Silent Glides and Enduring Craft: The Timeless Art of Native American Canoe Building

More than mere vessels, Native American canoes are profound testaments to ingenuity, deep ecological knowledge, and an unbreakable connection to land and water. For millennia, across the vast and varied landscapes of North America, these traditional watercraft served as lifelines – enabling trade, facilitating travel, sustaining communities through hunting and fishing, and playing central roles in ceremony and warfare. The art of their construction, a meticulous blend of science, skill, and spirituality, represents one of humanity’s most remarkable achievements in natural resource utilization and engineering.

The sheer diversity of Native American canoes reflects the equally diverse environments and cultures that birthed them. While the iconic birchbark canoe often comes to mind, the continent saw a spectrum of designs, from massive dugout canoes carved from single logs to elegant skin-on-frame kayaks and umiaks in the Arctic. Each design was perfectly adapted to its specific waterways and purposes, showcasing a profound understanding of hydrodynamics, material properties, and local ecology.

The Birchbark Masterpiece: A Symphony of Nature’s Gifts

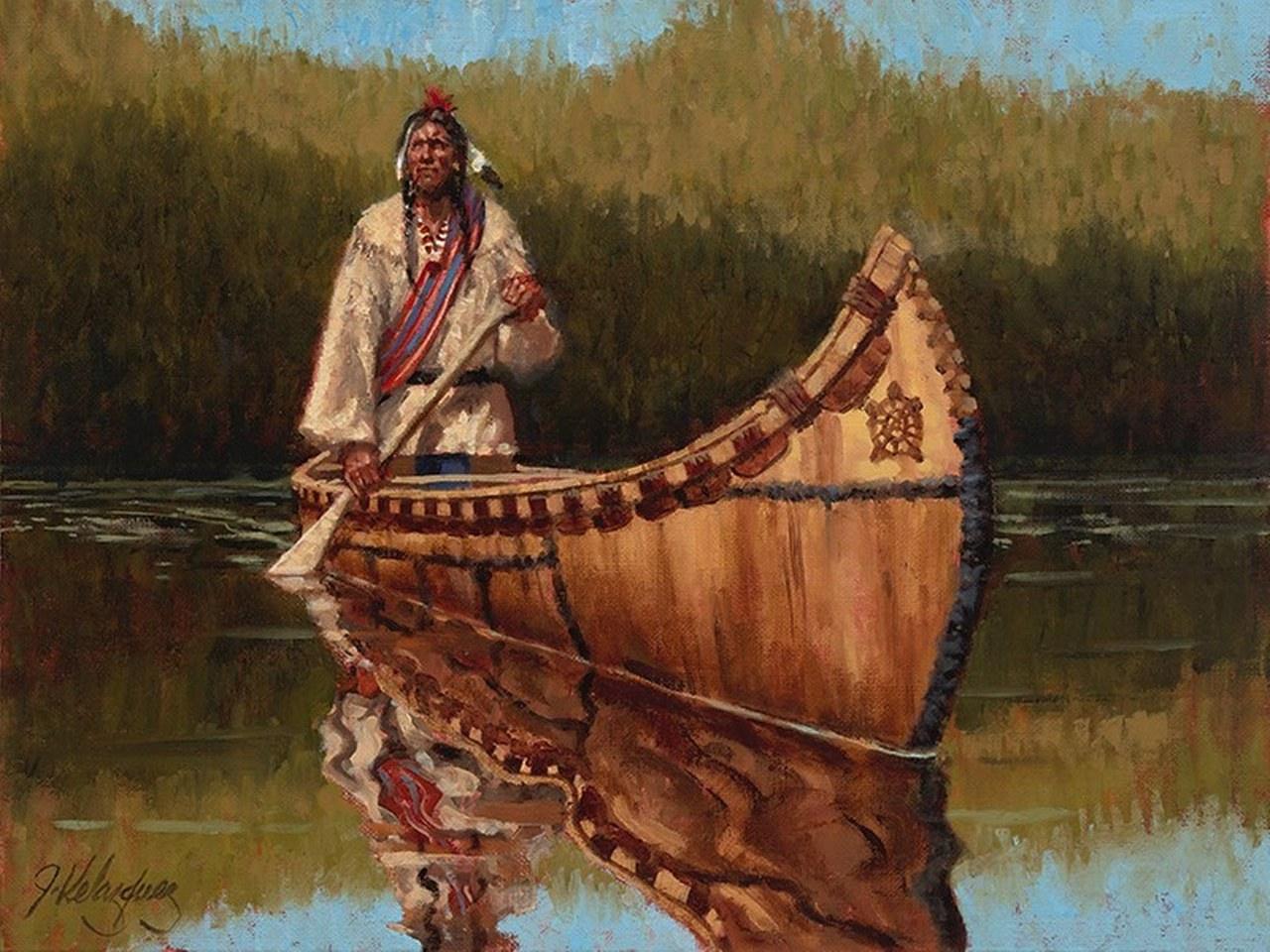

Perhaps the most celebrated of these watercraft is the birchbark canoe, particularly iconic among the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Cree, and Wabanaki peoples of the Great Lakes and Northeastern Woodlands. These canoes are marvels of lightweight strength and flexibility, capable of navigating both swift rivers and expansive lakes. The process of building one is a multi-season endeavor, beginning with the respectful harvest of materials.

The primary material, birchbark (specifically from the paper birch, Betula papyrifera), is collected in late spring or early summer when the sap is running, allowing the bark to be peeled in large, pliable sheets. The quality of the bark is paramount; builders seek trees with thick, smooth bark, free of knots and blemishes. "The birch tree gives its skin, and we have to treat it with respect," says master builder Ferdy Goode, a member of the Nipissing First Nation, emphasizing the spiritual reciprocity inherent in the craft. "It’s not just taking; it’s asking permission."

Once harvested, the bark sheets are carefully laid out, often on a prepared bed of earth or sand, bark-side down. A wooden frame, often made of cedar or spruce, is then placed on top, defining the shape of the canoe. The bark is meticulously folded and cut, then held in place by stakes driven into the ground. Inside, a skeleton of thin, flexible cedar ribs and sheathing (thin strips of wood) is installed, providing structural integrity and shaping the hull. The ribs are steam-bent to achieve their characteristic curvature, a process requiring precise timing and feel.

The various components—the bark, cedar gunwales (the top edges of the canoe), thwarts (cross-braces), and ribs—are lashed together using spruce root, which is incredibly strong and flexible when split and soaked. Holes for lashing are made with bone or metal awls. The final, crucial step is waterproofing. All seams and holes are sealed with a mixture of spruce gum or pine pitch, often mixed with animal fat and charcoal for added durability and flexibility. This pitch, heated and applied while warm, creates an impenetrable barrier against water. The entire process is a testament to the builders’ deep knowledge of forest resources and their ability to transform them into an elegant, functional vessel using only hand tools.

Dugout Giants: Carving the Forest into Watercraft

Further west, particularly among the sophisticated maritime cultures of the Pacific Northwest, dugout canoes reigned supreme. These monumental canoes, carved from single logs, predominantly cedar (Western Red Cedar, Thuja plicata, prized for its straight grain, lightness, and rot resistance), were engineering marvels in their own right. Peoples like the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish crafted canoes ranging from nimble fishing vessels to massive whaling and war canoes exceeding 60 feet in length, capable of carrying dozens of warriors or thousands of pounds of trade goods.

The construction of a dugout canoe began with the careful selection of an old-growth cedar tree, a sacred act often accompanied by ceremony. Once felled, the arduous process of carving began. Historically, tools included stone adzes, chisels, and controlled fire. Fire was often used to hollow out the log, with the charred wood then scraped away with adzes. This iterative process of burning and scraping continued until the desired thickness was achieved.

Achieving the correct hull shape and thickness was critical for stability and speed. Builders would often fill the partially carved canoe with water and hot stones to steam and soften the wood, then spread the gunwales apart with cross-braces to widen the beam, creating the graceful, flared sides characteristic of Pacific Northwest canoes. This "spreading" technique not only improved stability but also enhanced the canoe’s carrying capacity. The bow and stern were often intricately carved with animal forms or ancestral crests, reflecting the spiritual and clan affiliations of the owners.

"For the Haida, the cedar tree is a living relative," observes anthropologist Dr. Sarah Morton. "Transforming it into a canoe is an act of deep reverence, a conversation between carver and wood. Every stroke of the adze, every shaping of the hull, embodies generations of inherited wisdom and respect."

In the southeastern United States, tribes like the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Seminole also built dugout canoes, often from cypress or yellow poplar, for navigating rivers and swamps. Their designs were typically simpler than their Pacific Northwest counterparts, reflecting different environmental demands and cultural aesthetics, but equally effective for their purposes.

Beyond Utility: Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions

Regardless of material or design, the construction of a Native American canoe was never merely a technical exercise. It was imbued with profound cultural and spiritual significance. The entire process was often a community endeavor, reinforcing social bonds and transmitting knowledge from elders to youth. Harvesting materials involved prayers and offerings, acknowledging the spirit of the tree or the animal whose skin would be used. The finished canoe was seen as a living entity, an extension of the people who built and used it, carrying their stories, their history, and their connection to the natural world.

Canoes facilitated not just physical travel but also cultural exchange. They were vital for trade networks that spanned continents, allowing the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies. They were also central to ceremonies, gatherings, and, unfortunately, conflicts. Their presence on the water was a powerful symbol of tribal sovereignty and self-reliance.

A Resurgence of Tradition: Keeping the Craft Alive

The arrival of European colonizers brought profound disruptions to these traditions. Diseases, warfare, forced assimilation, and the introduction of new technologies like motorized boats led to a decline in traditional canoe building. Many skills were nearly lost, and the spiritual connections to the materials were fractured.

However, today, a powerful resurgence of traditional canoe building is underway across North America. Indigenous communities are actively reclaiming and revitalizing these ancient practices, recognizing them as vital to cultural preservation, identity, and sovereignty. Master builders, often elders who learned from their grandparents, are diligently teaching younger generations. Cultural centers and tribal programs host workshops, inviting community members to participate in every stage of construction, from harvesting bark to lashing ribs.

Individuals like Wayne Valliere (Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe) and the teams at the Coquille Indian Tribe’s Canoe Journey programs on the Pacific Northwest coast are spearheading these efforts. They are not just building canoes; they are rebuilding cultural pride, fostering intergenerational learning, and connecting youth to their heritage and the land.

"Every time we build a canoe, we’re not just building a vessel; we’re rebuilding our nation," says Travis Courville, a cultural preservationist from the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. "It’s about our language, our songs, our connection to the water, and our future."

Challenges persist, particularly in sourcing suitable materials. Old-growth cedar is scarce, and finding large, unblemished birchbark sheets requires careful management of forest resources. Yet, these challenges only underscore the dedication and resilience of those committed to the craft. The revival of canoe building also sparks conversations about environmental stewardship, as communities work to ensure the health of the forests and waterways that provide these invaluable resources.

The journey of Native American canoe building is far from over. With each new canoe launched, whether a sleek birchbark vessel gliding across a quiet lake or a majestic dugout cutting through ocean swells, an ancient spirit is reawakened. These watercraft stand as enduring symbols of Indigenous innovation, resilience, and an unbroken bond between people, their heritage, and the natural world – silent glides carrying forth timeless wisdom.