The Galloping Revolution: How the Horse Transformed Native American Plains Societies and Traditions

The arrival of the horse on the North American Plains was not merely the introduction of a new animal; it was the ignition of a profound cultural and societal revolution. For centuries, the Indigenous peoples of the vast grasslands had adapted to a challenging environment, their lives intrinsically linked to the immense buffalo herds. But the horse, an animal unknown to them until the 17th century, unleashed an era of unparalleled mobility, power, and prosperity, fundamentally reshaping hunting, warfare, social structures, and spiritual beliefs, creating the iconic "Plains Indian" culture that endures in popular imagination.

The story of the horse’s diffusion across the Plains is a testament to Indigenous ingenuity and adaptation. Spanish conquistadors, venturing north from Mexico in the 1500s, brought horses to the continent, but initially guarded them closely. It was the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when the Pueblo people expelled the Spanish from New Mexico, that scattered thousands of horses across the Southwest. From this point, through trade, capture, and eventually sophisticated breeding, horses spread like wildfire. Tribes like the Utes, Shoshone, and Comanche were among the first to acquire them, quickly becoming masters of horsemanship. Within a century, the horse had reached virtually every major Plains tribe, from the Lakota and Cheyenne in the north to the Apache and Wichita in the south.

Initially, these majestic creatures were referred to by various names, often reflecting their unknown nature, such as "mystery dogs," "big dogs," or "God’s dogs." However, their utility quickly became apparent. Prior to the horse, Plains hunting was a labor-intensive and often dangerous affair. Hunters on foot relied on buffalo jumps, corrals, or surrounds, requiring immense communal effort to drive herds into traps. The success of a hunt was often precarious, and the physical toll immense. The horse, however, transformed this into a dynamic, individual pursuit.

Mounted hunters could ride directly into a stampeding herd, select their target, and dispatch it with arrows or lances with unprecedented efficiency. A single skilled rider could bring down several buffalo in one chase, a feat unimaginable on foot. This increased efficiency meant more meat, more hides, and more bone for tools, leading to a significant improvement in diet and material wealth. The horse not only made hunting easier but also expanded access to resources, allowing tribes to follow the vast, migratory herds across wider territories with greater ease. The Plains became a land of plenty, sustained by the symbiotic relationship between hunter, horse, and buffalo.

Beyond hunting, the horse revolutionized warfare and inter-tribal relations. Before horses, conflicts were typically fought on foot, characterized by ambushes and limited mobility. With horses, warfare became a swift, mobile, and often spectacular affair. Raiding parties could cover vast distances in short periods, striking enemy camps and retreating before a counterattack could be mounted. Mounted charges, with warriors wielding lances, bows, and later firearms, became a defining feature of Plains warfare.

Horse theft, far from being a mere crime, became a highly esteemed act of bravery and a primary means of accumulating wealth and prestige. Counting coup – touching an enemy in battle – was considered the ultimate act of courage, and doing so on horseback, often while capturing an enemy’s horse, brought immense honor. Tribes like the Comanche became legendary "Lords of the Southern Plains," their military dominance fueled by their vast horse herds and unparalleled equestrian skills. The horse, in essence, became a strategic asset, a measure of a tribe’s power and a key factor in the ever-shifting alliances and rivalries across the Plains.

The horse’s impact extended profoundly to mobility and settlement patterns. Before the horse, tribes relied on dogs to pull travois – a type of sled made of two poles – for transporting possessions. This limited the size of dwellings and the amount of goods a family could carry. With horses, the travois could be scaled up significantly. A single horse could pull a load many times heavier than a dog, allowing for larger, more comfortable tipis. This meant families could carry more blankets, tools, food, and personal belongings, improving their quality of life.

The enhanced carrying capacity and speed of travel also facilitated a truly nomadic lifestyle, allowing tribes to follow the buffalo herds year-round and exploit seasonal resources across immense territories. This newfound mobility led to the expansion of tribal territories and increased interaction, both peaceful and hostile, between different groups. Trade networks expanded, and goods from distant regions could be exchanged more readily. The horse essentially freed Plains people from the constraints of limited transport, opening up vast new horizons.

Social structures underwent significant transformations. The ownership of horses became a primary indicator of wealth and status. An individual or family with numerous horses, often referred to as "horse rich," commanded respect and influence within the community. Conversely, being "horse poor" could signify a lower social standing. This new form of wealth led to a degree of social stratification not as pronounced in pre-equestrian societies.

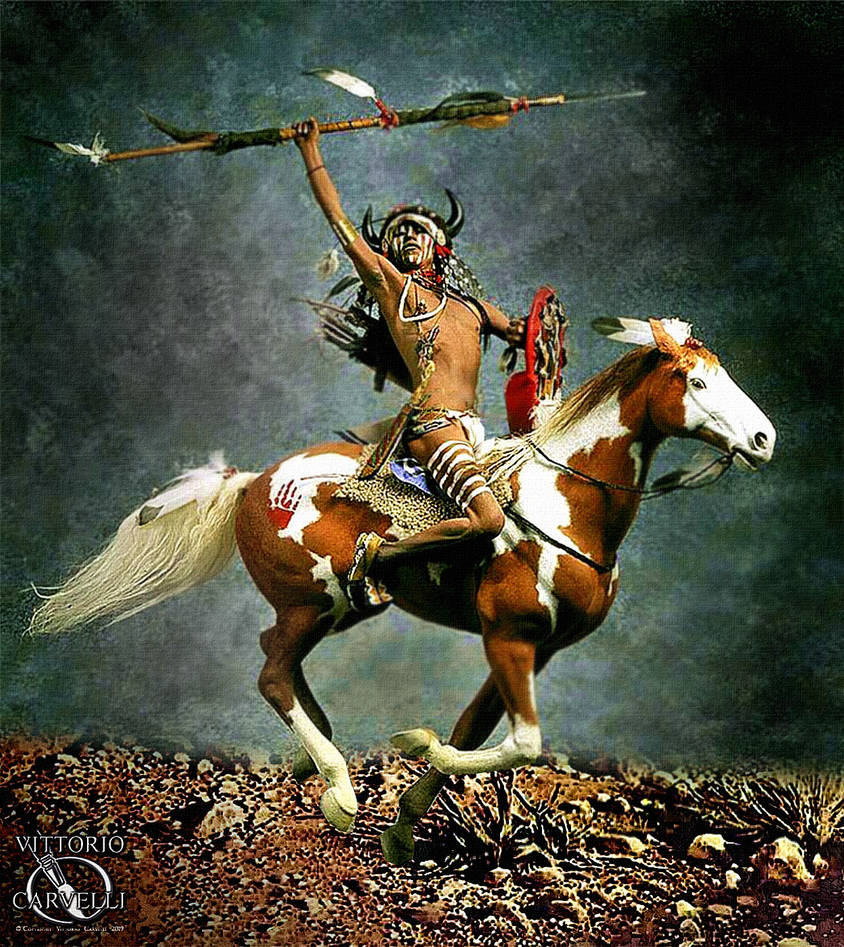

Warrior societies, which had always existed, gained immense prestige and power. Young men aspiring to leadership roles often proved their worth through equestrian prowess, successful horse raids, and bravery in mounted combat. A warrior’s personal honor was inextricably linked to his horses, and he would often adorn them with paint, feathers, and elaborate tack, reflecting his own achievements. Women’s roles also evolved; while men’s lives became more focused on hunting and warfare, women’s work in processing the increased supply of buffalo meat and hides became more productive and central to the tribe’s economic well-being.

Culturally and spiritually, the horse became deeply interwoven into the fabric of Plains life. It wasn’t just a tool or a possession; it was a companion, a partner, and often revered as a sacred being. Horses were incorporated into creation stories, ceremonies, songs, and dances. Warriors sought spiritual guidance from horse spirits, and medicine bundles often contained horsehair or other equine elements. The Lakota, for example, believed in the "Horse Dance" (Sunka Wakan Kaga), a powerful ceremony invoking the spirit of the horse for healing and success.

Artistic expressions, from ledger drawings to painted hides and tipi coverings, frequently depicted horses in scenes of hunting, battle, and daily life. The bond between a warrior and his war pony was profound, often seen as a spiritual connection. A Lakota saying encapsulates this sentiment: "A man without a horse is like a bird without wings." This spiritual reverence underscores how completely the horse had become integrated into the Indigenous worldview.

The peak of Plains horse culture, roughly from the mid-18th to the late 19th century, was a period of unprecedented dynamism and flourishing for many Native American nations. However, this golden age was tragically curtailed by the relentless westward expansion of the United States. The deliberate extermination of the buffalo herds, the reservation system, and the imposition of a sedentary lifestyle systematically dismantled the very foundations of horse-based nomadic culture. Tribes were stripped of their lands, their freedom to roam, and their primary economic resource, rendering their equestrian way of life unsustainable.

Despite this devastating decline, the legacy of the horse remains a powerful symbol of Native American resilience, ingenuity, and cultural richness. The image of the mounted warrior, a testament to skill, bravery, and a profound connection to the land and its creatures, endures as an iconic representation of Indigenous identity. The horse, arriving as a foreign animal, was transformed by Native Americans into the very heart of their existence, forever changing the course of their history and leaving an indelible mark on their traditions and spirit. The galloping revolution was a testament to human adaptability, a vibrant chapter in North American history where the spirit of a people rode in unison with the thunder of hooves across the vast, open Plains.