Beyond the Podium: Native American Land Acknowledgments as Pathways to Recognition and Reconciliation

In recent years, a quiet but profound shift has been taking place across North America, from university lecture halls to corporate boardrooms, and from national park visitor centers to local community events. It’s the growing practice of Native American Land Acknowledgment – a formal statement recognizing the Indigenous peoples as the original stewards of the land on which an event or gathering is taking place. What might seem like a simple courtesy is, in fact, a complex and evolving practice that sits at the intersection of historical truth-telling, contemporary Indigenous sovereignty, and the arduous journey towards reconciliation.

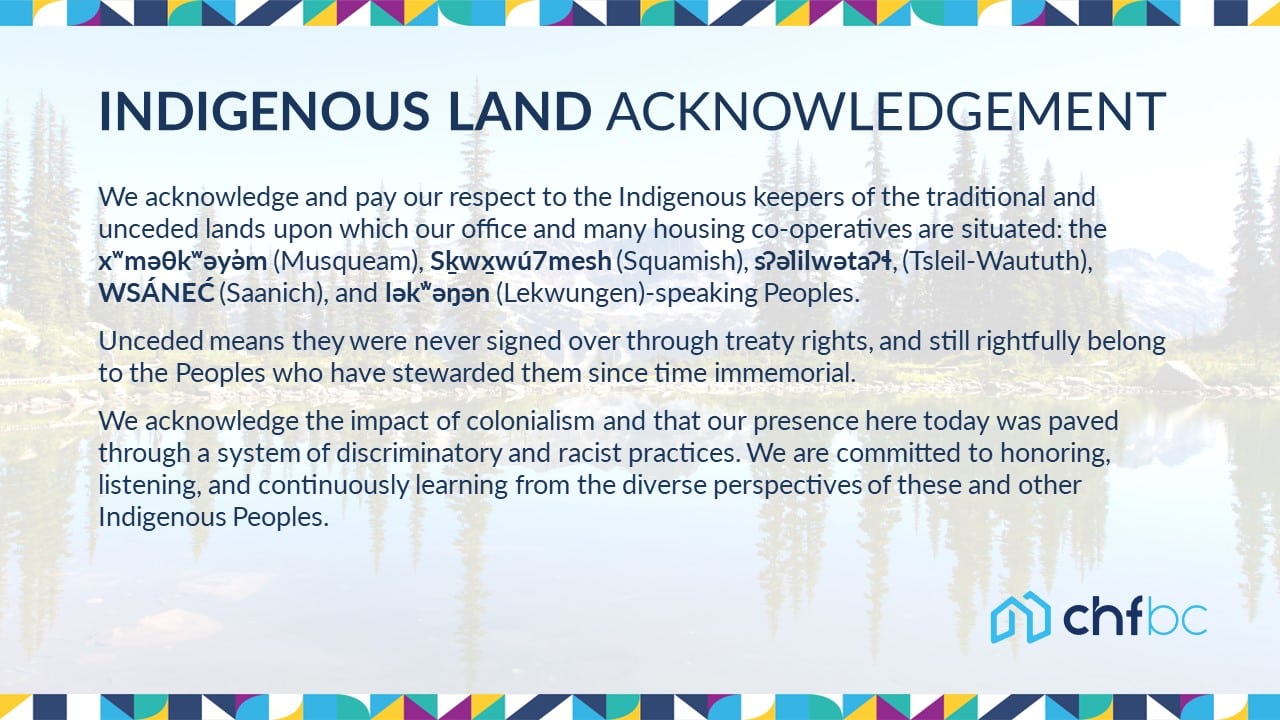

At its core, a land acknowledgment is an invitation to pause, reflect, and confront the often-uncomfortable truths of settler colonialism. It’s a moment to acknowledge that the land we inhabit was, and often still is, Indigenous territory, violently dispossessed and settled without consent. While the practice has roots in countries like Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, where it is often a standard protocol, its adoption in the United States reflects a growing awareness of its own unreckoned history with its First Peoples.

The Weight of History: Why Acknowledgment Matters

To understand the significance of a land acknowledgment, one must first grasp the depth of historical injustice that necessitated it. Before European colonization, North America was home to hundreds of diverse Indigenous nations, each with unique languages, cultures, governance systems, and profound spiritual connections to their ancestral lands. Estimates suggest a pre-contact Indigenous population ranging from 2 million to upwards of 18 million in what is now the United States alone. Their societies were complex, thriving, and sustainable.

The arrival of European settlers ushered in centuries of unparalleled violence, disease, and systematic dispossession. Through mechanisms like the Doctrine of Discovery, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Dawes Act of 1887, and countless broken treaties, Indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their territories, their cultures suppressed, and their populations decimated. Treaties, often signed under duress or outright deception, promised certain lands and rights in perpetuity, only to be systematically violated by the U.S. government. Today, Indigenous nations retain only a fraction of their ancestral lands, often in areas deemed undesirable by settlers, and continue to face systemic challenges stemming from this historical trauma.

"Land is not just property; it is the foundation of our identity, our culture, our spirituality, and our very existence," explains Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy (Hupa, Karuk, Yurok), an Indigenous studies scholar. "When you acknowledge the land, you are acknowledging the people, their history, their resilience, and their ongoing relationship with that place."

For Indigenous peoples, land is more than real estate; it is a living entity, a repository of ancestral knowledge, a source of cultural practice, and the bedrock of their sovereignty. Acknowledging this connection is a vital step in reversing centuries of erasure and recognizing the enduring presence and rights of Indigenous nations.

From Recognition to Reconciliation: The Path Forward

The term "reconciliation" is critical here, as land acknowledgment is intended to be more than a performative gesture. It is a stepping stone, a beginning, not an end. Reconciliation demands concrete action to repair the harms of the past and foster a more just future.

Recognition through acknowledgment involves:

- Truth-Telling: Explicitly naming the Indigenous nations whose ancestral lands are being occupied and acknowledging the historical injustices. This combats the myth of terra nullius (empty land) and the pervasive historical amnesia surrounding Indigenous presence.

- Affirming Sovereignty: Recognizing that Indigenous nations are distinct, self-governing peoples with inherent rights, including the right to their lands and resources as articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), particularly Article 26: "Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired."

- Visible Presence: Making Indigenous peoples visible in spaces where they have often been marginalized or erased, from academic institutions to public monuments.

However, the real power of land acknowledgment lies in its potential to catalyze reconciliation. This requires moving beyond words to tangible commitments. As many Indigenous leaders and scholars emphasize, a land acknowledgment without action risks becoming tokenism, a shallow gesture that merely assuages settler guilt without contributing to meaningful change.

"An acknowledgment is a start, but it’s just the tip of the iceberg," states Fawn Sharp (Quinault), former President of the National Congress of American Indians. "The real work of reconciliation involves returning land, honoring treaties, supporting tribal sovereignty, and investing in Indigenous communities."

Practices for Meaningful Reconciliation Beyond Acknowledgment:

- Financial Support: Directing resources, such as donations or land taxes, to local Indigenous nations or Indigenous-led initiatives.

- Educational Initiatives: Integrating Indigenous history, culture, and contemporary issues into curricula at all levels, taught by Indigenous educators where possible.

- Repatriation and Rematriation: Supporting the return of ancestral remains and cultural items from museums and private collections (repatriation), and the return of land to Indigenous stewardship (rematriation).

- Policy Advocacy: Advocating for policies that uphold treaty rights, protect sacred sites, and support Indigenous self-determination and environmental justice.

- Consultation and Collaboration: Engaging directly with local Indigenous nations on projects, developments, and policies that affect their traditional territories. This includes respecting Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), a key principle in UNDRIP.

- Challenging Narratives: Actively working to dismantle stereotypes and misinformation about Indigenous peoples.

The Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its noble intentions, land acknowledgment is not without its challenges and criticisms.

One primary concern is tokenism or performative allyship. When an acknowledgment is delivered without genuine understanding, research, or follow-through, it can feel hollow and even exploitative to Indigenous communities. It risks becoming a box-ticking exercise, a superficial way for institutions to appear progressive without committing to substantive change.

Another challenge is the burden of emotional labor placed on Indigenous peoples. They are often asked to educate, to validate, and to lead these conversations, sometimes without adequate compensation or recognition for their expertise and experience.

There’s also the question of authenticity and specificity. Generic acknowledgments that don’t name specific nations, acknowledge specific historical harms, or articulate a call to action can be less impactful. Researching which specific nations historically occupied the land, and which nations continue to thrive there today, is crucial. For example, the University of Arizona, a land-grant institution, acknowledges that it is on the traditional homelands of the Tohono O’odham and Pasqua Yaqui peoples, and extends its respect to the 22 federally recognized tribes of Arizona.

Finally, some critics argue that land acknowledgments, while well-intentioned, divert attention from the more urgent and complex work of decolonization – the dismantling of colonial systems and structures that continue to oppress Indigenous peoples. They emphasize that while words are a start, they are meaningless without the tangible transfer of power, land, and resources.

Crafting Meaningful Acknowledgments: Best Practices

For those committed to making land acknowledgment a meaningful practice, several best practices can guide the way:

- Do Your Research: Understand the specific Indigenous nations whose land you are on, their history, their contemporary presence, and their preferred terminology. Resources like Native-Land.ca or local tribal cultural centers can be invaluable.

- Consult (Where Appropriate): If possible and respectful, consult with local Indigenous leaders or cultural experts. This demonstrates genuine respect and ensures accuracy.

- Personalize and Localize: Avoid generic scripts. Make the acknowledgment specific to the place, the event, and the people involved.

- Make it an Ongoing Commitment: Don’t treat it as a one-off statement. Integrate it into the culture of your organization or event.

- Connect to Action: Crucially, link the acknowledgment to concrete actions. What specific steps will your organization take to support Indigenous sovereignty, education, or justice? This might include financial contributions, partnerships, educational programming, or policy advocacy.

- Educate Your Audience: Provide context. Explain why a land acknowledgment is being made and what it signifies for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- Center Indigenous Voices: Ensure that Indigenous perspectives and leadership are central to any reconciliation efforts.

The Future of Land Acknowledgment

The evolution of Native American Land Acknowledgment reflects a broader societal awakening to historical injustices and the urgent need for a more equitable future. It is a powerful tool for education, for raising awareness, and for initiating conversations that have been long overdue.

However, its true impact will not be measured by the number of times it is recited, but by the tangible changes it inspires. It is a call to action for settlers to understand their place in the ongoing history of colonialism and to commit to dismantling its legacies. It is an affirmation of Indigenous resilience, sovereignty, and the enduring connection to their ancestral lands.

As the practice continues to evolve, it serves as a powerful reminder that reconciliation is not a destination but a continuous journey—one that demands honesty, humility, and unwavering commitment to justice. The words spoken in a land acknowledgment are just the beginning; the real work lies in the actions that follow, echoing the promise of a future where Indigenous peoples are not just acknowledged, but truly recognized, respected, and empowered.