Native American Plant Domestication: How Tribal Farmers Developed Key Food Crops

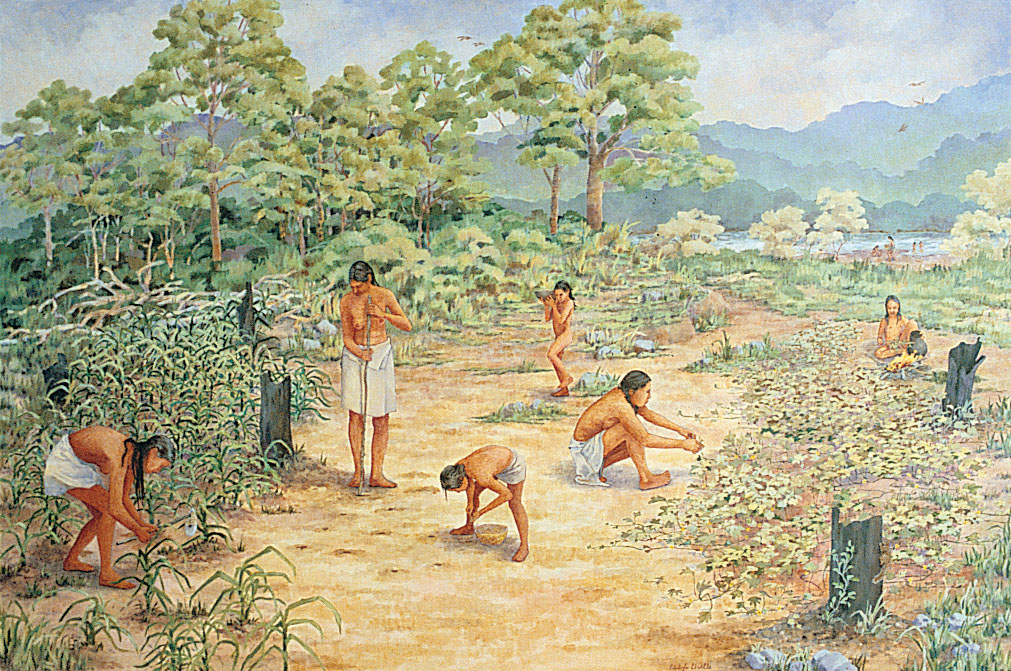

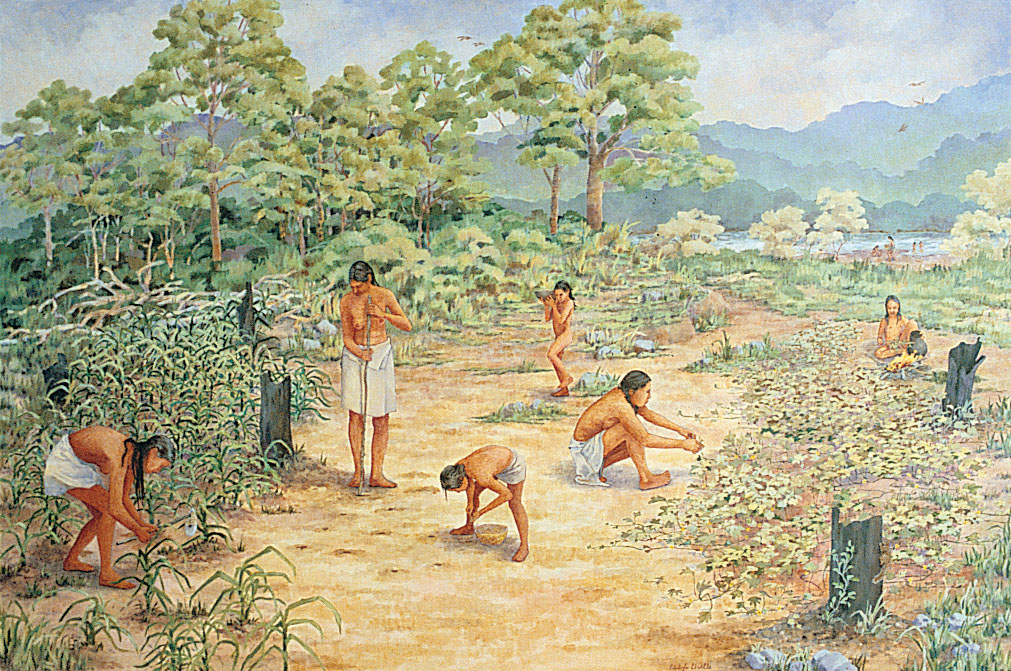

The story of human civilization is inextricably linked to agriculture, a narrative often dominated by the fertile crescents of the Old World. Yet, across the Americas, long before European contact, indigenous peoples were engaged in a revolution of their own – one that transformed wild flora into foundational food crops that now feed billions worldwide. Far from merely foraging, Native American tribal farmers were sophisticated plant geneticists, agronomists, and ecologists, meticulously selecting, cultivating, and enhancing an astonishing array of plants over millennia. Their ingenuity laid the groundwork for many of the most important staples in our global diet, a legacy that is often overlooked but profoundly impactful.

At the heart of this agricultural marvel lies the "Three Sisters" – corn (maize), beans, and squash. This symbiotic trio, a testament to ecological wisdom, represents not just individual crops but an entire farming system. Corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, keeping them off the ground and away from pests. Beans, through nitrogen fixation, enrich the soil, benefiting the nutrient-hungry corn. Squash, with its broad leaves, shades the ground, suppressing weeds and conserving moisture, while its prickly vines deter animal pests. This intercropping strategy maximized yields, maintained soil health, and provided a nutritionally complete diet, showcasing an advanced understanding of plant biology and ecosystem dynamics.

Corn: A Miracle of Domestication

Perhaps the most dramatic example of Native American agricultural prowess is the domestication of corn. Modern maize bears little resemblance to its wild ancestor, teosinte, a grassy plant native to the Balsas River Valley of south-central Mexico. Teosinte has small, hard kernels encased in a tough fruitcase, arranged on a few short spikes. Through an estimated 9,000 years of selective breeding by indigenous farmers, teosinte was transformed into the large-eared, soft-kerneled, nutrient-dense corn we know today. This was not a quick process; it involved identifying and propagating plants with desirable traits – larger kernels, fewer husks, and ears that remained intact after harvest, making them easier to gather and process.

Archaeologist Dr. Bruce Smith, a leading expert on North American plant domestication, once called maize "arguably the greatest human achievement in plant breeding." This transformation required a deep understanding of genetics long before the concept was formally articulated, demonstrating an unparalleled patience and observational skill. From its Mexican origins, maize spread throughout the Americas, adapting to diverse climates and topographies, giving rise to thousands of varieties suited for everything from tortillas to ceremonial uses. Its caloric density made it the engine of civilizations, from the Olmec and Maya to the Inca and countless North American tribes.

Beans and Squash: The Unsung Heroes

While corn often takes center stage, the domestication of beans (Phaseolus species) and squash (Cucurbita species) is equally remarkable. Beans were independently domesticated in multiple locations across the Americas, resulting in a vast array of common beans, lima beans, and runner beans. Early farmers selected for larger, softer beans, easier pod opening, and improved yields. Their role in the Three Sisters system, providing essential protein and nitrogen, made them indispensable.

Squash, particularly Cucurbita pepo, holds the distinction of being one of the earliest domesticated plants in North America, with evidence from the Ocampo Caves in Mexico dating back over 10,000 years. Indigenous peoples developed an astonishing variety of squashes and pumpkins, from hard-shelled gourds used as containers to nutrient-rich winter squashes that could be stored for months, providing sustenance through lean seasons. Summer squashes offered fresh vegetables, while the seeds of many varieties provided healthy fats and proteins. The diversity within these species, nurtured by tribal farmers, highlights their continuous experimentation and adaptation.

Beyond the Three Sisters: A Cornucopia of Crops

The agricultural genius of Native Americans extended far beyond corn, beans, and squash. The global pantry today owes an enormous debt to the indigenous farmers of the Americas for a wealth of other vital crops:

- Potatoes: Originating in the Andes Mountains of South America, the potato (Solanum tuberosum) was domesticated over 10,000 years ago. Andean farmers developed over 4,000 varieties, adapted to high altitudes and diverse microclimates, each with unique flavors, textures, and resistances to pests and diseases. This incredible genetic diversity, painstakingly preserved and cultivated by indigenous communities, became a cornerstone of European and global diets after the Columbian Exchange.

- Tomatoes: Once considered poisonous by Europeans, the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) was domesticated in Mesoamerica from small, cherry-sized wild fruits. Indigenous farmers selected for larger, sweeter, and more colorful varieties, transforming it into the versatile fruit (botanically) that defines countless cuisines today.

- Chilies: The domestication of chili peppers (Capsicum species) began in South America thousands of years ago. From the mild bell pepper to the scorching habanero, indigenous farmers cultivated a vast spectrum of chilies, valued not just for their flavor but also for their medicinal properties and use as food preservatives.

- Sunflowers: Native to Eastern North America, the sunflower (Helianthus annuus) was domesticated by tribal farmers around 3,000 BC. They selected for larger seeds, which were ground into flour, pressed for oil, or eaten as snacks. Along with some squash varieties, sunflowers represent one of the few major crops domesticated north of Mexico.

- Amarnath and Quinoa: These "pseudo-cereals" from Mesoamerica and the Andes, respectively, were staple grains for ancient civilizations like the Aztecs and Incas. Highly nutritious and protein-rich, they are experiencing a resurgence in popularity today as "ancient grains."

- Peanuts, Avocados, Cacao, Vanilla: The list continues, underscoring the profound impact of indigenous agricultural innovation.

The Science and Philosophy of Indigenous Agriculture

The success of Native American plant domestication was not accidental. It was rooted in a sophisticated blend of empirical observation, spiritual connection, and long-term ecological thinking:

- Generational Knowledge: Agricultural practices and seed varieties were passed down through oral traditions, ceremonies, and hands-on learning over countless generations. This cumulative knowledge allowed for continuous refinement and adaptation.

- Biodiversity: Unlike modern industrial agriculture’s monoculture, indigenous farming prioritized genetic diversity. Maintaining a wide array of crop varieties ensured resilience against pests, diseases, and changing environmental conditions. This "insurance policy" is a lesson we are still learning today.

- Holistic Land Management: Indigenous farmers understood their landscapes intimately. They employed techniques like terracing for erosion control, intricate irrigation systems (e.g., the Hohokam canals in Arizona), and controlled burns to manage forests and enhance soil fertility.

- Spiritual Connection: For many Native American cultures, plants were not merely resources but living beings, relatives, and sacred gifts from the Creator. This reverence fostered a sustainable relationship with the land, emphasizing reciprocity and stewardship rather than exploitation. As Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, often articulates, indigenous wisdom teaches that plants "offer us a model of how to be reciprocal, how to live in gratitude."

A Legacy That Feeds the World

The arrival of Europeans in the Americas, often termed the Columbian Exchange, initiated a global redistribution of flora and fauna. While devastating for indigenous populations, it also led to the worldwide adoption of Native American crops. These crops quickly transformed diets and economies across Europe, Africa, and Asia, preventing famines and fueling population growth. Imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes, Irish history without potatoes, or West African stews without chilies – their absence would fundamentally alter global food culture.

Yet, despite this undeniable impact, the scientific and intellectual contributions of Native American farmers have often been marginalized or ignored. Their profound role as innovators, scientists, and stewards of biodiversity deserves prominent recognition. Today, as the world grapples with climate change, food insecurity, and the need for sustainable agricultural practices, the wisdom embedded in indigenous farming systems offers invaluable lessons. Traditional varieties, honed over millennia, possess resilience to drought and pests that modern monocultures often lack. The principles of intercropping, polyculture, and ecological harmony are increasingly seen as vital for building a more sustainable future.

The story of Native American plant domestication is more than just a historical account; it is a living testament to human ingenuity and a powerful reminder of the deep, enduring connection between people and the land. It challenges us to look beyond conventional narratives and acknowledge the profound legacy of tribal farmers whose patient, scientific, and spiritual engagement with the plant world continues to nourish humanity, generation after generation. Their enduring contributions are not merely historical footnotes; they are the very foundation of our global food heritage.