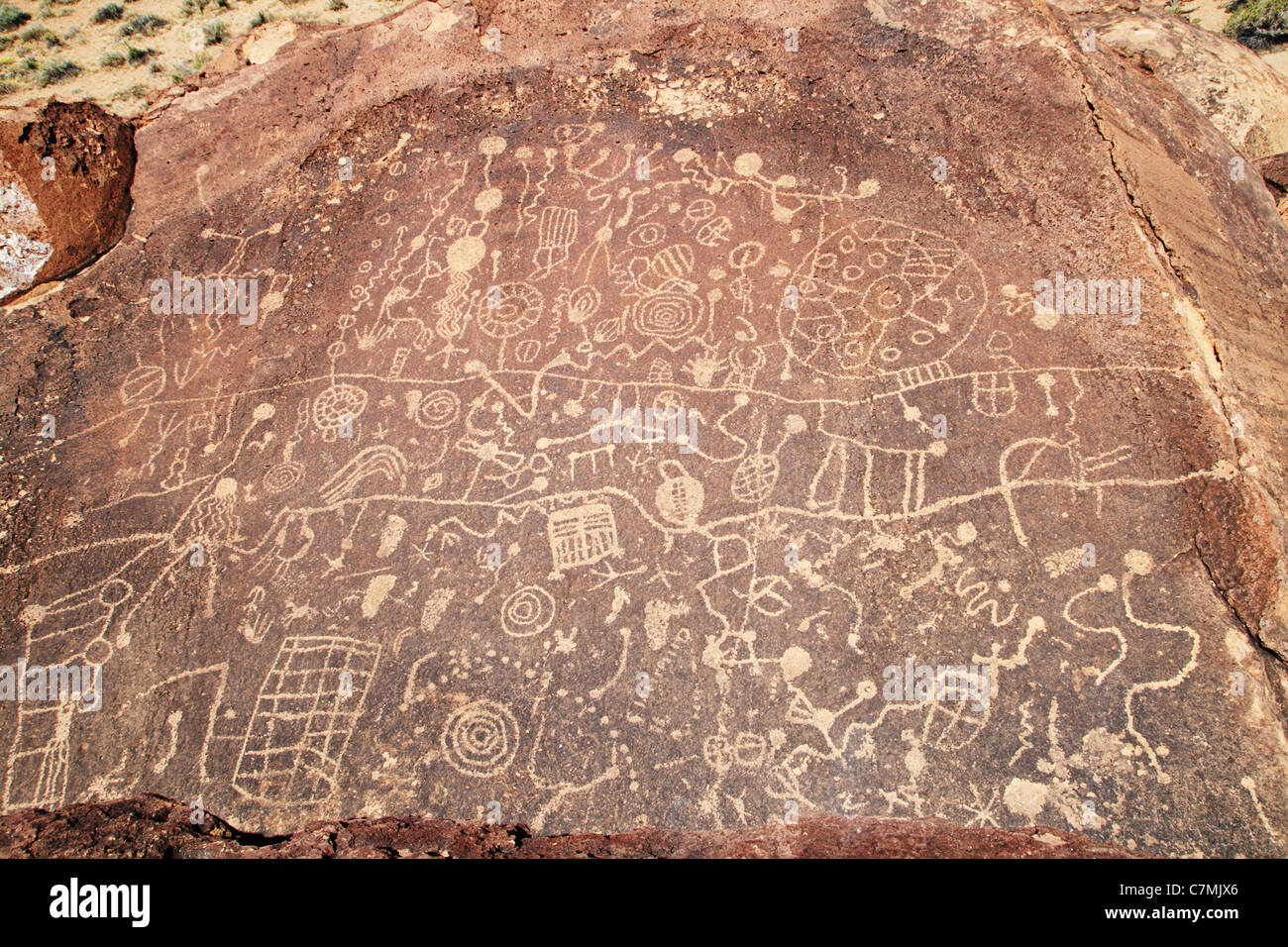

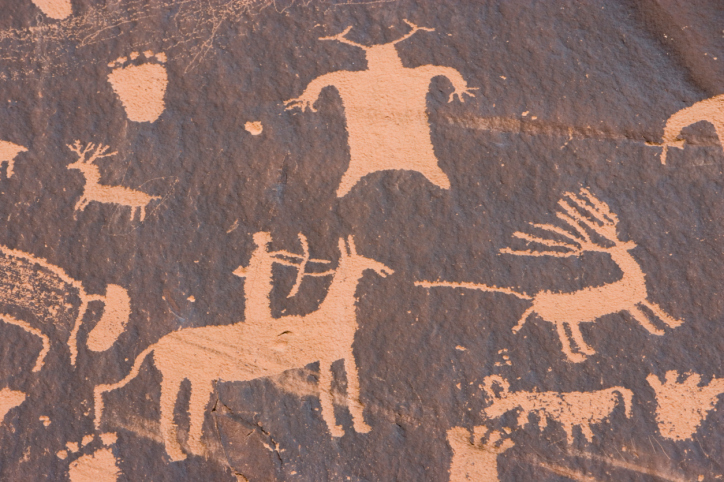

The imagery found in petroglyphs is incredibly diverse, ranging from abstract geometric patterns to highly detailed anthropomorphic (human-like), zoomorphic (animal-like), and composite figures. Common motifs include bighorn sheep, deer, serpents, birds of prey, and human figures often depicted with elaborate headdresses, masks, or holding objects. Handprints and footprints are also frequent, perhaps symbolizing presence, passage, or spiritual connection. Celestial bodies—suns, moons, and stars—are common, often incorporated into intricate designs that hint at astronomical knowledge and observation.

One of the most extensive and well-known concentrations of petroglyphs is found in the Coso Range of California, home to thousands of images, predominantly of bighorn sheep, believed to be associated with hunting magic and ritual. Similarly, Petroglyph National Monument in New Mexico protects an estimated 25,000 images, many attributed to the ancestors of today’s Pueblo people, showcasing a rich tapestry of symbols, including human-like figures, animal tracks, and geometric designs. In Nine Mile Canyon, Utah, often dubbed "the world’s longest art gallery," the Fremont culture left an incredible legacy of petroglyphs and pictographs, including distinct trapezoidal-bodied human figures with elaborate headdresses, alongside a plethora of animal forms.

The permanence of petroglyphs, enduring for millennia, speaks to their profound significance. They were not merely transient sketches but deliberate, time-consuming creations intended to last, communicating across generations and connecting the earthly realm with the spiritual.

Pictographs: Painted Visions on Stone

In contrast to the carved permanence of petroglyphs, pictographs offer a vibrant, albeit often more fragile, window into Native American spiritual and cultural life. These paintings, applied directly to rock surfaces, utilized a palette derived from natural mineral pigments mixed with binders such as animal fat, blood, egg whites, or plant juices. Red was often sourced from hematite or iron oxides, yellow from limonite, white from kaolin or gypsum, and black from charcoal or manganese oxides. These pigments were ground into powders, mixed with binders, and applied using fingers, brushes made from plant fibers or animal hair, or even by blowing paint through hollow bones or reeds to create stenciled effects.

Pictographs often adorn sheltered rock overhangs, caves, and cliff faces, protecting them from the elements, though many have faded or succumbed to erosion over time. Their imagery, like petroglyphs, encompasses a wide spectrum of forms: human figures, animals, mythical beings, and geometric patterns. However, pictographs often possess a more narrative or ceremonial quality, with scenes that appear to depict dances, rituals, battles, or shamanic visions. The use of color adds another layer of symbolic meaning, with specific hues often associated with cardinal directions, elements, or spiritual entities within indigenous cosmologies.

Notable pictograph sites include Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site in Texas, where numerous painted faces and figures by the Jornada Mogollon people adorn the rock shelters, many believed to be related to shamanic practices and water rituals. The Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park in California features intricate and colorful pictographs, some of which are thought to illustrate astronomical events or shamanic journeys. These intricate designs, often depicting complex cosmological scenes, are a testament to the Chumash’s deep understanding of their spiritual world.

Sacred Imagery: Unlocking Ancient Meanings

The true essence of Native American rock art lies in its sacred imagery. These were not casual doodles but deliberate expressions embedded with deep spiritual, ceremonial, and cosmological significance. While the precise meanings of many images are lost to time or remain sacred knowledge held exclusively by specific tribal communities, archaeologists and ethnographers, often working in collaboration with indigenous elders, have developed interpretive frameworks.

One prevalent interpretation centers on shamanism and vision quests. Many figures, particularly the anthropomorphic ones with exaggerated features, elaborate headgear, or composite animal-human forms, are thought to represent shamans in altered states of consciousness, communicating with the spirit world. These images might be visual records of personal visions, spirit guides encountered during quests, or the transformation of the shaman into animal spirits. The Great Basin region, for instance, is rich with abstract and often enigmatic pictographs believed to be related to such shamanic experiences. As Dr. Polly Schaafsma, a leading scholar of Southwestern rock art, notes, "Rock art is inextricably linked to belief systems and ritual practices, offering direct access to the spiritual world of the artists."

Astronomical alignments are another powerful aspect of the sacred imagery. Many rock art sites are meticulously placed to interact with the sun, moon, and stars, marking solstices, equinoxes, and other significant celestial events. The most famous example is perhaps the "Sun Dagger" at Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico. Here, two spirals carved into a cliff face are dramatically bisected by a dagger of light at the summer solstice noon, and flanked by light daggers at the equinoxes, demonstrating an advanced understanding of celestial mechanics and its integration into sacred architecture and art. These sites served as ancient observatories and calendars, guiding agricultural cycles, ceremonial timings, and spiritual renewal.

Beyond shamanism and astronomy, rock art also served as historical and narrative records. Some images depict specific events like battles, migrations, successful hunts, or the arrival of new technologies (e.g., horses introduced by Europeans). Others might convey clan symbols, territorial markers, or instructions for rituals. The narrative quality is particularly evident in some pictograph panels, where sequences of figures appear to tell a story or describe a complex ceremony.

It is crucial, however, to approach interpretation with humility and respect. Indigenous elders often remind us that many meanings are esoteric, intended only for initiates or specific spiritual leaders, and some are simply not meant for external understanding. "These places are our libraries, our churches," a contemporary Ute elder might say, emphasizing that the art is not merely historical artifact but a living part of their heritage and ongoing spiritual connection to the land.

Geographic Diversity and Regional Styles

The vastness of Native American rock art is further underscored by its incredible geographic and stylistic diversity. The Southwest, home to Ancestral Puebloans, Fremont, Mogollon, and Hohokam cultures, boasts some of the most intricate and well-preserved sites. Here, images like the humpbacked flute player Kokopelli are ubiquitous, symbolizing fertility, joy, and the spirit of music. Kiva murals, while distinct from external rock art, share similar spiritual iconography and demonstrate the continuous artistic tradition.

In the Great Basin, encompassing parts of Nevada, Utah, and California, the art often features highly abstract, geometric designs, as well as human and animal figures that are often slender and elongated, strongly suggesting connections to vision quests and shamanic journeys. The Plateau region often depicts powerful spirit beings and mythological creatures. Along the Pacific Northwest coast, art often features stylized marine animals, spirit figures, and clan crests, reflecting the rich maritime cultures.

Even in regions where extensive rock art is less common, like the Midwest or Eastern Woodlands, isolated sites exist, offering glimpses into localized traditions, often in caves or on large boulders. This pan-continental distribution underscores the fundamental human urge to communicate, to express belief, and to mark sacred spaces through enduring imagery.

Conservation and the Future

Today, Native American rock art faces numerous threats. Natural erosion, while a slow process, gradually degrades the images. More acutely, human impact through vandalism (graffiti, bullet holes), development (mining, roads, tourism infrastructure), and unchecked visitation poses significant dangers. Once damaged, these irreplaceable cultural treasures are often lost forever.

Conservation efforts are ongoing, led by federal agencies like the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management, state park systems, and increasingly, by tribal nations themselves. These efforts involve mapping and documenting sites, stabilizing fragile surfaces, educating the public, and implementing protective measures. Ethical tourism, which emphasizes respectful viewing and adherence to site rules, is crucial for preserving these sites for future generations.

In conclusion, Native American rock art is more than just ancient pictures on rocks; it is a profound and living legacy. These petroglyphs and pictographs are windows into complex cosmologies, sophisticated knowledge systems, and deeply held spiritual beliefs that shaped entire civilizations. They are enduring testaments to human creativity, resilience, and an unbreakable connection to the land. As we continue to study and protect these sacred images, we are not just preserving art; we are safeguarding the voices of the past, allowing them to echo across the millennia, reminding us of the rich spiritual and cultural tapestry that defines the indigenous heritage of North America. Understanding and respecting this art is not merely an academic exercise, but an essential step in acknowledging the profound contributions and continuing presence of Native American cultures.