Celestial Weavings: The Profound Tapestry of Navajo Constellations and Astronomy

For the Diné, the Navajo people, the night sky is far more than a distant spectacle of stars; it is a living, breathing guide, a sacred text, and a profound mirror reflecting their worldview of Hózhó – balance, harmony, and beauty. Unlike Western astronomy’s detached scientific inquiry, Navajo celestial knowledge is inextricably woven into the fabric of daily life, ceremony, and moral philosophy. It is a system of understanding that binds the human experience to the cosmos, offering practical guidance, spiritual lessons, and an enduring connection to the ancestors and the future.

The Diné sky is not merely observed; it is engaged with, interpreted, and lived. Every star, every constellation, every celestial phenomenon carries a narrative, a purpose, and a set of instructions for proper living. "The stars are our teachers," notes Dr. Nancy Maryboy, a Cherokee/Navajo scholar and president of the Indigenous Education Institute. "They teach us about our origins, our responsibilities, and our place in the universe. They are a living library of knowledge." This knowledge is not static; it is dynamic, passed down through generations via oral tradition, storytelling, and ceremonial practice, evolving yet remaining anchored in fundamental principles.

From calendrical reckoning to agricultural cycles, the stars provided a precise, natural clock for the Diné. The appearance and disappearance of specific constellations dictated the timing for planting maize, harvesting crops, hunting seasons, and the commencement of sacred ceremonies. Navigators, hunters, and travelers found their bearings beneath the vast, star-strewn canopy of the Navajo Nation, using the celestial patterns as an infallible map across their ancestral lands. The movement of the sun, moon, and stars also informed weather predictions, enabling communities to prepare for seasonal changes and potential challenges.

Beyond the practical, the celestial bodies serve as enduring repositories of Diné philosophical and ethical teachings. Creation stories are etched in the starlight, recounting the formation of the world and the emergence of the Diné. Constellations are often personified, acting as characters in these narratives, demonstrating virtues like resilience, cooperation, and respect, or cautionary tales of arrogance and imbalance. The entire celestial sphere is seen as a manifestation of the Holy People (Diyin Diné’e), whose actions and forms provide a moral compass for humanity.

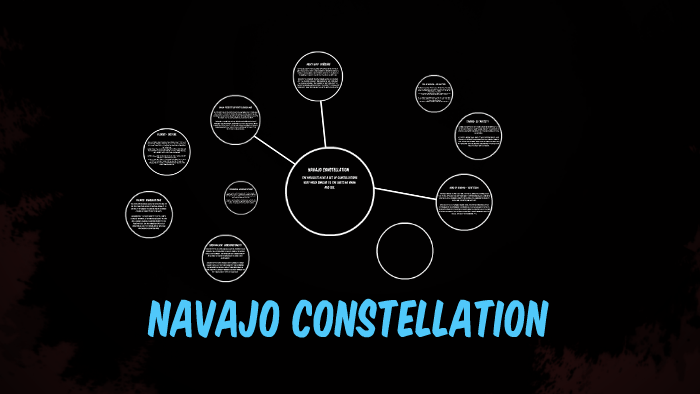

Among the most revered and foundational celestial formations is Dilyéhé, the Pleiades. Known as the "First Star," Dilyéhé holds immense significance as a harbinger of new beginnings and a symbol of renewal. Its heliacal rising – its first appearance above the eastern horizon at dawn – traditionally marked the start of the Navajo year and the appropriate time to begin planting maize. When Dilyéhé is visible in the evening sky, it signals a period of growth and activity; its disappearance below the western horizon at dusk marks a time for rest, storytelling, and the cessation of planting. Dilyéhé is often associated with the male principle, representing order, leadership, and the careful planning required for a successful season. Its presence in the sky reminds the Diné of their cyclical relationship with the earth and the importance of precise timing and diligent effort.

Náhookǫs, meaning "the Revolving One," encompasses the stars of the Big Dipper. This prominent constellation is fundamental for navigation, as it always points towards the North Star, Polaris. For the Diné, Náhookǫs is often divided into two primary figures: Náhookǫs Bikąʼí (the Male Revolving One, or the "Big Dipper") and Náhookǫs Bi’áád (the Female Revolving One, or Cassiopeia). Together, they represent a balanced male and female partnership, symbolizing community, family, and the protection of the home. The stars within Náhookǫs are also seen as guardians, watching over the Diné and guiding them on their journeys. The ladle of the Big Dipper, in particular, is sometimes interpreted as a campfire, with the stars representing a family gathered around it, emphasizing the importance of warmth, kinship, and shared wisdom. The constant revolution of Náhookǫs around Polaris also speaks to the enduring nature of Diné traditions and their steadfast connection to their homeland.

The powerful constellation of Orion is known to the Diné as Átse Etso, "First Big One" or "Giant Warrior." Átse Etso is often depicted as a strong, formidable figure, sometimes associated with hunting prowess and the pursuit of sustenance. In some narratives, he is seen as a protector, while in others, he represents the challenges and struggles that must be overcome. His presence in the winter sky, a time of scarcity, serves as a reminder of the need for courage, resourcefulness, and the strategic planning required to survive and thrive. Átse Etso’s prominent belt stars are particularly significant, often marking the center of his power and influence. His stories often teach lessons about strength, endurance, and the consequences of one’s actions.

The majestic sweep of the Milky Way, Yikáísdáhá – "that which awaits the dawn" or "the path where the spirits walk" – is another profoundly significant celestial feature. This luminous band across the night sky is often understood as a spiritual pathway, a road for the spirits of the deceased as they journey to the afterlife or return to the Holy People. It symbolizes the continuity of life and death, the connection between the earthly realm and the spiritual realm. Yikáísdáhá is also seen as a representation of balance and interconnectedness within the cosmos. Its diffuse light is often contrasted with the sharp points of individual stars, suggesting a broader, unifying force that holds the universe together. The Diné are taught to respect this sacred path and to live in a way that honors the ancestors who have walked it before them.

This intricate astronomical knowledge is not found in textbooks but is embedded within the rich oral tradition of the Diné. Elders pass down stories to younger generations, often under the very stars being discussed. These storytelling sessions are not merely entertainment; they are immersive educational experiences where lessons in ethics, history, ecology, and astronomy are intertwined. The absence of a written tradition for much of this knowledge underscores its sacred nature and the emphasis on direct, intergenerational learning. The act of sharing these stories reinforces community bonds and ensures the continuity of Diné identity.

The fundamental divergence from Western astronomy lies in purpose and perspective. While Western science seeks to quantify, categorize, and understand the physical mechanisms of the universe, Diné astronomy seeks to understand the meaning and relationship of the cosmos to human existence. It is not about discovering distant galaxies for their own sake, but about discerning the lessons they hold for living a life of Hózhó. The sky is not an object of detached study; it is an active participant in Diné life, a relative, a teacher, a guide.

Despite its profound significance, Diné astronomy faces contemporary challenges. Light pollution from growing urban centers encroaches upon the pristine dark skies that were once ubiquitous across the Navajo Nation, obscuring the very stars that hold so much cultural weight. The decline of the Navajo language among younger generations also poses a threat, as the stories and specific terminology associated with celestial knowledge are often lost in translation or simply not transmitted. Urbanization and a disconnect from traditional land-based practices can further erode the direct, experiential learning that is crucial for internalizing this knowledge.

Yet, there is a powerful movement within the Navajo Nation to preserve and revitalize this sacred knowledge. Cultural centers, educational programs, and dedicated scholars are working to document, teach, and share Diné astronomy, ensuring its survival for future generations. Initiatives to combat light pollution and establish dark sky reserves are gaining traction, recognizing that the ability to see the stars clearly is not just an aesthetic pleasure but a cultural imperative. These efforts underscore the understanding that Diné astronomy is not merely a historical curiosity, but a living, breathing system of knowledge that offers profound insights into what it means to be human and to live in harmony with the vast universe around us.

The Navajo night sky remains a potent symbol of enduring cultural identity and a profound testament to a people who have long understood that true wisdom lies not just in observing the stars, but in living in harmony with their timeless narratives. It is a reminder that the universe is not a cold, empty void, but a vibrant tapestry of meaning, guidance, and spiritual connection, constantly unfolding above us, waiting to teach those who are willing to listen.