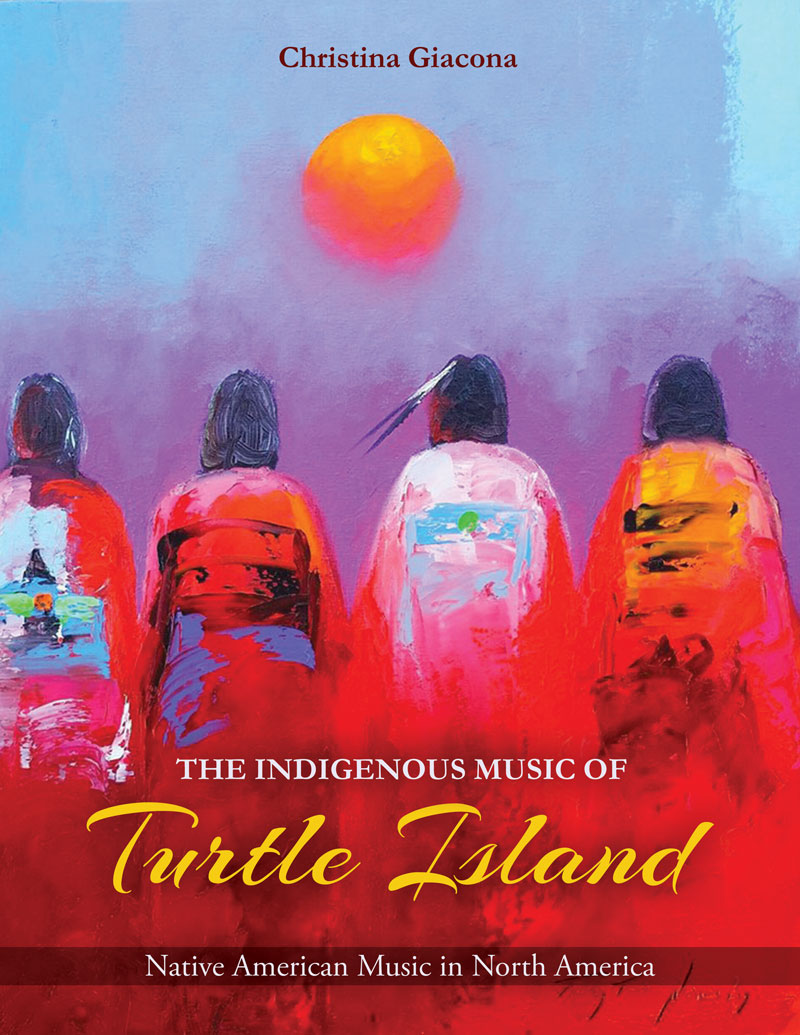

Echoes of Eternity: The Enduring Musicology of Turtle Island Indigenous Traditions

The soundscape of Turtle Island, known today as North America, resonates with an ancient, complex, and deeply spiritual musical heritage that stands as a testament to the enduring resilience and vibrant cultures of its Indigenous peoples. Far from a monolithic entity, Indigenous music across these lands is a vast tapestry woven from hundreds of distinct nations, languages, and worldviews, each contributing unique rhythms, melodies, and ceremonial practices. To delve into the musicology of Turtle Island is to embark on a journey into the heart of Indigenous identity, history, and spiritual connection.

At its core, Indigenous music on Turtle Island is rarely, if ever, mere entertainment. It is a profound, functional art form deeply integrated into the fabric of daily life and sacred ceremony. Songs serve as historical archives, legal texts, healing modalities, prayers, and conduits for communication with the spiritual realm. They mark rites of passage, celebrate harvests, mourn losses, tell creation stories, and transmit knowledge from one generation to the next. As countless Indigenous knowledge keepers affirm, "Music is life. It is our history, our law, our prayer." This sentiment underscores a fundamental truth: to understand the music is to understand the people.

The sheer diversity of these traditions is staggering. From the haunting, often high-pitched vocables and powerful drumbeats of the Plains Nations’ powwow songs to the intricate, story-telling cycles of the Northwest Coast, or the contemplative, flute-led melodies of the Eastern Woodlands, each nation possesses a distinct musical language. The Inuit throat singing (katajjaq) of the Arctic, for instance, is a mesmerizing vocal game often performed by two women, producing complex, guttural, and resonant sounds that mimic natural phenomena like wind, water, and animal calls. This contrasts sharply with the communal, unison singing of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people, where songs accompany social dances and agricultural ceremonies, often led by a water drum and horn rattles.

One of the most defining characteristics of Turtle Island Indigenous musicology is its reliance on oral tradition. Songs are passed down aurally, meticulously taught and memorized, ensuring their integrity over millennia. This oral transmission is not a casual process; it is a rigorous pedagogical system where elders, specialized singers, or ceremonial leaders impart songs, their meanings, and their appropriate contexts to younger generations. The loss of Indigenous languages, a direct consequence of colonization and forced assimilation policies like the residential school system, poses a significant threat to the survival of many of these musical traditions, as songs are intrinsically linked to their linguistic and cultural contexts. However, language revitalization efforts often incorporate songs as powerful tools for cultural reclamation.

Instrumentation across Turtle Island is diverse yet often shares common archetypes. The drum, in its myriad forms, is perhaps the most ubiquitous and spiritually significant instrument. From the large, communal powwow drum, often referred to as the "heartbeat of Mother Earth," to smaller hand drums, frame drums, and water drums (like those used by Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples, filled with a small amount of water to create a unique resonant sound), drums anchor most musical performances. Rattles, crafted from gourds, turtle shells, deer hooves, or other natural materials, provide rhythmic accompaniment and are often imbued with symbolic meaning, representing the voices of animals or spirits. Flutes, typically made from wood or bone, produce melodic, often melancholic sounds, particularly prominent in courting songs or contemplative pieces, notably among Plains and Southwest nations. The human voice, however, remains the primary and most versatile instrument, with a vast repertoire of vocalizations including vocables (non-lexical syllables), falsetto, tremolo, and various forms of calls and shouts.

The structure of Indigenous music often differs significantly from Western classical paradigms. Harmony in the Western sense is less common; instead, unison singing, heterophony (slight variations in melody among singers), and call-and-response patterns are prevalent. Repetition is a core structural element, not as a lack of complexity, but as a deliberate means of emphasis, trance induction, and communal participation. Songs often cycle through verses or phrases, building in intensity and allowing for collective immersion in the music’s spiritual or social purpose.

A crucial aspect of Indigenous musicology is the concept of ownership and sacredness. Many songs are not public domain; they are considered intellectual property belonging to specific individuals, families, clans, or ceremonial societies. Some are deeply sacred, revealed through dreams or visions, or gifted by spirit beings, and are only to be performed in specific contexts by designated individuals. The appropriation and commercial exploitation of these songs by non-Indigenous individuals or entities without permission is a serious breach of cultural protocol and has been a source of significant pain and injustice. This principle of ownership extends beyond mere copyright; it is a spiritual and cultural trust.

The devastating impact of colonialism on Indigenous musical traditions cannot be overstated. Policies designed to "kill the Indian in the child," such as residential schools, actively suppressed Indigenous languages, ceremonies, and music. Children were punished for speaking their languages or singing traditional songs, leading to generations of cultural rupture. Many songs were lost, and the vital intergenerational transmission was severely disrupted. This era left deep wounds, but it also ignited an extraordinary spirit of resilience and cultural revitalization.

Today, Indigenous music on Turtle Island is experiencing a powerful renaissance. Elders are diligently working to pass on traditional knowledge, often through community-led language and culture camps. Contemporary artists are exploring innovative fusions, blending traditional sounds with modern genres like hip-hop, electronic, rock, and folk. Groups like A Tribe Called Red, with their "Electric Powwow" sound, exemplify this fusion, taking traditional powwow beats and vocables and marrying them with electronic dance music, bringing Indigenous voices to a global audience. Artists like Buffy Sainte-Marie have long championed Indigenous rights through song, while a new generation, including The Halluci Nation (formerly A Tribe Called Red), Snotty Nose Rez Kids, and Jeremy Dutcher, continues to push boundaries, challenge stereotypes, and amplify Indigenous narratives.

The emergence of Indigenous musicologists and scholars is also transforming the field. For too long, the study of Indigenous music was dominated by non-Indigenous researchers, often applying Western analytical frameworks that failed to grasp the nuanced cultural contexts. Today, Indigenous scholars are reclaiming this intellectual space, conducting research from within their own cultural paradigms, emphasizing Indigenous epistemologies, and ensuring that the study of their music is respectful, relevant, and rooted in community values. This decolonization of musicology is vital for accurate representation and the preservation of these unique sonic heritages.

In conclusion, the musicology of Turtle Island Indigenous music is a vibrant, living field of study that encompasses millennia of human creativity, spirituality, and cultural resilience. It demands respect, deep listening, and an understanding that these sounds are not just notes and rhythms, but carriers of history, identity, and profound meaning. As these traditions continue to evolve, adapt, and reclaim their rightful place on the global stage, they offer a powerful reminder of the enduring strength of Indigenous peoples and the timeless echoes of their sacred and vital songs. To truly hear the music of Turtle Island is to hear the heartbeat of the land and its first peoples, forever resonating with stories, prayers, and an unyielding spirit.