Echoes of Thunder: The Mandan Tribal Renewal and the Sacred Call of the Buffalo

On the vast, windswept plains of what is now North Dakota, where the Missouri River carves its ancient path, a people known as the Mandan once thrived. They were master agriculturists, dwelling in ingenious earth lodges, their lives interwoven with the rhythm of the seasons and the monumental presence of the American bison. More than mere sustenance, the buffalo was the lifeblood, the spiritual anchor, and the very embodiment of their existence. To ensure its return, to renew their world, the Mandan engaged in profound and arduous rituals, chief among them the intricate dance of tribal renewal and the sacred, life-giving ceremony of Buffalo Calling.

For centuries, before the arrival of European explorers and the devastating march of disease, the Mandan, often in close alliance with the Hidatsa and Arikara tribes, cultivated corn, beans, and squash along the fertile riverbanks. Yet, their agricultural prowess alone could not sustain them through the harsh northern winters. The bison, or buffalo, provided not just meat for food, but also hides for clothing and shelter, bones for tools, sinew for thread, and dung for fuel. It was a relationship of profound reciprocity, a covenant between humanity and the natural world, upheld by spiritual observance and deep respect.

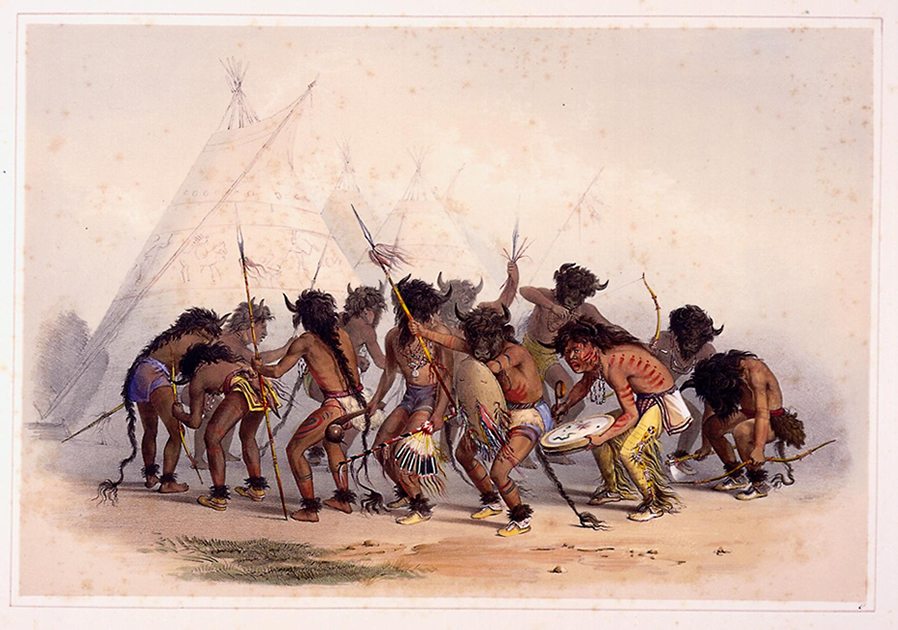

The Mandan’s annual cycle was punctuated by a series of ceremonies designed to maintain cosmic balance, purify the community, and ensure the continuation of life. Central to this was a comprehensive renewal ritual, often referred to by early observers like artist George Catlin as the Okipa ceremony, though buffalo calling could also exist as a distinct, yet interconnected, ritual. While the Okipa itself encompassed a broader range of renewal and initiation, the spirit of buffalo calling was deeply embedded within the Mandan’s spiritual framework for abundance. These rituals were not mere prayers; they were enactments, a living theatre of spiritual appeal and physical endurance, designed to draw the vast herds of buffalo back to their hunting grounds.

Imagine the scene: a specially constructed ceremonial lodge, its interior steeped in the scent of sacred smoke and anticipation. Elders, often holy men or shamans, would lead the proceedings, their faces painted with symbolic designs, adorned with buffalo horn headdresses – potent symbols of the animal’s power and spirit. The air would thicken with the rhythmic thud of drums, the haunting chants, and the shuffle of moccasined feet. The ritual would stretch over days, demanding immense physical and spiritual fortitude from its participants. Fasting was common, a means of purification and opening oneself to the spiritual realm. Dancers, often young men embodying the buffalo itself, would move with a primal grace, mimicking the animal’s movements, its snorts, its charges.

The essence of the Buffalo Calling ritual was an act of profound empathy and spiritual identification. It was believed that through these performances, the Mandan could communicate directly with the spirit world of the buffalo, persuading the herds to offer themselves for the survival of the people. "We would dance for days, our bodies aching, our voices hoarse, but our spirits soaring," recounted a Mandan elder in a historical account. "We were not just asking the buffalo to come; we were becoming the buffalo, calling to our brothers and sisters to join us, to renew our covenant."

Specific elements of the ritual were meticulously observed. Sacred pipes, filled with tobacco, would be offered to the four cardinal directions, to the sky, and to the earth, acknowledging the interconnectedness of all creation. Prayers would be uttered not just for the buffalo, but for the health of the community, for fertile crops, and for peace. The Buffalo Dance, a crucial component, saw participants adorned with buffalo skins and heads, moving in a circular pattern, mimicking the stampede, the grazing, the very essence of the herd. These were not simply performances; they were acts of spiritual transformation, blurring the lines between human and animal, between the mundane and the sacred.

One of the most striking aspects of these renewal rituals, as documented by Catlin in the 1830s, involved extreme tests of endurance and self-sacrifice. While these were part of the broader Okipa and not exclusively for buffalo calling, they highlight the Mandan’s deep commitment to spiritual renewal. Young men would undergo elaborate ordeals, including fasting, sleep deprivation, and even hanging from the lodge’s roof by skewers inserted into their chest and back muscles, their bodies suspended in agony until they collapsed. These acts were not punitive but transformative – a sacred offering to the Great Spirit, a purification, and a demonstration of their unwavering devotion to their people’s well-being and the continuation of life, including the buffalo’s return. It was believed that through such sacrifice, the balance was restored, and the blessings of the Creator, including abundant game, would be bestowed.

The symbolism within these rituals was rich and multilayered. The earth lodge itself, a microcosm of the universe, with its central fire representing the sun, was a sacred space. The buffalo horn headdresses symbolized strength, virility, and the life-giving power of the animal. Body paint, specific songs, and the precise choreography of the dances all carried ancestral meaning, passed down through generations. "Every step, every drumbeat, every whisper carried the stories of our ancestors, the wisdom of the earth, and the fervent hope for our future," a tribal historian might explain. "It was a living prayer, a promise to the buffalo that we would honor their sacrifice."

The profound significance of these rituals extended far beyond the practical need for food. They reinforced community bonds, transmitting cultural knowledge, spiritual values, and a deep ecological understanding to younger generations. They taught respect for all living things, the importance of reciprocity, and the intricate web of life. The Buffalo Calling ceremony was a powerful reaffirmation of Mandan identity, a declaration of their place in the cosmos, and a testament to their spiritual resilience.

However, this sacred way of life faced an existential threat. The Mandan were tragically decimated by a smallpox epidemic in 1837, which reduced their population from an estimated 1,600 to barely over 100 within a few months. This catastrophe, coupled with the relentless westward expansion of European settlers, the systematic slaughter of the buffalo herds, and the imposition of the reservation system, fractured the traditional lifeways. The buffalo, once numbering in the tens of millions, were brought to the brink of extinction, eradicating the very subject of the Mandan’s most vital ceremonies. With their lands shrinking, their population decimated, and their cultural practices suppressed, the elaborate public rituals of renewal and buffalo calling faded, becoming whispers in the collective memory, held fiercely by a dwindling number of elders.

Yet, the spirit of the Mandan, like the buffalo itself, proved remarkably resilient. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, there has been a powerful resurgence of interest and dedication to cultural revitalization among the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nations (now united as the Three Affiliated Tribes). While the grand public ceremonies like those described by Catlin may not be replicated in their exact historical form, the underlying principles of renewal, community, and respect for the buffalo remain profoundly relevant.

Today, tribal councils and cultural preservationists work tirelessly to recover and teach the traditional Mandan language, arts, and ceremonies. Elders share oral histories, young people participate in educational programs, and the sacred connection to the land and the buffalo is being re-established through efforts like buffalo reintroduction programs on tribal lands. The contemporary "buffalo calling" may manifest as diligent ecological stewardship, the pursuit of self-determination, and the unwavering commitment to cultural continuity.

"Our ancestors faced unimaginable hardship, but they never forgot who they were, or their sacred connection to the buffalo," says a modern tribal leader. "Today, our renewal ritual is in teaching our children our language, in bringing back the buffalo to our lands, and in ensuring that the stories and wisdom of those ancient dances continue to echo through the generations. We call not just for the buffalo, but for the strength of our people, for the renewal of our spirit."

The Mandan Tribal Renewal and the Sacred Call of the Buffalo are more than historical curiosities; they are a testament to the enduring human spirit, a powerful narrative of survival, and a profound reminder of the intricate and sacred relationship that once existed – and is being rekindled – between humanity and the natural world. In the whispers of the plains, in the thunder of re-emerging herds, and in the hearts of the Mandan people, the ancient call continues to resonate, a timeless plea for balance, abundance, and the eternal cycle of life.