The Enduring Legacy of the Lenape: Original People of the Eastern Woodlands

Before the skyscrapers pierced the clouds over Manhattan, before the sprawling metropolises of Philadelphia and Trenton rose from the earth, and long before the names "New York," "Pennsylvania," or "Delaware" were ever uttered, there was Lenapehoking. This vast and fertile land, stretching from the western banks of the Hudson River through the Delaware River Valley and into parts of present-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New York, was the ancestral home of the Lenape, the Original People of the Eastern Woodlands. Their story is one of deep connection to the land, sophisticated societal structure, profound resilience, and an enduring spirit that continues to shape the cultural landscape of North America.

The Lenape, an Algonquian-speaking people, were not a monolithic entity but rather a collection of closely related, politically autonomous groups or "nations," each inhabiting specific territories within Lenapehoking. Anthropologists and historians often categorize them into three main dialect groups, named after the primary rivers they inhabited: the Munsee (upriver, near the Hudson and upper Delaware), the Unami (middle, central Delaware Valley), and the Unalachtigo (downriver, lower Delaware and coastal areas). These divisions, while fluid, reflected subtle linguistic and cultural differences, yet all shared a common heritage, worldview, and an intricate network of kinship and trade.

Their name, "Lenape," translates to "The People" or "Original People," a testament to their deep-rooted identity as the first inhabitants of their cherished lands. They were also often referred to as "Grandfathers" by other Algonquian and Iroquoian tribes, signifying their respected status as ancient and foundational. This respect was earned through their long history, their peaceful demeanor, and their role as mediators in inter-tribal disputes.

Life in pre-contact Lenapehoking was a masterclass in sustainable living and seasonal adaptation. The Lenape were skilled hunter-gatherers and accomplished agriculturalists. Their villages, often situated along rivers and streams, were semi-permanent, reflecting their seasonal migration patterns. During warmer months, they cultivated extensive fields of "the Three Sisters"—corn, beans, and squash—which provided the caloric backbone of their diet. Women were primarily responsible for farming, gathering wild plants, berries, nuts, and medicinal herbs, and preparing food. Men focused on hunting deer, bear, turkey, and smaller game, as well as fishing the abundant waters for sturgeon, shad, and shellfish.

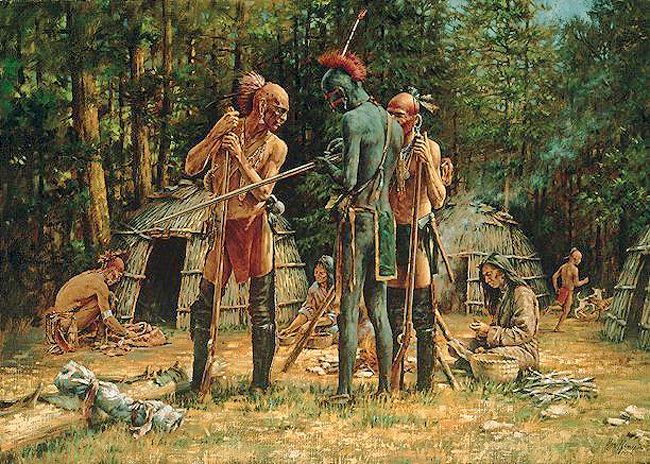

Their dwellings varied with the seasons. Permanent villages featured longhouses, multi-family structures made of saplings and bark, capable of housing several related families. Smaller, dome-shaped wigwams served as temporary shelters during hunting and gathering expeditions. Social organization was built around matrilineal clans – typically the Turtle, Wolf, and Turkey – where lineage was traced through the mother, and clan identity was crucial for marriage and social interaction. Clan leaders, often women, held significant influence, demonstrating a more egalitarian societal structure than many European cultures of the time.

Spirituality permeated every aspect of Lenape life. They believed in a Great Spirit (Kishélemukon) and a pantheon of lesser spirits associated with the natural world – the sun, moon, stars, animals, and plants. Ceremonies and rituals, often accompanied by drumming, singing, and dancing, were performed to give thanks, seek guidance, and maintain balance with the spiritual realm. The concept of land ownership, as understood by Europeans, was alien to the Lenape. Land was not a commodity to be bought and sold, but a sacred trust, a source of life to be cared for and shared by all living beings.

The arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century marked a profound and irreversible turning point for the Lenape. Henry Hudson’s exploration of the river that now bears his name in 1609 brought the Dutch, followed by the Swedes, and later the English. Initial interactions were often characterized by trade – furs for European goods like tools, blankets, and firearms. However, the Europeans brought more than just goods; they brought diseases to which the Lenape had no immunity. Smallpox, measles, and influenza decimated Lenape communities, often wiping out entire villages and weakening their societal structure long before significant armed conflict erupted.

Perhaps the most iconic, yet ultimately tragic, interaction was with William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania. Penn famously sought to establish fair dealings with the Lenape, culminating in the "Great Treaty" of Shackamaxon in 1682. While the historical details of this specific event are debated, the spirit of Penn’s initial approach was one of peaceful coexistence and negotiated land purchases, a stark contrast to the violent dispossession prevalent elsewhere. Penn’s early commitment to justice and respect for Native sovereignty was groundbreaking.

However, even with Penn’s honorable intentions, the cultural chasm regarding land ownership proved insurmountable. The Lenape understood land sales as agreements for shared use or specific resource extraction, not as permanent relinquishment of all rights. Europeans, by contrast, saw it as outright transfer of title. This fundamental misunderstanding laid the groundwork for future injustices.

The most infamous betrayal was the "Walking Purchase" of 1737. Building on an ambiguously worded and likely fraudulent deed from 1686, Penn’s sons and colonial officials claimed the right to all land a man could walk in a day and a half. Instead of sending a casual walker, they hired three of the fastest runners in the colony, who covered an astonishing 65 miles, seizing an area larger than the state of Rhode Island and effectively displacing thousands of Lenape from their ancestral lands in southeastern Pennsylvania. This act shattered trust and forced many Lenape westward, marking the beginning of a long and painful diaspora.

The subsequent decades saw the Lenape caught in the crossfire of imperial conflicts, particularly the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. Their attempts to remain neutral or align with various European powers often backfired, leading to further land loss and violence. The relentless westward expansion of European settlers, fueled by colonial governments and later the burgeoning United States, pushed the Lenape ever further from Lenapehoking. They migrated through Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, and Kansas, each stop a temporary respite before another forced removal.

Through generations of displacement, cultural suppression, and immense hardship, the Lenape demonstrated extraordinary resilience. They adapted, integrated elements of new cultures, yet fiercely held onto their identity. Oral traditions, ceremonies, and the Lenape language (Lënapei Lüxiéewiéli) became vital tools for cultural survival, passed down in secret or in remote communities.

Today, the descendants of the Original People of the Eastern Woodlands reside in various sovereign nations across North America. In the United States, there are three federally recognized Lenape tribes in Oklahoma: the Delaware Nation, the Delaware Tribe of Indians, and the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians (which includes a significant Lenape component). In Wisconsin, the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians also includes a significant Lenape population, descended from groups who migrated with the Mohicans. In Canada, several First Nations, such as the Munsee-Delaware Nation and the Delaware of Six Nations, maintain their Lenape heritage.

Despite centuries of dispossession, these modern Lenape communities are actively engaged in cultural revitalization. Language immersion programs are working to revive the endangered Lenape language. Traditional ceremonies and arts are being practiced and taught to younger generations. Tribal governments are pursuing economic development, advocating for their sovereign rights, and working to educate the broader public about their history and enduring contributions.

The Lenape’s story is a powerful reminder of the profound impact of colonization and the remarkable strength of Indigenous peoples. Their ancient wisdom, their spiritual connection to the land, and their unwavering spirit of survival offer invaluable lessons for contemporary society. As communities across Lenapehoking and beyond increasingly acknowledge the Lenape as the original stewards of the land, their legacy is not just one of historical significance but of a living, thriving culture that continues to enrich the tapestry of North America. The Lenape, the Original People, remain a testament to the enduring human spirit and the unbreakable bond between a people and their ancestral lands.