Rekindling Resilience: How Native American Land Management and Fire Practices Offer a Path Forward for a Burning West

As an increasingly volatile climate fuels catastrophic wildfires across North America, a growing chorus of voices is advocating for a return to ancient wisdom: the Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and fire management practices honed over millennia by Native American peoples. For too long dismissed or actively suppressed, these sophisticated land management techniques, particularly the judicious use of prescribed burning, are now recognized as not merely beneficial, but essential for restoring ecological balance, enhancing biodiversity, and protecting communities from the ravages of uncontrolled blazes.

The narrative of "wilderness" as pristine and untouched by human hands is a Eurocentric construct that fundamentally misunderstands the North American landscape. For millennia, Indigenous communities actively shaped their environments through intricate knowledge systems passed down through generations. Fire, far from being a purely destructive force, was a vital tool in this management toolkit. It was used to promote desired plant species, clear underbrush, create habitat for game, facilitate travel, and reduce the risk of large-scale, high-intensity fires. The result was a mosaic landscape – a patchwork of different successional stages – that was inherently resilient and biologically diverse.

Then came the era of colonization. European settlers, observing Indigenous burning, often mislabeled it as "primitive" or "wasteful." Their policies, driven by a fear of fire and a desire to impose their own agricultural and resource extraction models, led to the aggressive suppression of all fires. This "let it burn" mentality, which actually meant "put out every fire," became the dominant paradigm for over a century. The consequences of this misguided policy are now starkly evident: overgrown forests choked with fuel, an accumulation of dead wood and dense undergrowth, and an ecological imbalance that transforms once manageable wildfires into infernos that scorch millions of acres, destroy homes, and endanger lives.

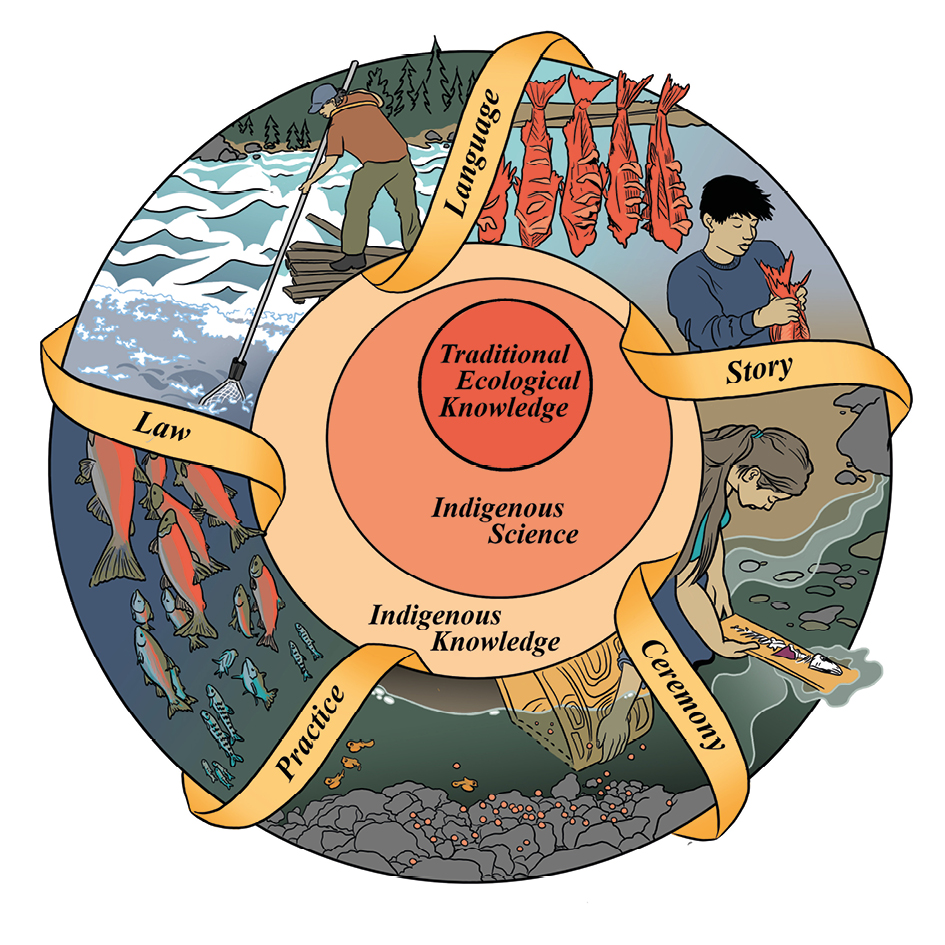

At the heart of Indigenous land management lies Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). This is not merely a collection of facts, but a holistic, adaptive, and culturally embedded understanding of the relationships between living beings and their environment. TEK encompasses a profound awareness of seasonal cycles, plant and animal behavior, soil dynamics, water systems, and the long-term impacts of human actions. Unlike the often reductionist approach of Western science, TEK views the ecosystem as an interconnected web, where humans are an integral part, not separate observers.

"We don’t just see a forest; we see our relatives, our pharmacy, our grocery store," explains a Karuk tribal elder involved in cultural burning initiatives in Northern California. "Fire is not destruction; it’s a cleansing, a renewal, a conversation with the land. It’s how we care for our relatives." This profound spiritual and reciprocal relationship with the land underpins the decision-making process in TEK, leading to management practices that prioritize long-term health and sustainability over short-term gain.

Central to TEK is the understanding and judicious application of fire. Indigenous peoples practiced various forms of burning, each with specific objectives and timings. These "good fires" were typically low-intensity, creeping burns that consumed surface fuels without damaging mature trees. They were conducted at specific times of the year, often in spring or fall, when conditions were optimal – after winter rains but before the peak dry season. The timing was crucial, influenced by factors like wind direction, humidity, fuel moisture, and the life cycles of specific plants and animals.

The benefits of these cultural burns were manifold:

- Fuel Reduction: By regularly clearing underbrush, dead leaves, and fallen branches, Indigenous burning prevented the build-up of excessive fuel loads that now drive megafires.

- Nutrient Cycling: Fire returns nutrients to the soil, promoting new growth and enhancing soil fertility.

- Biodiversity Enhancement: Many native plant species, like certain pines and oaks, rely on fire for seed germination and propagation. Fire also creates diverse habitats, fostering a richer variety of plant and animal life. For instance, the giant sequoias, iconic symbols of California, require fire to open their cones and clear competing vegetation for their seedlings to thrive.

- Pest and Disease Control: Low-intensity fires can help control insect outbreaks and plant diseases by removing infected material and disrupting pest life cycles.

- Water Quality: Healthy, less dense forests with intact understories are better at absorbing and filtering water, reducing runoff and improving water quality.

- Cultural Resource Management: Fire was used to manage food sources like berries and acorns, create open areas for hunting, and maintain access to medicinal plants.

Despite the clear ecological and social benefits, the path to widespread adoption of Indigenous fire practices is fraught with challenges. Historical trauma and mistrust remain significant hurdles. For generations, Indigenous peoples were punished for practicing their cultural burns, their land stolen, and their knowledge devalued. Rebuilding trust requires genuine collaboration, respect for tribal sovereignty, and a commitment to Indigenous leadership in these initiatives.

Bureaucratic and regulatory obstacles also loom large. Strict air quality regulations, liability concerns, and the complex permitting processes for prescribed burns often deter agencies and landowners. The sheer scale of the problem – millions of acres needing treatment – also presents a logistical and financial challenge. There’s a critical shortage of trained personnel, both within tribal nations and mainstream agencies, who possess the necessary expertise to implement these burns safely and effectively.

"The biggest challenge is not the science, it’s the policy and the people," states Dr. Frank Lake, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service and member of the Karuk Tribe. "We have the knowledge, we have the desire, but we need the systemic support to scale up these practices."

Yet, a quiet revolution is underway. Federal and state agencies are increasingly acknowledging the efficacy and necessity of Indigenous fire management. Partnerships between tribal nations and land management agencies are emerging, often led by tribal fire practitioners who are reclaiming their ancestral role as stewards of the land.

In California, tribes like the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa are leading the charge, reintroducing cultural burns on their ancestral lands and demonstrating their effectiveness. The Yurok Tribe’s Cultural Fire Management Council, for example, is actively working with state and federal partners to reduce fuel loads and restore ecological processes in the Klamath River basin, an area historically devastated by wildfires. Their efforts are not just about fire; they’re about revitalizing language, ceremony, and cultural identity.

The Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004, and subsequent amendments, have provided some legal framework for federal agencies to collaborate with tribes on forest management projects that benefit tribal lands. However, many argue that more robust legislation, dedicated funding, and a fundamental shift in land management philosophy are still needed to truly empower tribal nations and integrate TEK on a broader scale.

The implications of embracing Indigenous land management extend far beyond fire suppression. It offers a paradigm shift in our relationship with the natural world, moving from a model of dominance and extraction to one of reciprocity and stewardship. It holds the key to building more resilient landscapes in the face of climate change, protecting critical ecosystems, and ensuring the long-term health of our planet. Moreover, it is an act of reconciliation – acknowledging the historical injustices, valuing Indigenous knowledge, and empowering tribal nations to once again lead in the care of their ancestral lands.

The fires of the past few decades have served as a harsh wake-up call, exposing the failures of a century of fire suppression. As smoke chokes our skies and forests turn to ash, the path forward is illuminated by the wisdom of those who have always lived in harmony with the land. By listening to, learning from, and empowering Native American communities to lead with their Traditional Ecological Knowledge and fire practices, we can begin to heal our landscapes, protect our communities, and rekindle a more sustainable future for all. The question is no longer if we should embrace this ancient wisdom, but how quickly we can integrate it into our collective approach to land stewardship.