The Unseen Riches: Native American Generosity and the Communal Fabric of Wealth

In the popular imagination, the concept of wealth often conjures images of gold, sprawling estates, or overflowing bank accounts. It is a metric typically associated with accumulation, individual success, and often, scarcity for others. Yet, for thousands of years, across the diverse tapestry of North America, indigenous peoples practiced a profoundly different, often counter-intuitive, form of wealth and distribution. Their systems, built on principles of generosity, reciprocity, and communal well-being, offer a powerful counter-narrative to capitalist individualism and provide enduring lessons for a world grappling with inequality and environmental degradation.

This article delves into the intricate customs of Native American generosity and wealth distribution, exploring how these practices forged resilient communities, defined leadership, and fostered a deep connection to the land and all living beings. It seeks to illuminate a sophisticated societal structure where giving, not hoarding, was the ultimate measure of true affluence.

Redefining Wealth: Beyond Material Accumulation

To understand Native American wealth distribution, one must first deconstruct the Western definition of "wealth." For most indigenous cultures, wealth was not merely about material possessions, though these certainly existed. True wealth encompassed a broader spectrum: the health and well-being of the entire community, the abundance of natural resources, spiritual knowledge, strong social ties, the respect of one’s peers, and a harmonious relationship with the natural world.

The land itself was not a commodity to be owned but a living entity, a sacred trust from the Creator, providing sustenance and spiritual grounding. As such, the concept of "owning" land in the European sense was largely alien. Instead, tribes held territories communally, and resources were managed with an eye towards long-term sustainability and the needs of future generations. This inherent connection to the land informed every aspect of their economic and social systems.

The Philosophy of Reciprocity: A Sacred Trust

At the heart of Native American generosity lay the principle of reciprocity – a profound understanding that all life is interconnected and that giving creates a web of mutual obligation and support. It wasn’t charity in the modern sense, which often implies a power imbalance, but a cyclical exchange that strengthened social bonds. When one gave, it was understood that, when the need arose, others would give in return. This created a robust safety net, ensuring that no member of the community was left to suffer in isolation.

The Lakota concept of Mitakuye Oyasin – "all my relations" – encapsulates this philosophy. It extends beyond human kinship to include all living beings, the earth, and the cosmos. This worldview fostered a deep sense of responsibility for the welfare of the whole, rather than just the individual. Resources, whether a successful hunt, a bountiful harvest, or skilled craftsmanship, were seen as blessings to be shared, not hoarded.

Potlatch: A Grand Expression of Generosity and Status

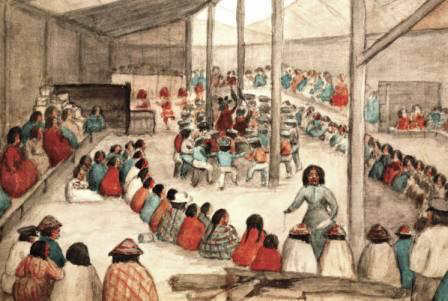

Perhaps the most famous and elaborate example of Native American wealth distribution is the Potlatch of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, including the Kwakwaka’wakw, Haida, Tlingit, and Nuu-chah-nulth. Far from being a mere feast, the Potlatch was a complex ceremonial gathering that served multiple vital functions:

- Redistribution of Wealth: The central act of a Potlatch was the giving away of vast quantities of goods – blankets, canoes, carved masks, food, and even copper shields – by the host family or clan.

- Validation of Status and Events: A Potlatch was held to mark significant life events: a birth, a marriage, a death, the raising of a totem pole, or the transfer of inherited titles and privileges. The more lavish the gifts given, the greater the prestige and social standing earned by the host. It was a demonstration of the host’s ability to provide for their community and their commitment to its welfare.

- Social Cohesion and Diplomacy: These ceremonies brought together different clans and sometimes even rival tribes, fostering alliances, resolving disputes, and reinforcing social structures.

- Economic Regulation: Potlatches stimulated production and trade, as goods were created specifically for these events. They also ensured that wealth did not stagnate in the hands of a few but continually circulated through the community.

The sheer scale of generosity at a Potlatch often astonished European observers, who mistakenly viewed it as wasteful and irrational. Yet, for the indigenous peoples, it was a highly rational and effective system for maintaining social order, economic balance, and cultural continuity. As anthropologist Franz Boas noted in his studies of the Kwakwaka’wakw, "The object of the potlatch is to maintain the status of the chief, or to raise it, by the distribution of property." To give away was to gain power; to hoard was to lose it.

Giveaways: The Heart of Plains Generosity

While the Potlatch was unique to the Northwest, the practice of "giveaways" was common across many other Native American nations, particularly among the Plains tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Crow. Giveaways were often associated with significant life events, much like the Potlatch, but were generally less formal and focused on direct support for those in need.

A successful hunter might share his entire kill with the village. A family mourning a loved one might distribute all their possessions to ease their grief and honor the deceased, knowing the community would support them in return. Warriors returning from a successful raid or a chief celebrating a major achievement would host a giveaway, distributing horses, blankets, and other valuable items. In these societies, a leader’s authority was not derived from how much they owned, but from how much they gave away. The "richest" man was often the one with the fewest personal possessions, having shared everything with his people.

"We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding rivers as ‘wild,’" said Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca Nation. "Only to the white man was nature a ‘wilderness’ and only to him was the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and ‘savage’ people. To us, it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery." This perspective naturally led to a system of gratitude and sharing rather than exploitation and hoarding.

The Clash of Worldviews: Colonial Suppression

The profound differences between Native American and European concepts of wealth and ownership led to immense misunderstandings and, ultimately, to systematic suppression. European colonizers, driven by capitalist ideologies of individual accumulation and private property, viewed indigenous communal practices as "primitive," "inefficient," and even "barbaric." The Potlatch, in particular, was seen as an impediment to "civilization" and Christianization.

Both the Canadian and US governments, in their assimilation policies, outlawed the Potlatch and other giveaway ceremonies for decades. In Canada, the ban on the Potlatch lasted from 1884 to 1951, leading to arrests, confiscations of sacred regalia, and immense cultural trauma. Yet, these practices often went underground, sustained by the unwavering commitment of community members, demonstrating their fundamental importance to indigenous identity and survival.

Enduring Legacy and Modern Relevance

Despite centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, and economic hardship, the spirit of generosity and communal distribution endures in Native American communities today. Modern powwows often include giveaways, honoring individuals and strengthening community bonds. Tribal nations are increasingly asserting their sovereignty and revitalizing traditional economic practices, sometimes integrating them with contemporary models.

The lessons embedded in these ancient customs are remarkably relevant for the challenges facing the modern world:

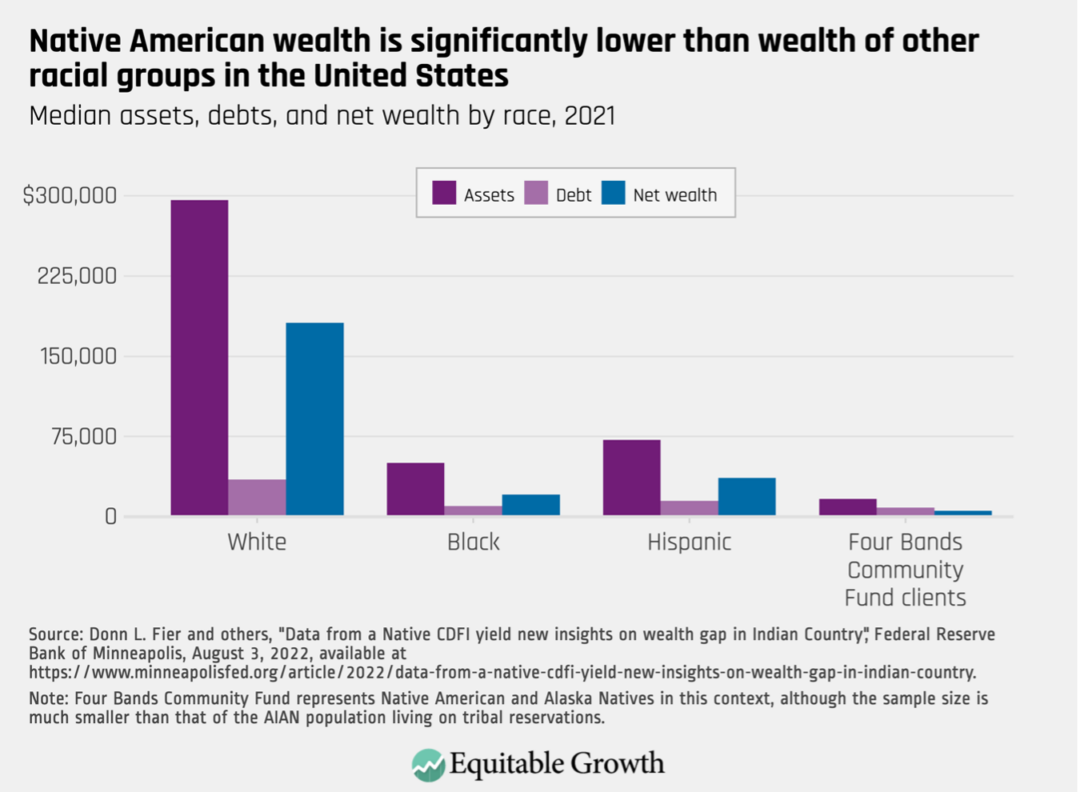

- Addressing Inequality: Native American systems offered inherent mechanisms to prevent extreme wealth disparity, ensuring a baseline of well-being for all.

- Sustainability: The deep reverence for the land and the practice of managing resources for future generations stand in stark contrast to unsustainable consumption patterns.

- Community Resilience: The focus on mutual aid and strong social networks built incredibly resilient communities capable of weathering hardship.

- Redefining Success: These customs challenge us to consider whether true success lies in individual accumulation or in the collective flourishing of society.

As the world grapples with climate change, economic disparities, and social fragmentation, the wisdom embedded in Native American generosity and wealth distribution customs offers a powerful alternative. It reminds us that true wealth may not be found in what we can acquire, but in what we are willing to share, and that the strength of a society is measured not by its richest members, but by the well-being of its most vulnerable. The unseen riches of indigenous generosity continue to offer a beacon for a more equitable and sustainable future.