Unbroken Spirit: Native American Resistance to Forced Assimilation

For centuries, the land now known as the United States has been a crucible of cultures, a stage for both cooperation and profound conflict. At the heart of this enduring struggle lies the relentless effort by various settler governments to assimilate Native American peoples, and the equally persistent, multifaceted resistance mounted by Indigenous nations determined to preserve their identity, sovereignty, and way of life. This was not merely a clash of arms, but a profound battle for the soul, waged across battlefields, in courtrooms, within school walls, and deep in the spiritual heart of communities.

The concept of "forced assimilation" itself is a stark testament to the colonial mindset. It was predicated on the belief that Indigenous cultures were inherently inferior, savage, or incompatible with "civilized" society. The goal was nothing less than the eradication of Native identity, language, religion, and governance, replacing them with Euro-American norms. This policy manifested in a brutal array of tactics, from land dispossession and forced removal to the infamous boarding school system, and later, policies aimed at terminating tribal sovereignty. Yet, against this overwhelming pressure, Native American resistance never truly ceased. It adapted, transformed, and endured, a testament to an unbroken spirit.

The Early Battles: Armed Resistance and Cultural Fortitude

From the earliest encounters, Native nations understood the existential threat posed by encroaching European powers. The initial forms of resistance were often military, defending ancestral lands and ways of life against overwhelming technological and numerical superiority. Leaders like Pontiac of the Odawa, who forged a confederacy of tribes in the 1760s to resist British expansion, and Tecumseh of the Shawnee, who in the early 19th century sought to unite tribes to prevent further land cessions, stand as towering figures of armed defiance. These were not random acts of violence but organized, strategic efforts to maintain sovereignty and prevent the erosion of their cultures.

Even after devastating military defeats, resistance continued in subtler, yet equally powerful forms. The Cherokee Nation, for example, famously adopted elements of settler culture – writing a constitution, developing a syllabary (Sequoyah’s invention), and establishing a newspaper – not as an act of assimilation, but as a strategic maneuver to demonstrate their "civilized" status and thus protect their sovereignty and land rights. This legal and political resistance culminated in the landmark Supreme Court cases of the 1830s, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia, which affirmed tribal sovereignty. Though President Andrew Jackson notoriously defied the rulings, these cases laid crucial groundwork for future legal battles.

The Era of Reservations and the Ghost Dance

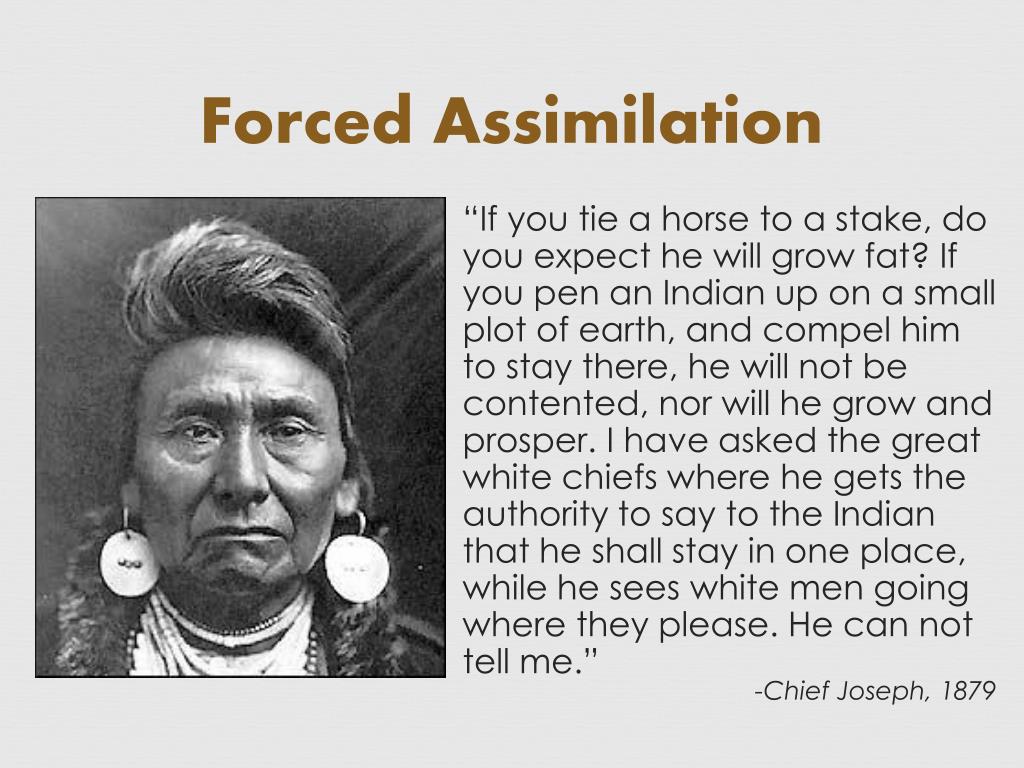

The late 19th century ushered in the reservation era, a period often characterized by immense suffering and intensified assimilation efforts. Confined to often barren lands, stripped of their economic bases, and subjected to federal control, Native peoples faced unprecedented pressure to abandon their traditions. Yet, even here, resistance flourished.

A powerful example of spiritual and cultural resistance emerged in the form of the Ghost Dance movement in the late 1880s. Initiated by the Northern Paiute prophet Wovoka, the Ghost Dance promised a return to traditional ways, the resurrection of ancestors, and the disappearance of the white settlers, all through ceremonial dance and spiritual devotion. It was a movement born of desperation and hope, a profound rejection of the imposed realities and a reaffirmation of Indigenous spiritual power. The U.S. government, viewing it as a dangerous insurrection, responded with brutal force, culminating in the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were killed. Wounded Knee remains a stark reminder of the tragic consequences of assimilation policies and the government’s fear of Indigenous cultural resurgence.

"Kill the Indian, Save the Man": The Boarding School System

Perhaps no instrument of forced assimilation was as insidious and damaging as the Native American boarding school system. Beginning in the late 19th century, thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities and sent to distant boarding schools run by the government or religious organizations. The stated goal, famously articulated by Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was to "Kill the Indian, save the man."

In these institutions, children were stripped of their traditional clothing, had their hair cut, were forbidden to speak their native languages, and were punished for practicing any aspect of their culture. They were indoctrinated in Euro-American religion, values, and vocational skills. The trauma inflicted by these schools – physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; cultural genocide; and the severing of familial bonds – has left deep, intergenerational scars that persist to this day.

Yet, even within these oppressive walls, resistance took many forms. Children found ways to speak their languages in secret, to share stories and cultural knowledge, to form new bonds of kinship. Many ran away, enduring incredible hardships to return home. Survivors of the boarding schools often emerged with an even stronger resolve to preserve their heritage, becoming fierce advocates for their people’s rights. Their very survival and the retention of any cultural knowledge were acts of profound resistance.

The Legal and Political Arena: From Allotment to Self-Determination

Beyond direct military and cultural battles, Native Americans engaged in a sustained legal and political struggle against assimilation. The Dawes Act of 1887, for instance, aimed to break up communally held tribal lands into individual allotments, intending to destroy tribal structures and force Native individuals into an agrarian, capitalist model. This policy resulted in the loss of millions of acres of tribal land to non-Native ownership. However, Native nations and their allies fought back, challenging its implementation and working to regain lost lands and rights.

The mid-20th century saw the "Termination Era," where the U.S. government sought to dissolve tribal governments and end federal responsibility for Native Americans. This, too, met fierce resistance. Tribal leaders, grassroots activists, and emerging inter-tribal organizations mobilized, educated the public, and lobbied Congress, ultimately leading to the rejection of termination and the dawn of the "Self-Determination Era" in the 1970s.

This period witnessed a new wave of overt activism. The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, brought a militant edge to the fight for Native rights, drawing national and international attention to broken treaties, poverty, and systemic injustice. Their occupation of Alcatraz Island (1969-1971), the Trail of Broken Treaties (1972) culminating in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, and the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation, were powerful acts of resistance that forced the nation to confront its historical obligations. These actions, while controversial, undeniably galvanized the movement for tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

Contemporary Resistance: Land, Language, and Identity

In the 21st century, Native American resistance continues, adapting to modern challenges while drawing strength from ancestral traditions. The fight for land and environmental justice remains paramount. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in 2016-2017 became a global symbol of Indigenous environmental activism. Thousands of "water protectors" from across Native nations and around the world gathered to protest the pipeline’s threat to sacred lands and the Missouri River, demonstrating the enduring connection between land, culture, and sovereignty. This movement highlighted the ongoing struggle against resource extraction on Indigenous territories and the persistent disregard for treaty rights and environmental concerns.

Language revitalization efforts are another critical form of contemporary resistance. After generations of suppression, tribes are investing heavily in language immersion schools, master-apprentice programs, and digital resources to ensure their languages, which are repositories of unique worldviews and knowledge, survive and thrive. Every word spoken in a Native language is an act of defiance against assimilation.

Ultimately, Native American resistance to forced assimilation is a story of profound resilience. It is the story of maintaining spiritual practices despite persecution, of speaking ancestral languages in secret, of educating children about their heritage against all odds, and of continuously asserting sovereign rights in the face of ongoing challenges. The unbroken spirit of Native American peoples, forged in centuries of struggle, continues to shape their future, reminding the world that cultural diversity, self-determination, and respect for Indigenous ways of knowing are not just historical footnotes, but vital components of a just and equitable future.