Echoes of Empire: Unearthing the Complex Societal Structures of the Mississippian Culture

For centuries, the American landscape has held silent testament to a civilization often overlooked in the grand narrative of pre-Columbian America. Long before European footsteps disturbed its ancient earth, a sophisticated culture known as the Mississippian flourished across the fertile river valleys of what is now the southeastern and midwestern United States. From approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, these skilled agriculturalists built monumental earthworks, established vast trade networks, and developed intricate societal structures that rivaled, in complexity and influence, many of their Old World contemporaries. Far from being simple villagers, the Mississippians constructed highly stratified societies, ruled by powerful elites, underpinned by a potent religious cosmology, and sustained by the bounty of their cultivated lands.

At the heart of the Mississippian social order lay the chiefdom, a hierarchical political organization characterized by a ranked society and hereditary leadership. Unlike the more egalitarian tribal structures that preceded them, Mississippian chiefdoms saw power concentrated in the hands of a ruling elite, often a paramount chief, whose authority extended over multiple communities and, in some cases, vast regional networks. These paramount chiefdoms, such as the colossal city of Cahokia near modern-day St. Louis, Missouri, could exert influence over dozens of smaller chiefdoms, demanding tribute, mediating disputes, and coordinating labor for monumental construction projects.

Cahokia: A Metropolis of Power and Prestige

Cahokia stands as the quintessential example of Mississippian societal complexity. At its peak around 1050-1200 CE, it was a sprawling urban center home to an estimated 10,000-20,000 people, making it larger than London at the same time. Its most striking feature, Monk’s Mound, remains the largest prehistoric earthen structure in the Americas, a colossal testament to the organized labor and central authority of the Cahokian elite. This 100-foot-tall, multi-terraced mound served as the ceremonial and political heart of the city, likely topped by a massive temple or the residence of the paramount chief – a visible symbol of divine power and earthly might.

The existence of such a monumental construction project, requiring the movement of millions of cubic feet of earth by hand, speaks volumes about the societal structure. It implies a highly organized command structure capable of mobilizing a vast labor force, overseeing its sustenance, and maintaining social cohesion over generations. This level of coordination could only be achieved through a clear hierarchy and a shared belief system that validated the authority of the leaders.

Social Stratification: Elites, Commoners, and Specialists

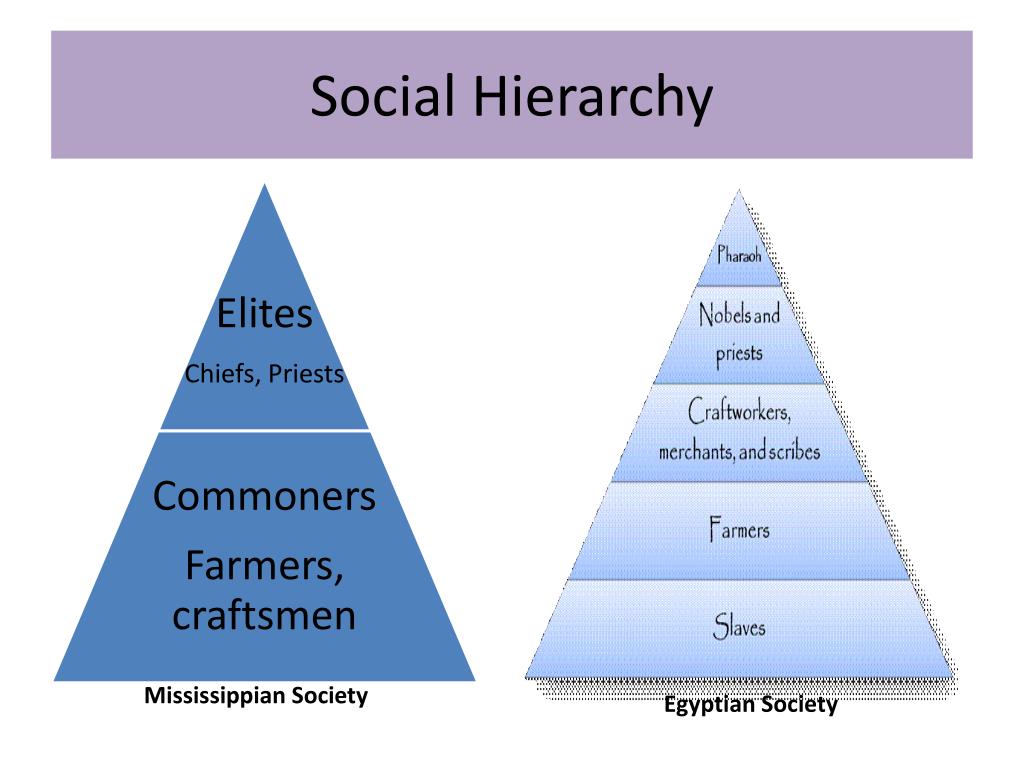

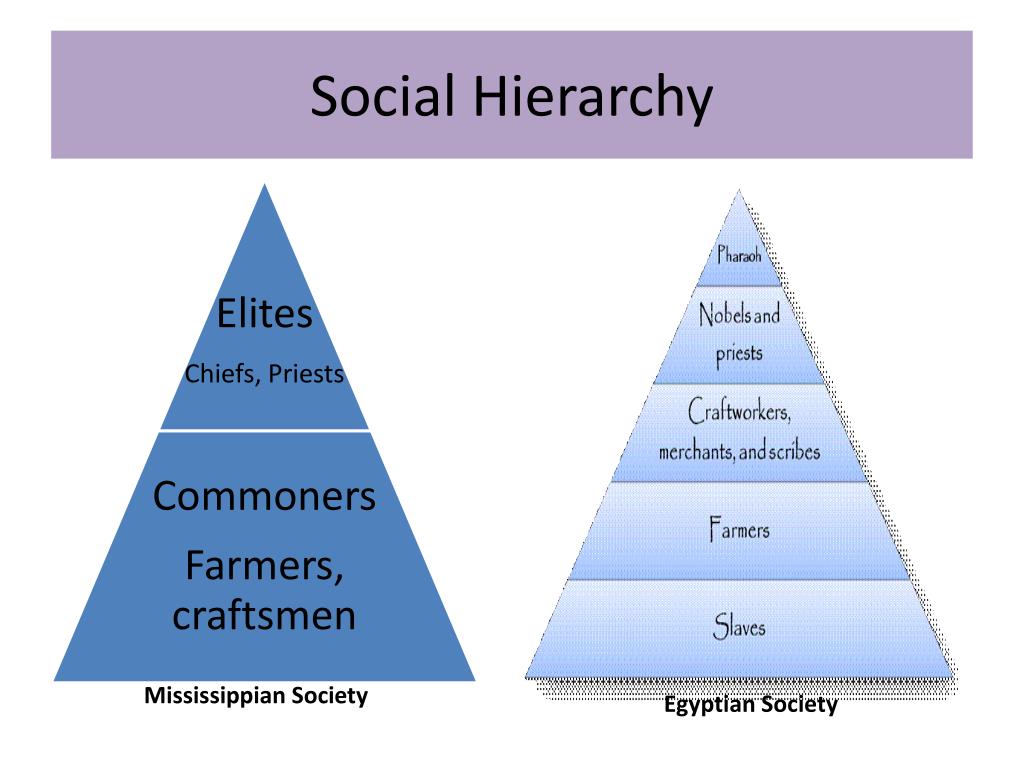

Mississippian society was unequivocally stratified, a stark departure from the more communal arrangements of earlier Woodland cultures. Archaeological evidence, particularly from burial sites and residential patterns, reveals distinct social classes:

-

The Elite: At the apex of Mississippian society were the chiefs and their families, often considered divine or semi-divine, descended from powerful ancestors or linked directly to the cosmos. Their power was both secular and sacred. They resided on top of the principal mounds, in larger, more elaborate homes, physically elevated above the common populace. Their burials were often extravagant, laden with sumptuary goods that signified their status: polished copper plates, intricate shell gorgets, exotic nonlocal materials, and elaborate ceramic vessels.

A fascinating example is the famous "Birdman" burial (Mound 72) at Cahokia. This primary burial contained a man laid upon a platform of 20,000 shell beads, shaped into the form of a falcon (a prominent symbol in Mississippian cosmology). Surrounding him were other burials, including four men with their heads and hands removed, and a mass grave of 53 young women, many showing signs of violent death. This grim tableau suggests ritual sacrifice on a grand scale, underscoring the immense power and sacred authority wielded by the paramount chief, whose death could necessitate such a dramatic ceremony to accompany him into the spirit world. Such elaborate burials served not only as a final resting place but also as a powerful public display of dynastic legitimacy and the immutable social order.

-

The Commoners: The vast majority of the population comprised the commoners, the agricultural backbone of Mississippian society. They lived in smaller, less elaborate dwellings surrounding the ceremonial centers, typically in wattle-and-daub houses. Their lives revolved around subsistence farming, primarily cultivating maize (corn), beans, and squash – the "Three Sisters" – which provided the caloric surplus necessary to support larger populations and specialized labor. Commoners also participated in hunting, fishing, and gathering wild resources.

Their contribution was vital. They provided the labor for mound construction, cultivated the fields that fed the entire population, and contributed to the communal projects that sustained the chiefdom. While their burials were far less elaborate than those of the elite, they often contained utilitarian items or simple adornments, reflecting their daily lives and roles within the community.

-

Specialists and Artisans: Between the ruling elite and the commoners existed a burgeoning class of specialists. The agricultural surplus freed a segment of the population to pursue crafts and services beyond basic subsistence. This included highly skilled artisans who produced the exquisite pottery, carved shell, woven textiles, and hammered copper artifacts that characterize Mississippian culture. These specialized goods were not only symbols of status for the elite but also vital components of regional trade networks.

Priests, warriors, and administrators also constituted specialized roles. Priests played a crucial role in maintaining the religious cosmology that legitimized the chief’s power and ensured the well-being of the community through rituals and ceremonies. Warriors were essential for defense, expansion, and enforcing the chief’s authority, often adorned with symbols of their prowess. The presence of specialized craft workshops and distinct warrior iconography suggests a division of labor that further solidified the stratified nature of these societies.

The Power of Cosmology and Ritual

Religion and cosmology were inextricably interwoven with Mississippian societal structure, serving as a powerful tool for legitimizing elite rule and maintaining social order. The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC), also known as the Southern Cult, refers to a widespread iconography and set of beliefs shared across many Mississippian chiefdoms. Common motifs include the winged or "Birdman" figure, often associated with warfare and celestial power; the Great Serpent or rattlesnake, symbolizing fertility and the underworld; and various sun and fire symbols.

Chiefs were often depicted with these symbols, linking them directly to the divine and cosmic forces. Their authority was not merely political but sacred, positioning them as intermediaries between the earthly realm and the spirit world. Public ceremonies, often held on the plazas fronting the great mounds, reinforced these beliefs, fostering community cohesion while simultaneously highlighting the chief’s central role and divine connection. The cyclical nature of agriculture, dependent on celestial movements, further emphasized the chief’s perceived ability to ensure bountiful harvests through ritual.

Economic Foundations and Regional Networks

The stability and growth of Mississippian chiefdoms were fundamentally rooted in their agricultural prowess. The domestication of maize allowed for a reliable and abundant food supply, which in turn supported denser populations and the specialization of labor. This agricultural surplus also facilitated trade.

Mississippian societies were connected by extensive trade networks, exchanging raw materials and finished goods across vast distances. Copper from the Great Lakes region, marine shells from the Gulf Coast, mica from the Appalachian Mountains, and chert for tools were all transported, sometimes over thousands of miles. This long-distance trade not only enriched the elite with exotic sumptuary goods but also fostered inter-chiefdom relationships, sometimes cooperative, sometimes competitive. The control over these valuable resources and trade routes would have further enhanced the power and prestige of the paramount chiefs.

The End of an Era and Enduring Legacy

By the time European explorers like Hernando de Soto penetrated the Southeast in the 16th century, many Mississippian chiefdoms were already in decline or undergoing significant transformations. The introduction of Old World diseases, against which indigenous populations had no immunity, proved catastrophic, decimating populations and disrupting established social orders. Climate change, resource depletion, and internal conflicts likely also contributed to the eventual fragmentation and collapse of many complex chiefdoms.

While the monumental cities and stratified societies of the Mississippian culture largely faded from memory, their legacy endures. The thousands of earthen mounds scattered across the landscape stand as silent monuments to their ingenuity, organizational capacity, and spiritual depth. Archaeological research continues to peel back the layers of earth and time, revealing a rich and complex tapestry of human experience in pre-Columbian North America. The Mississippian societal structure, with its powerful chiefs, stratified classes, and profound spiritual beliefs, offers a compelling reminder that advanced civilizations, with all their intricate workings and human drama, thrived on this continent long before the arrival of Europeans, challenging simplistic narratives and enriching our understanding of the human capacity for societal organization.