Guardians of Memory: Unearthing Turtle Island’s Deep History in Library Collections

Turtle Island, the Indigenous name for North America, cradles a history far deeper and more intricate than mainstream narratives often suggest. It is a story told not just in written texts, but in oral traditions, sacred objects, intricate maps, and the very land itself. For centuries, this profound historical tapestry faced erasure, suppression, and misrepresentation. Today, however, libraries, archives, and cultural institutions across the continent are playing an increasingly vital role in reclaiming, preserving, and making accessible the rich and complex history of Turtle Island’s Indigenous peoples. These collections are not mere repositories of the past; they are active sites of cultural revitalization, reconciliation, and the ongoing assertion of Indigenous sovereignty and knowledge.

The scope of "Turtle Island history" is immense, encompassing millennia of pre-contact civilizations, the profound transformations wrought by European arrival, the harrowing eras of colonialism, forced assimilation, and resistance, and the vibrant contemporary movements for self-determination and cultural renewal. To truly grasp this history requires looking beyond singular, often colonial, perspectives and engaging with a multitude of voices and forms of documentation. Libraries, from academic powerhouses to modest tribal archives, are at the forefront of this crucial endeavor.

Diverse Forms of Knowledge: Beyond the Written Word

A central tenet of understanding Turtle Island’s history is recognizing the diverse formats in which knowledge has been preserved. While written documents—treaties, government reports, missionary accounts, anthropological studies—form a significant part of collections, they often represent a colonial gaze. Modern library collections strive to balance and contextualize these with Indigenous-generated materials and epistemologies.

One of the most powerful and historically significant forms of Indigenous knowledge is oral tradition. For countless generations, stories, laws, ceremonies, and historical accounts were passed down verbatim, often with extraordinary fidelity, through elders, storytellers, and ceremonial practitioners. Libraries are increasingly recognizing the imperative to collect, digitize, and ethically steward these invaluable oral histories. Projects like those at the University of British Columbia’s Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, or the Oklahoma Oral History Research Program at Oklahoma State University, record survivor testimonies and community narratives, offering crucial firsthand accounts that challenge official records and provide invaluable insights into the human experience of historical events. The digital age allows these narratives to be preserved and accessed in ways previously impossible, ensuring their continued resonance.

Beyond oral histories, collections encompass a wide array of materials:

- Archival Documents: Treaties (often complex and contested legal documents), land claims, government correspondence, personal papers of Indigenous leaders, activists, and families.

- Photographs and Visual Media: Images documenting daily life, ceremonies, residential schools, protests, and cultural events. These are powerful tools for historical memory and understanding, though often imbued with colonial gazes that require critical interpretation.

- Maps and Geographical Information: Indigenous mapping traditions, often expressing deep connections to land and territory, alongside colonial maps that illustrate shifting power dynamics and land dispossession.

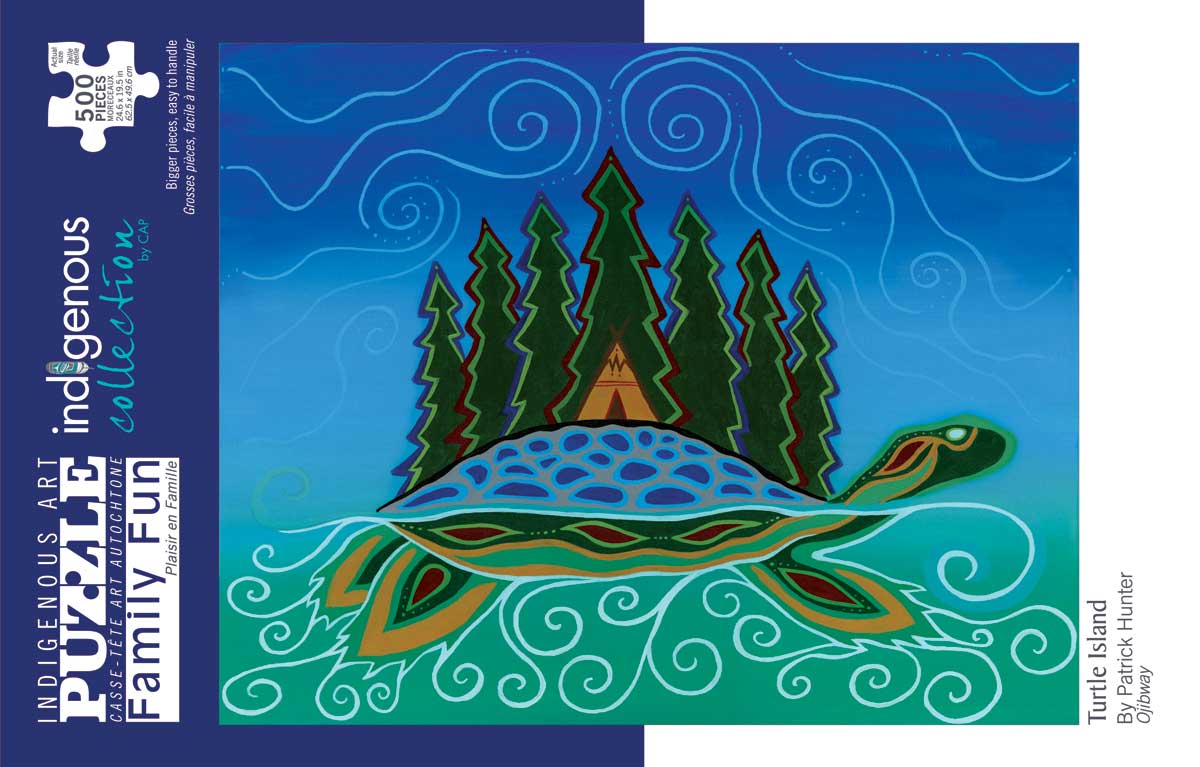

- Art and Material Culture: While often housed in museums, libraries increasingly acquire images and documentation of cultural objects, traditional arts, and contemporary Indigenous art, recognizing their role as historical records and expressions of identity.

- Linguistic Resources: Dictionaries, grammars, language learning materials, and recordings are vital for the preservation and revitalization of Indigenous languages, each a unique repository of cultural knowledge.

- Published Works: Books, journals, and articles by Indigenous authors, scholars, and poets, offering perspectives that are self-determined and culturally grounded.

Key Institutions and Their Contributions

Academic libraries, with their extensive resources and research mandates, often house some of the largest and most comprehensive collections related to Turtle Island history. Institutions like the University of Oklahoma’s Western History Collections, the Newberry Library in Chicago, the American Philosophical Society, and Harvard University’s Peabody Museum Archives hold vast quantities of early documents, ethnographies, and historical records. However, the ethical implications of these historical collections, often amassed through colonial means, are increasingly being scrutinized. Libraries are actively engaging in conversations about repatriation, respectful access, and collaborative stewardship with Indigenous communities.

Public libraries, while often having more generalized collections, play a critical role in community engagement and making Indigenous history accessible to broader audiences. They curate local history collections, host educational programs, and collaborate with Indigenous community groups to ensure their collections reflect local Indigenous narratives. The Toronto Public Library, for instance, has developed extensive Indigenous literature collections and programming, reflecting the diverse urban Indigenous population it serves.

Perhaps most critically, tribal libraries, archives, and cultural centers are emerging as the most important sites for Indigenous historical preservation. These institutions are rooted in the communities they serve, governed by Indigenous leadership, and focused on cultural relevance and sovereignty. They prioritize the collection of local history, family genealogies, language materials, and oral traditions, often in formats and with metadata systems that reflect Indigenous worldviews. The National Museum of the American Indian (part of the Smithsonian Institution) and various tribal colleges and universities also maintain significant archives, acting as vital centers for Indigenous-led scholarship and cultural preservation. These institutions embody the principle of "nothing about us without us," ensuring that history is told from within Indigenous communities.

Challenges and Ethical Imperatives: Decolonizing the Archive

The journey to adequately represent Turtle Island’s history in library collections is fraught with challenges, many stemming from the colonial legacy itself.

- Colonial Bias and Gaps: Many foundational collections were created by non-Indigenous researchers, missionaries, and government officials, often reflecting biases, misunderstandings, and outright misrepresentations. There are significant gaps in records where Indigenous voices were silenced, ignored, or simply not recorded.

- Access and Ownership: Historical practices often saw Indigenous cultural materials removed from their communities, stored in distant institutions, and made inaccessible. The concept of "ownership, control, access, and possession" (OCAP®) for First Nations data, developed by the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) in Canada, provides a framework for ethical data management that respects Indigenous sovereignty. Libraries are increasingly adopting such principles, moving towards collaborative agreements that prioritize Indigenous communities’ rights to their own heritage.

- Fragility and Preservation: Many invaluable historical materials, particularly oral histories and early documents, are fragile and susceptible to decay. Digital preservation is a critical tool, but it requires significant resources and technical expertise.

- Language Barriers: Much of the historical record, both colonial and Indigenous, exists in languages that are not widely understood today. The decline of Indigenous languages poses a significant threat to accessing and interpreting these materials. Libraries are partnering with language revitalization programs to address this.

- Metadata and Description: Traditional library cataloging systems (like Library of Congress Subject Headings) often contain outdated, offensive, or inaccurate terminology for Indigenous peoples and cultures. Decolonizing metadata is an ongoing, crucial task, involving collaboration with Indigenous communities to develop culturally appropriate descriptions and access points. The Homosaurus, a vocabulary of LGBTQIA+ terms, and efforts to revise LCSH are examples of this critical work.

Innovations and the Path Forward

Despite the challenges, significant progress is being made. Digital humanities projects are transforming access, allowing researchers and community members worldwide to explore digitized collections. Platforms like Mukurtu CMS (mukurtu.org) offer community-controlled digital archiving solutions, empowering Indigenous communities to manage their own cultural heritage online, setting access permissions based on cultural protocols.

The field of Indigenous librarianship is growing, bringing Indigenous perspectives and expertise directly into the profession. Indigenous librarians are advocates for ethical stewardship, cultural sensitivity, and community engagement, ensuring that collections are built and managed in ways that truly serve Indigenous peoples. Their work is pivotal in shaping future collections and practices.

Ultimately, library collections on Turtle Island history are more than just archives; they are active instruments of education, reconciliation, and cultural revitalization. They provide the evidence base for land claims, inform language revitalization efforts, inspire contemporary artists and storytellers, and challenge dominant historical narratives. By actively engaging with Indigenous communities, adopting ethical frameworks, and continuously striving to decolonize their practices, libraries are becoming essential partners in ensuring that the rich, complex, and enduring history of Turtle Island is not only preserved but understood, celebrated, and made relevant for generations to come. The quiet hum of a library server or the rustle of an ancient document now carry the powerful echoes of a resilient past, illuminating a path towards a more just and informed future.