A Silent Crisis: The Enduring Challenges Plaguing Native American Health Services

WASHINGTON D.C. – In the vast, often remote landscapes of the United States, a quiet health crisis persists, largely unseen by the wider public. For generations, Native American communities have grappled with a healthcare system profoundly shaped by historical neglect, chronic underfunding, and systemic inequities. Despite a solemn federal trust responsibility enshrined in treaties and laws, the healthcare services provided to America’s Indigenous peoples remain critically under-resourced, leaving communities disproportionately affected by chronic diseases, mental health crises, and a persistent lack of access to quality care.

At the heart of this complex issue lies the Indian Health Service (IHS), an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, tasked with providing comprehensive health services to approximately 2.6 million American Indians and Alaska Natives across 37 states. Its mandate stems from a centuries-old commitment, where tribes ceded vast territories in exchange for the federal government’s promise to provide essential services, including healthcare. Yet, this promise, as many advocates argue, has been consistently broken.

"The federal government’s trust responsibility to provide healthcare is not charity; it’s a treaty obligation, a payment for the lands that now make up this nation," states Mary Jane Jones, a policy analyst for the National Congress of American Indians. "But what we see on the ground is a system starved of resources, struggling to meet even basic needs, let alone the complex health challenges facing our people."

A Foundation of Underfunding: The Root of All Ills

The most glaring challenge facing Native American health services is chronic, severe underfunding. While the national average for healthcare spending per person in the U.S. is well over $12,000 annually, the IHS per capita spending typically hovers around $4,000 to $5,000. This stark disparity creates a ripple effect that undermines every aspect of care delivery.

"Imagine trying to run a modern hospital with a budget from 30 years ago," says Dr. David Yazzie, a family physician working at an IHS clinic on the Navajo Nation. "Our facilities are often dilapidated, our equipment outdated, and we simply don’t have enough staff. We’re constantly making impossible choices – do we fix the broken MRI machine, or hire another nurse? Do we offer a full range of preventative care, or just focus on emergencies?"

This lack of funding translates directly into tangible deficiencies:

- Dilapidated Infrastructure: Many IHS facilities are old, poorly maintained, and lack the modern equipment necessary for comprehensive diagnostics and treatment. Some clinics operate out of trailers or buildings long past their prime.

- Workforce Shortages: Low salaries, isolated locations, and high caseloads make it incredibly difficult to recruit and retain doctors, nurses, and specialists. This leads to high turnover, burnout, and a reliance on temporary staff who may not understand the unique cultural context of the communities they serve.

- Limited Services: Essential services like specialized mental health care, dental care, and substance abuse treatment are often scarce or unavailable, forcing patients to travel hundreds of miles for care, if they can access it at all.

Geographic Isolation and Access Barriers

For many Native American communities, particularly those on remote reservations, geographic isolation compounds the problems of underfunding. Long distances to the nearest clinic or hospital, coupled with a lack of reliable transportation, present formidable barriers to care. A routine check-up can become an all-day ordeal, requiring hours of driving and significant personal expense.

"We have patients who live three hours away from our clinic, and that’s just one way," explains Sarah Many Horses, a community health representative in rural South Dakota. "If they don’t have a car, or can’t afford gas, or if the roads are impassable due to weather, they simply don’t come. They wait until it’s an emergency, and by then, it’s often much harder to treat."

The digital divide also plays a significant role. While telehealth has emerged as a crucial tool for expanding access to care, many tribal lands lack the broadband infrastructure necessary for reliable internet connectivity, leaving these communities behind in the digital healthcare revolution.

Disproportionate Health Burdens: The Weight of History

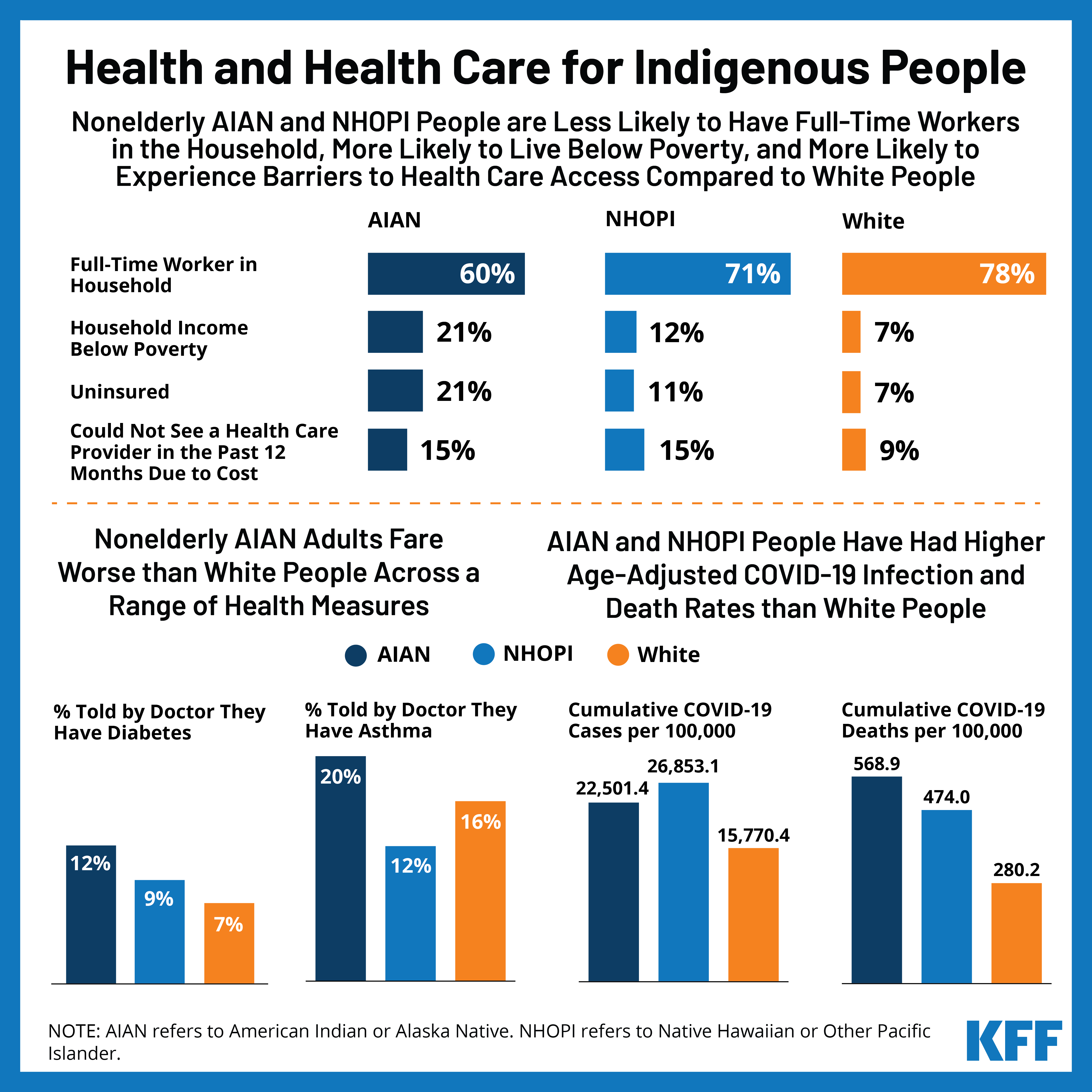

The challenges within the healthcare system are amplified by the profound health disparities that Native Americans face. They suffer from some of the highest rates of chronic diseases in the nation. For example, Native Americans are 2.2 times more likely to have type 2 diabetes than non-Hispanic whites. Heart disease, cancer, and stroke also disproportionately affect Indigenous populations. These disparities are not merely biological; they are deeply rooted in historical trauma, poverty, and environmental factors.

"Our health issues are not just about genetics or lifestyle choices; they are a direct consequence of colonization, forced relocation, the destruction of traditional food systems, and systemic discrimination," states Dr. Yazzie. "When people live with chronic stress, lack access to nutritious food, and face daily discrimination, their bodies respond. It’s a cumulative burden."

The Mental Health and Substance Abuse Crisis

Perhaps one of the most heartbreaking consequences of historical trauma and systemic neglect is the devastating mental health and substance abuse crisis gripping Native American communities. Generations of trauma—from the horrors of boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian, save the man," to the ongoing experience of racism and cultural erosion—have left deep wounds.

Native American youth have the highest suicide rates of any ethnic group in the U.S., a rate that is 1.5 times higher than the national average. Substance abuse, particularly alcoholism and the opioid crisis, also disproportionately affects these communities, often serving as a maladaptive coping mechanism for profound pain.

"We see the intergenerational trauma every day," says Elena Red Feather, a tribal elder and traditional healer. "Our young people carry the pain of their grandparents, who were punished for speaking their language. They face a world that often doesn’t understand them, and our clinics are overwhelmed, unable to provide the culturally sensitive counseling and support that is so desperately needed."

The integration of traditional healing practices with Western medicine is a growing area of focus, recognizing that holistic well-being often requires addressing spiritual and emotional health alongside physical ailments. However, funding for these integrated approaches remains scarce.

Jurisdictional Maze and Tribal Sovereignty

Navigating the complex web of federal, state, and tribal healthcare systems adds another layer of difficulty. Who pays for what? Where can a patient go if the IHS clinic can’t provide the necessary care? These questions often lead to delays, denials, and confusion, pushing patients further into medical debt or simply foregoing care.

However, amidst these challenges, there is a powerful movement towards tribal self-determination. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (P.L. 93-638) allows tribes to assume control and management of federal programs, including healthcare, previously administered by the IHS. This has led to the establishment of tribally run health programs, which often prove more effective because they are directly accountable to the communities they serve and can tailor services to local needs and cultural values.

"When tribes take over their healthcare, we see innovation, culturally appropriate care, and a renewed sense of ownership," says Mary Jane Jones. "They are building their own systems, integrating traditional healing, focusing on prevention, and hiring their own people. But even with self-governance, the core issue of underfunding persists. Tribes are left to do more with the same, insufficient federal dollars."

A Path Forward: Investment and Respect

Addressing the healthcare crisis in Native American communities requires a multi-faceted approach, beginning with a significant and sustained increase in federal funding to meet the government’s trust responsibility. This means bringing IHS per capita spending up to par with other federal healthcare programs like Medicare or Medicaid.

Beyond funding, solutions include:

- Infrastructure Investment: Modernizing and expanding clinics, hospitals, and residential treatment centers.

- Workforce Development: Creating incentives for healthcare professionals to work in tribal communities, including loan repayment programs and pathways for Indigenous students to enter healthcare fields.

- Broadband Expansion: Ensuring reliable internet access for telehealth services.

- Cultural Competency: Training all healthcare providers on Indigenous cultures, histories, and health beliefs.

- Support for Tribal Self-Governance: Empowering tribes to continue designing and delivering their own healthcare solutions.

The challenges facing Native American health services are profound, deeply entrenched, and reflective of a long history of neglect. Yet, the resilience, strength, and unwavering commitment of Native American communities to heal and thrive offer a powerful counter-narrative. The path forward demands not just more resources, but a fundamental shift in how the nation views its obligations – a recognition that fulfilling the promise of healthcare for its First Peoples is not merely a matter of policy, but of justice, equity, and human dignity. The time for this silent crisis to be addressed is long overdue.