The Unyielding Stand: Captain Jack and the Modoc War, a Battle for Home and Honor

In the desolate, unforgiving landscape of the Lava Beds of northern California, a small band of Modoc warriors, led by a man known to history as Captain Jack, made their final, desperate stand. For seven harrowing months in 1872-1873, they defied the might of the United States Army, transforming a volcanic wilderness into an impenetrable fortress. The Modoc War, often overshadowed by larger conflicts, stands as a poignant and tragic chapter in American history—a stark testament to the resilience of Indigenous peoples and the brutal cost of broken promises.

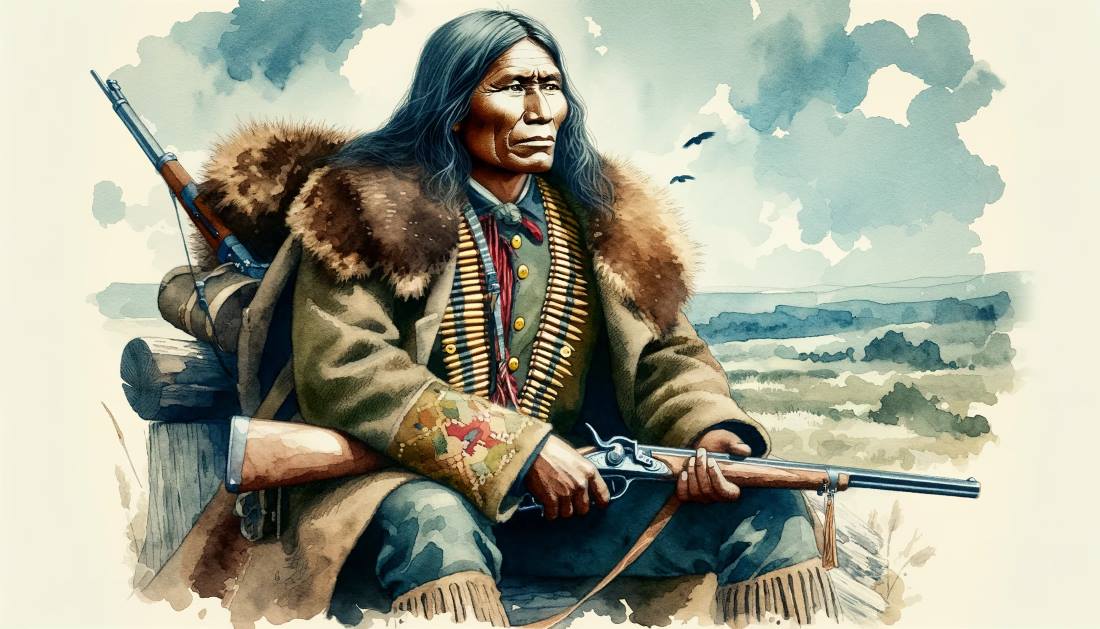

At its heart, this was a war for land, for identity, and for the right to simply exist on ancestral ground. Kintpuash, or Captain Jack as the settlers called him due to his preference for military-style coats, was not a traditional war chief. He was, by many accounts, a reluctant warrior, a pragmatist who initially sought peace and accommodation. Yet, circumstances, fueled by governmental ineptitude, settler encroachment, and the desperate pleas of his people, thrust him into a role that would etch his name into the annals of resistance.

The Modoc’s troubles began long before the first shot was fired. Their ancestral lands, stretching around Tule Lake and the Lost River in what is now southern Oregon and northern California, were rich in resources and deeply intertwined with their cultural identity. However, with the relentless westward expansion of American settlers, their way of life was increasingly threatened. The Treaty of 1864, signed by Modoc leaders under duress, forced them onto the Klamath Reservation, a territory already occupied by their traditional rivals, the Klamath people.

Life on the Klamath Reservation was intolerable. The Modocs faced starvation, harassment, and neglect from federal agents who often prioritized the Klamath. Captain Jack, witnessing the suffering of his people, led a faction of about 150 Modocs back to their traditional lands on the Lost River in 1870. They sought only to live in peace, cultivating their own fields. However, their return ignited tensions with white settlers who viewed their presence as an infringement on their claims.

The federal government, attempting to resolve the escalating conflict, issued conflicting orders. Sometimes they tried to negotiate a separate reservation for Captain Jack’s band; other times, they demanded their immediate return to Klamath. This vacillation, coupled with the settlers’ insistent demands, created an explosive situation. The powder keg finally ignited on November 29, 1872.

A company of US cavalry, under Captain James Jackson, was dispatched to force Captain Jack’s band back to the Klamath Reservation. A tense standoff at the Modoc camp on the Lost River quickly escalated into violence. Accounts differ on who fired first, but the exchange of gunfire resulted in casualties on both sides, including the deaths of several Modoc warriors and women, and the wounding of an American soldier. Simultaneously, a separate group of Modoc warriors, led by Hooker Jim, retaliated by attacking settlers along the Lost River, killing 13. These acts, though perpetrated by a different faction and not directly ordered by Captain Jack, irrevocably set the stage for war.

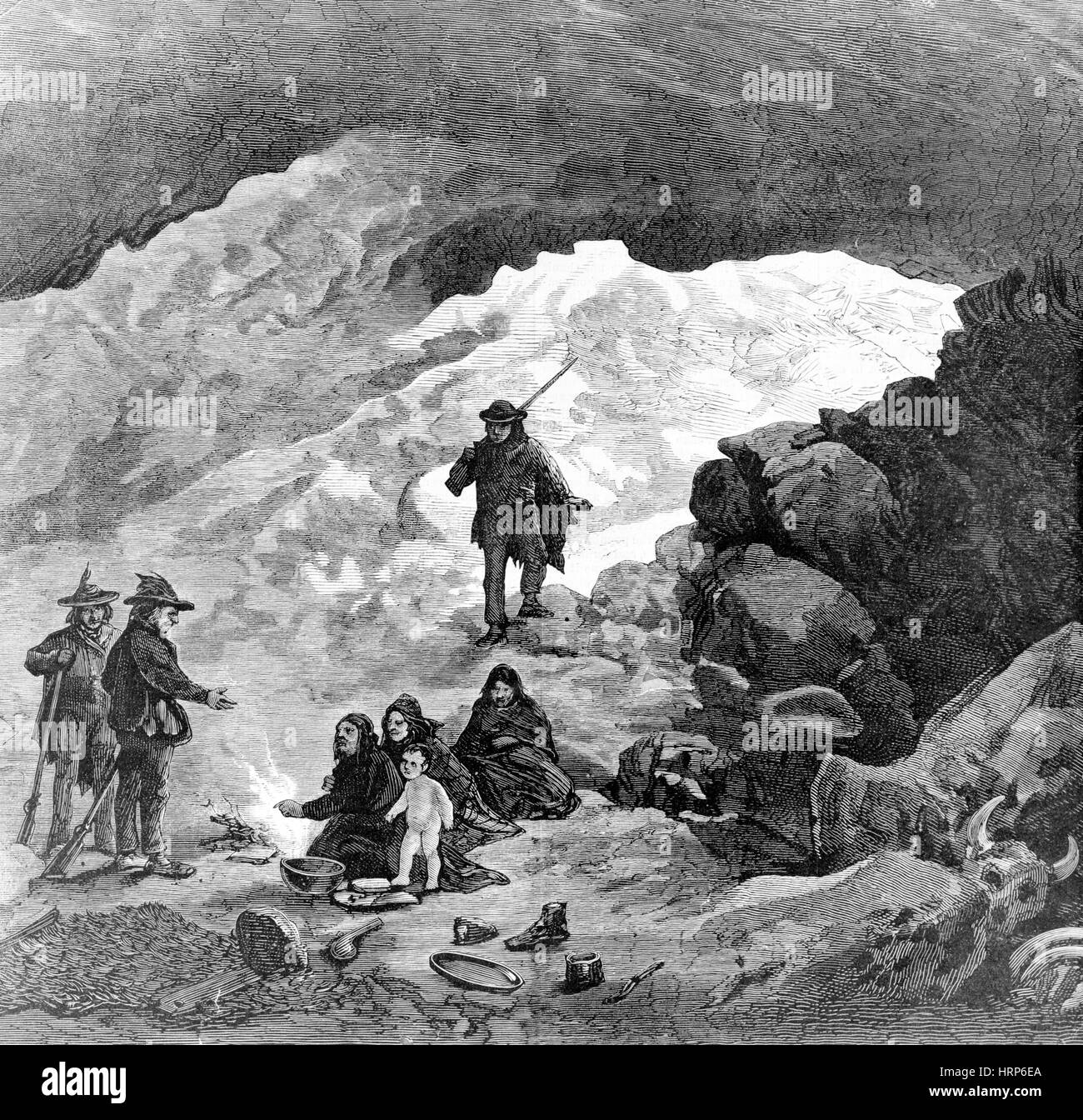

Knowing that their small numbers stood no chance against the full might of the US Army in open combat, Captain Jack made a strategic decision that would define the war: he led his people into the Lava Beds, a nightmarish labyrinth of volcanic rock, caves, and chasms south of Tule Lake. This desolate region, known to the Modocs as "The Land of Burnt-Out Fires," became their sanctuary and their greatest weapon.

The Lava Beds were an ideal defensive position. The rugged terrain, with its countless natural trenches and fortified caves, provided perfect cover and concealment. The Modocs, intimately familiar with every twist and turn, every hidden spring, could move with stealth and precision, while the heavily armed, uniformed US soldiers struggled to navigate the treacherous ground.

The first major military assault on the Lava Beds came on January 17, 1873. A force of over 400 soldiers, confident in their numerical superiority, advanced into the stronghold. What followed was a humiliating defeat for the US Army. The Modoc warriors, numbering only about 50, utilized their knowledge of the terrain and their marksmanship to devastating effect. They inflicted heavy casualties on the bewildered soldiers, who found themselves exposed and disoriented in the maze-like environment. The Army suffered 35 killed and many more wounded, while the Modocs sustained no casualties. The battle was a stark illustration of the power of defensive terrain and Indigenous tactical genius.

The shocking defeat sent ripples through Washington D.C. It became clear that a military solution would be costly and prolonged. A Peace Commission was formed, headed by General Edward R.S. Canby, a respected Civil War veteran, along with Reverend Eleazer Thomas and Alfred B. Meacham, the former Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon. Their mission was to negotiate a peaceful end to the conflict.

Multiple parleys were held, often in a tent set up between the Modoc lines and the Army encampment. Captain Jack, still hoping for a peaceful resolution, consistently demanded a small, separate reservation on the Lost River, where his people could live undisturbed. The commissioners, however, were bound by their instructions: the Modocs must surrender and return to the Klamath Reservation, or be exiled to Indian Territory. The chasm between their demands was too wide.

Adding to the tension were the “hotheads” within Captain Jack’s own band, particularly the faction led by Hooker Jim, who advocated for war. They pressured Captain Jack, accusing him of weakness and threatening to kill him if he did not agree to a more aggressive stance. Captain Jack, caught between the unyielding demands of the US government and the increasingly desperate and vengeful cries of his own warriors, found himself in an impossible position. He knew that killing the peace commissioners would seal his people’s fate, but he also feared for his own life if he resisted his warriors’ will.

On April 11, 1873, during another peace parley, the unthinkable happened. Under immense pressure from his war council, Captain Jack, with a heavy heart, agreed to the Modoc plan: to kill the commissioners as a desperate act of defiance and a final attempt to secure their land. As the peace talks faltered, Captain Jack, on a pre-arranged signal, drew a pistol and shot General Canby, killing him instantly. Reverend Thomas was also killed, while Meacham and another commissioner were severely wounded but managed to escape.

The assassination of General Canby, a high-ranking US Army officer and a peace emissary, sent shockwaves across the nation. It was an unprecedented act that hardened public opinion against the Modocs and galvanized the US government to pursue a military solution with renewed ferocity. The Modoc War was no longer just a local skirmish; it was an affront to national honor.

The military response was swift and overwhelming. General Jefferson C. Davis, a veteran of the Civil War, took command, bringing with him a force of over 1,000 soldiers, including artillery and even Indian scouts from other tribes. The Army systematically besieged the Lava Beds, cutting off water supplies and gradually pushing the Modocs further into their stronghold. Despite their valiant resistance, the Modocs were slowly starved and dehydrated. The terrain that had once been their ally now became their prison.

Internal divisions within Captain Jack’s band also began to surface. Some, like Hooker Jim, fearing retribution for the murders they had committed, advocated continued fighting. Others, exhausted and facing starvation, began to surrender. In May 1873, a Modoc faction, including Hooker Jim, surrendered to the Army, agreeing to help track down Captain Jack in exchange for amnesty for their crimes. This betrayal further weakened Captain Jack’s position.

By early June, Captain Jack’s remaining band, numbering only a few dozen, was on the run, desperate for food and water. On June 1, 1873, he was finally cornered and captured by a detachment of cavalry. His surrender marked the end of the Modoc War.

The aftermath was swift and brutal. Captain Jack, along with three other Modoc warriors—Boston Charley, Black Jim, and Schonchin John—were charged with murder for the deaths of General Canby and Reverend Thomas. Their trial, held by a military commission at Fort Klamath, was a deeply flawed affair. Despite arguments that Captain Jack acted under duress from his own warriors and that the commissioners were killed during wartime, the verdict was predetermined. All four were found guilty and sentenced to hang.

On October 3, 1873, Captain Jack and his three compatriots were executed at Fort Klamath. Their bodies were later exhumed and their heads sent to the Army Medical Museum in Washington D.C. for "scientific study," a grim and dehumanizing act that further underscores the injustices of the era.

The remaining Modocs, numbering fewer than 100, were forcibly exiled to the Quapaw Agency in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). They were marched thousands of miles, a journey that claimed more lives, and were forced to begin a new life in a foreign land, far from their sacred ancestral home. It would be decades before some of their descendants were allowed to return to their homeland.

The Modoc War and the story of Captain Jack remain a powerful, if painful, reminder of the clash between cultures, the devastating consequences of broken treaties, and the enduring human desire for self-determination. Captain Jack, the reluctant warrior, stands as a complex figure: a leader who sought peace but was driven to violence by circumstance, a master strategist who transformed a desolate landscape into a formidable defense, and ultimately, a tragic symbol of Indigenous resistance against overwhelming odds. His stand in the Lava Beds, though ultimately futile, etched a powerful message into the American consciousness—a message of courage, resilience, and the profound cost of the nation’s expansion. The silence of the Lava Beds today still echoes with the memory of that unyielding stand for home and honor.