The Earth’s Embrace and the Soil’s Bounty: The Enduring Legacy of the Mandan Tribe

Along the vast, winding expanse of the Missouri River, where the Great Plains begin their gentle undulation towards the west, a civilization flourished for centuries, defying the nomadic stereotype often assigned to Plains Indigenous peoples. This was the domain of the Mandan Tribe, renowned not for their equestrian prowess in buffalo hunts, though they were adept, but for their rootedness: sophisticated earth lodge builders and masterful agriculturalists whose traditions shaped the very landscape and culture of the Northern Plains. Their story is one of innovation, resilience, profound spiritual connection to the land, and an enduring legacy that continues to resonate today.

From their earliest known settlements, dating back over a thousand years, the Mandan people carved out a unique existence. Unlike their nomadic neighbors who followed the buffalo herds, the Mandan built permanent, fortified villages, often strategically located on bluffs overlooking the Missouri, its tributaries, and their fertile bottomlands. These villages were bustling centers of life, trade, and ceremony, housing hundreds, sometimes thousands, of individuals. At the heart of these communities stood their iconic earth lodges – architectural marvels that were as functional as they were symbolic.

The Earth Lodge: An Architectural Masterpiece

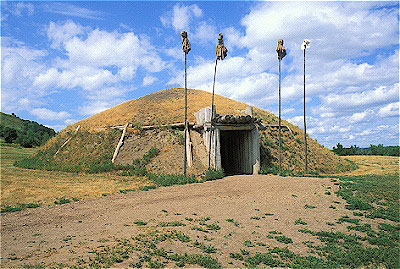

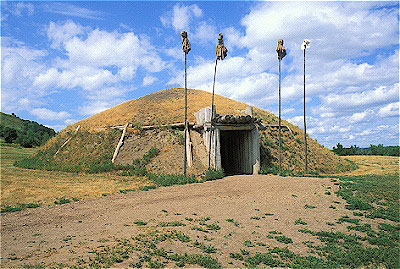

The Mandan earth lodge, or numak-mahana, was far more than a simple dwelling; it was a microcosm of their world, ingeniously designed to withstand the extremes of the Plains climate. These substantial, dome-shaped structures, typically ranging from 30 to 60 feet in diameter, were built with a robust framework of heavy timber posts and rafters, carefully selected and hauled from riverine forests. These timbers were then covered with a thick layering of willow branches, grass, and finally, several feet of packed earth and sod. This ingenious construction created a remarkably insulated dwelling: warm in the brutal Dakotan winters and refreshingly cool during the scorching summers.

Entry was typically through a long, covered passageway, designed to minimize heat loss or gain. Inside, a central fire pit provided warmth and light, with a smoke hole at the apex of the dome allowing ventilation. Around the perimeter, raised platforms served as sleeping areas, often adorned with woven mats and buffalo robes. Each lodge housed an extended family, embodying the communal spirit of Mandan society. As Meriwether Lewis, co-leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, observed in 1804-1805 during their winter encampment near a Mandan village, these lodges were "well calculated to stand the test of time, and capable of containing a large family." He further noted their impressive construction and the orderliness within. The earth lodge was not merely shelter; it was a sacred space, often viewed as representing the universe, with the central fire symbolizing the sun and the earth covering connecting them deeply to the land from which they drew their sustenance.

The Agricultural Heartbeat: Sustenance, Sacredness, and Sophistication

While the earth lodges anchored their physical presence, it was their sophisticated agricultural traditions that truly defined the Mandan way of life and ensured their prosperity. The rich, alluvial soils of the Missouri River bottomlands proved ideal for cultivation, and the Mandan developed highly effective farming techniques that were the envy of many surrounding tribes. Their primary crops, often referred to as the "Three Sisters," were corn (maize), beans, and squash – a mutually beneficial planting strategy where corn stalks provided a trellis for climbing beans, and squash plants spread across the ground, shading out weeds and retaining soil moisture.

Mandan women were the primary cultivators, holding significant economic and social power within the tribe due to their vital role in food production. Their farming was a meticulous process: planting in the spring after the ground thawed, careful tending throughout the growing season, and a communal harvest in late summer and early fall. They cultivated a variety of corn strains, including the distinctive Mandan Red Flour Corn, prized for its flour-making qualities. Beyond the Three Sisters, they also grew sunflowers for oil and seeds, and tobacco for ceremonial purposes.

The bounty of their harvests was impressive. After drying and processing, much of the surplus was stored in ingeniously designed subterranean cache pits – bell-shaped excavations lined with grass, located both inside and outside the lodges. These pits kept the produce cool, dry, and protected from rodents and spoilage, allowing the Mandan to sustain themselves through the harsh winters and providing a valuable commodity for trade. This agricultural surplus, combined with their skills in hunting buffalo and other game, created a diverse and stable diet, ensuring a level of security rarely achieved by purely nomadic groups.

The spiritual dimension of their agriculture cannot be overstated. Planting, growth, and harvest were imbued with deep religious significance, celebrated through elaborate ceremonies and rituals that honored Mother Earth and the spirits responsible for fertility and abundance. The corn was not just food; it was a sacred gift, central to their identity and worldview.

A Riverine Civilization: Trade, Diplomacy, and Interconnectedness

The Mandan’s strategic location on the Missouri River, coupled with their agricultural wealth, positioned them as a central hub of trade and diplomacy across the Northern Plains. The Missouri served as an ancient highway, connecting disparate tribes and facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas over vast distances. Mandan villages became bustling marketplaces where they traded their prized agricultural products – corn, beans, squash, and sunflower oil – along with finely tanned buffalo hides, pottery, and crafted goods.

In return, they acquired a diverse array of items: obsidian and other stone for tools from the Rocky Mountains, pipestone from Minnesota, horses from the Western Plains tribes, and later, European manufactured goods such as metal tools, firearms, and glass beads from traders traveling upriver. Their role as intermediaries in these extensive trade networks brought them wealth, influence, and exposure to various cultures, fostering a sophisticated understanding of regional politics and intertribal relations. Their close alliances with the Hidatsa and later the Arikara, forming what would become known as the Three Affiliated Tribes, further cemented their position as a formidable power in the region.

Encounters and Transformations: The Shadow of Smallpox

The early 19th century marked a pivotal and tragic turning point for the Mandan. The winter of 1804-1805 saw the arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, who built Fort Mandan adjacent to their villages. This encounter provided one of the most detailed early accounts of Mandan life, describing a thriving, hospitable, and well-organized society. Lewis estimated their population at around 1,500 people, spread across two large villages, and found them remarkably open and generous.

However, contact with Europeans, while initially bringing new trade goods, also introduced an insidious and far more devastating force: disease. The Mandan, like many Indigenous peoples across the Americas, had no natural immunity to Old World pathogens. The smallpox epidemic of 1837-1838 proved catastrophic. Carried up the Missouri by American fur traders, the disease swept through their villages with horrifying speed and lethality. Within a few months, the Mandan population was decimated, plummeting from an estimated 1,600 to barely 100-150 survivors. Entire families, lineages, and vast repositories of traditional knowledge were wiped out. The once-thriving villages became silent, haunting monuments to a lost world.

This demographic collapse was not just a numbers game; it was a profound cultural trauma. The Mandan were forced to abandon their ancestral villages and consolidate with their Hidatsa and Arikara allies, their independent existence irrevocably altered. Yet, even in the face of such unimaginable loss, the Mandan spirit of resilience endured.

Cultural Resilience and Enduring Legacy

The survival of the Mandan people after the 1837 epidemic is a testament to their strength and adaptability. They rebuilt their lives alongside the Hidatsa and Arikara, forming the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation) on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. This alliance, born of necessity, forged a new collective identity while striving to maintain individual cultural distinctiveness.

Today, the Mandan continue to honor their heritage. Efforts are underway to revitalize the Mandan language, which is critically endangered, and to teach younger generations the traditional stories, ceremonies, and practices. Their agricultural traditions, particularly the cultivation of heirloom corn varieties like the Mandan Red Flour Corn, are experiencing a resurgence, connecting them directly to their ancestors and promoting food sovereignty. The earth lodge, though no longer a primary dwelling, remains a powerful symbol of their enduring connection to the land and their architectural ingenuity. Reconstructions, such as the one at the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, serve as poignant reminders of their rich past and a testament to their legacy as sophisticated builders and cultivators.

The Mandan Tribe stands as a powerful counter-narrative to simplistic portrayals of Plains Indigenous peoples. They were not merely buffalo hunters but master builders, innovative farmers, savvy traders, and resilient survivors. Their story is a crucial chapter in the history of North America, showcasing how deep knowledge of the land, coupled with ingenuity and community spirit, can forge a vibrant civilization. From the deep embrace of their earth lodges to the rich bounty of their cultivated fields, the Mandan’s legacy is one of profound connection to the Missouri River and an unwavering commitment to a way of life deeply rooted in the earth’s enduring promise. Their journey, marked by both triumph and tragedy, serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring strength of Indigenous cultures and their invaluable contributions to the tapestry of human history.