Modoc Tribe: Lava Beds History & Cultural Persistence

The stark, volcanic landscape of the Lava Beds National Monument in Northern California is more than just a geological wonder; it is the enduring heartland of the Modoc people, a testament to their profound connection to the land, their fierce struggle for sovereignty, and their remarkable cultural persistence against overwhelming odds. For generations, this labyrinthine terrain, sculpted by ancient eruptions, provided shelter, sustenance, and a sacred identity. It was here, amidst the caves and rugged ridges, that the Modoc made their last, desperate stand, etching their story into the very rock and sky.

The Modoc, who called themselves "Moadoc," meaning "Southern Tule Lake People," had cultivated an intimate relationship with this rugged terrain for millennia. Their lives were meticulously attuned to the seasons, fishing for salmon and trout in the Lost River and Tule Lake, hunting waterfowl, and gathering abundant root vegetables like camas and wapato. The volcanic soil, while seemingly barren to outsiders, provided a bounty understood and managed through generations of ecological knowledge. The caves, formed by ancient lava flows, served as natural shelters from the harsh winters and scorching summers, as well as places of spiritual significance and refuge. This was not merely a dwelling place; it was an integral part of their spiritual and cultural fabric, shaping their worldview, their stories, and their very identity.

The arrival of Euro-American settlers in the mid-19th century shattered this ancient harmony. The lure of gold, fertile lands, and the perceived "empty" wilderness brought an influx of immigrants who saw the land as a resource to be exploited rather than a homeland to be respected. The Modoc, like countless other Indigenous nations, found themselves caught in the inexorable tide of Manifest Destiny. Tensions escalated rapidly as settlers encroached on traditional Modoc territories, leading to violent clashes over resources and land.

In 1864, under duress and facing a superior military force, the Modoc signed a treaty with the U.S. government, ceding much of their ancestral land in exchange for a reservation shared with their traditional rivals, the Klamath, in southern Oregon. This forced cohabitation proved disastrous. The Klamath, who held a numerical advantage and often sided with the agents, viewed the Modoc as interlopers. The Modoc, in turn, found the reservation’s designated lands insufficient and its rules restrictive, especially regarding their traditional hunting and fishing grounds. Disease, starvation, and cultural suppression became the bitter realities of reservation life.

A young Modoc leader named Kintpuash, known to the Americans as Captain Jack, emerged as a vocal advocate for his people’s right to their own land. He argued passionately for a separate Modoc reservation on their traditional lands along the Lost River. When these pleas fell on deaf ears, Captain Jack and a band of his followers, numbering around 150 men, women, and children, defiantly left the Klamath Reservation in 1870, returning to their cherished homeland on the Lost River.

Their peaceful return was short-lived. In November 1872, the U.S. Army, under orders to force the Modoc back to the Klamath Reservation, confronted Captain Jack’s band. A skirmish ensued, and the Modoc, realizing the futility of an open battle, retreated into the familiar sanctuary of the Lava Beds. This marked the beginning of the Modoc War, a conflict that would captivate the nation and expose the brutal realities of America’s expansionist policies.

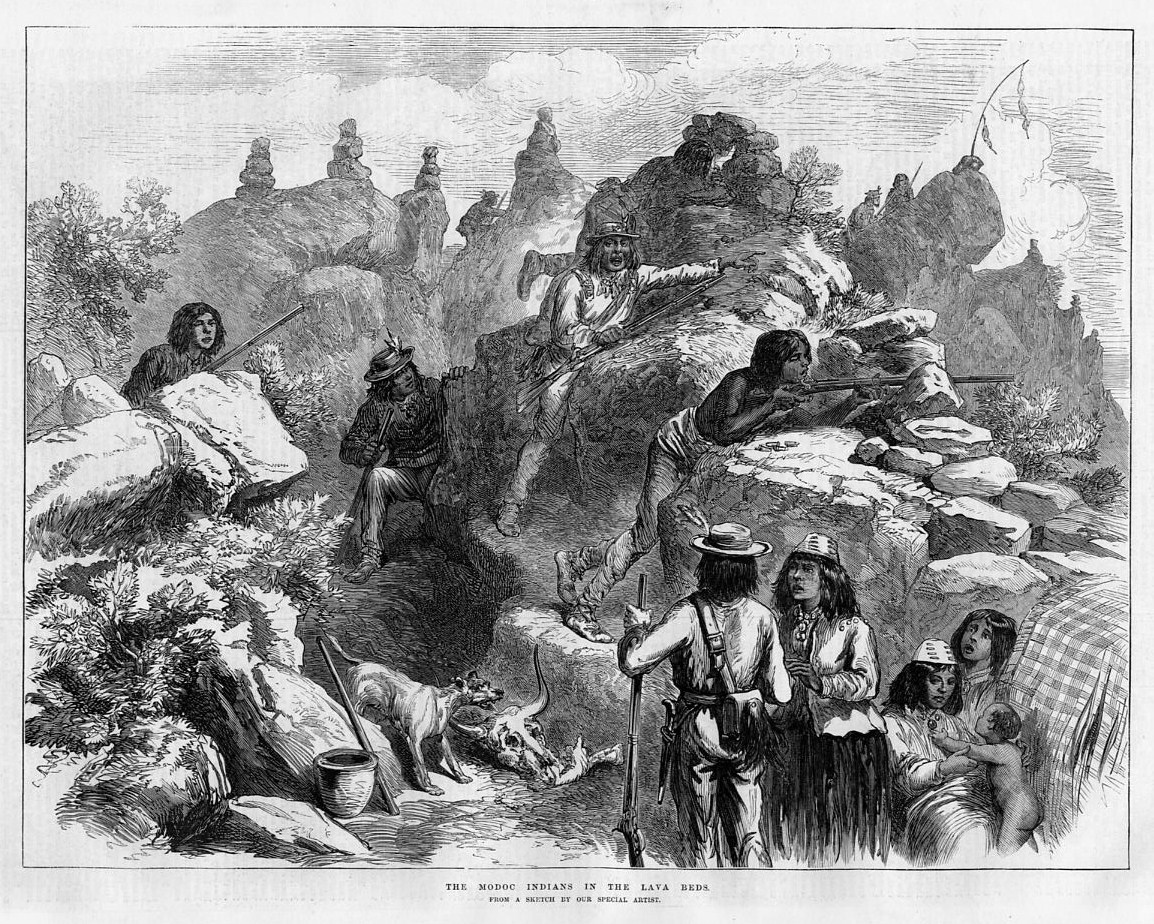

The Lava Beds, with its intricate network of caves, fissures, and rugged terrain, became an impregnable fortress for the Modoc. What seemed like an inhospitable wasteland to the American military was, for the Modoc, a meticulously understood and strategically advantageous homeland. They knew every crevice, every hidden passage, every vantage point. "Captain Jack’s Stronghold," a natural redoubt within the Lava Beds, became the epicenter of their resistance. Here, Modoc warriors, numbering fewer than 60, held off a U.S. Army force that eventually swelled to over 1,000 soldiers, including cavalry, infantry, and artillery, along with Klamath and Warm Springs scouts.

The Modoc’s intimate knowledge of the terrain, combined with their disciplined marksmanship and innovative use of the natural defenses, allowed them to inflict heavy casualties on the better-equipped, but ill-prepared, American troops. The U.S. military suffered humiliating defeats, most notably during the First Battle of the Stronghold in January 1873, and again in April at the so-called "Peace Conference." During this ill-fated meeting, frustrated by the lack of progress and feeling increasingly betrayed, a Modoc faction, against Captain Jack’s initial wishes, ambushed and killed General Edward Canby and Reverend Eleazar Thomas, members of the peace commission. This act, while born of desperation and perceived treachery, sealed the Modoc’s fate in the eyes of the American public and government.

The killing of Canby intensified the military’s resolve. A relentless siege followed, with the army employing increasingly brutal tactics, including cutting off the Modoc’s water supply. Despite their courage, the Modoc’s resources dwindled. Internal divisions began to surface, and some warriors, fearing starvation and total annihilation, eventually surrendered or betrayed Captain Jack. On June 1, 1873, after months of remarkable resistance, Captain Jack and his remaining followers surrendered.

The aftermath was swift and severe. Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Black Jim, and Boston Charley were tried by a military commission for the murder of General Canby and Reverend Thomas. Despite arguments that they acted under duress and in a state of war, they were found guilty and hanged on October 3, 1873, at Fort Klamath. Their bodies were later exhumed and their heads sent to the Army Medical Museum in Washington D.C. for study, a horrific act of desecration that further underscored the dehumanization of Indigenous peoples.

The remaining 153 Modoc men, women, and children were exiled, sent on a forced march thousands of miles across the country to the Quapaw Agency in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This "Modoc Death March" was fraught with hardship, disease, and starvation, claiming many lives along the way. Arriving in Oklahoma, they were a broken, but not defeated, people.

Despite the immense trauma of war, execution, and forced removal, the Modoc people demonstrated extraordinary cultural persistence. In Oklahoma, under the leadership of individuals like Old Schonchin, they slowly rebuilt their community. They adapted to new agricultural practices, learned English, and navigated the complex world of federal Indian policy. Crucially, they held onto their language, their oral traditions, their basketry skills, and their spiritual beliefs. The stories of Captain Jack, the Lava Beds, and their defiant stand became cornerstones of their collective memory, passed down through generations, ensuring that the sacrifices and courage of their ancestors would never be forgotten.

In 1909, after years of tireless advocacy, a small group of Modoc were allowed to return to Oregon. They established a new community near Chiloquin, close to their ancestral lands, and eventually formed the Modoc Nation of Oregon (now the Modoc Tribe of Oregon), which gained federal recognition in 1964. Meanwhile, the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma continued to thrive, maintaining their distinct identity and cultural practices, while always remembering their origins in the Lava Beds.

Today, the Modoc people, represented by two distinct but interconnected tribes in Oklahoma and Oregon, continue to honor their history and heritage. Lava Beds National Monument remains a sacred and deeply significant place. Descendants of the warriors and families who fought there visit the caves and battle sites, not just as tourists, but as pilgrims connecting with their ancestral spirits. The land itself is a living museum, a powerful reminder of their resilience, sacrifice, and the enduring strength of their cultural identity.

The Modoc story is more than a tragic chapter in American history; it is a profound narrative of survival, adaptation, and unwavering connection to a homeland. The Lava Beds, once a symbol of desperate resistance, now stands as a testament to the Modoc’s indomitable spirit and the enduring power of their cultural persistence. It reminds us that even in the face of overwhelming adversity, a people’s spirit, rooted in their land and their traditions, can and will endure. The Modoc’s voice, though once silenced, now resonates across the volcanic plains, telling a story that continues to educate and inspire, ensuring that their history and their profound bond with the Lava Beds are never forgotten.