Echoes of Sovereignty: The Enduring Quest for Legal Recognition of Aboriginal Land Rights in Australia

The story of Aboriginal land rights in Australia is a profound narrative woven from dispossession, resilience, legal battles, and a slow, often painful, journey towards justice. For over two centuries, the legal system of Australia operated under the doctrine of terra nullius – "land belonging to no one" – a legal fiction that erased the ancient custodianship of Indigenous Australians and justified the colonial seizure of their ancestral lands. This historical injustice, however, has gradually been challenged and overturned, giving rise to a complex and evolving framework for the legal recognition of Aboriginal land rights.

The struggle for land recognition is not merely about property; it is about identity, culture, spirituality, and self-determination. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, land is not a commodity but a living entity, an intrinsic part of their being, their law, and their Dreaming. As the late Aboriginal elder and artist Bill Neidjie famously stated, "This is my country, my father’s country, my mother’s country, my grandfather’s country, my grandmother’s country. This is my home, where I belong." This deep spiritual and cultural connection underpins every claim for land rights and underscores the profound impact of its loss.

The Seeds of Change: Early Protests and Political Action

While the landmark legal victories of the late 20th century captured national attention, the fight for land rights has roots stretching back decades. One of the earliest and most iconic acts of defiance was the Wave Hill Walk-Off in 1966. Led by Gurindji elder Vincent Lingiari, over 200 Aboriginal stockmen and their families walked off the vast Vestey’s cattle station in the Northern Territory, protesting appalling working conditions and demanding the return of a portion of their traditional lands.

Initially a strike for better wages, the walk-off evolved into a powerful land rights protest. It took nine years of persistent campaigning, but in 1975, the then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam poured sand into Lingiari’s hands, symbolically returning the land to the Gurindji people. This gesture, captured in an enduring photograph, marked a pivotal moment, signaling a shift in national consciousness and demonstrating that Aboriginal voices could compel change. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, enacted by the Whitlam government, was the first federal legislation to allow Aboriginal people to claim rights to land based on traditional ownership.

The Legal Earthquake: Mabo v Queensland (No. 2)

Despite these early successes, the fundamental premise of terra nullius remained unchallenged in common law. That changed dramatically on June 3, 1992, with the High Court of Australia’s decision in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2). This landmark ruling, initiated by Eddie Koiki Mabo of the Meriam people of the Murray Islands in the Torres Strait, irrevocably altered the legal landscape of Australia.

The High Court, in a 6-1 majority decision, found that the Meriam people held native title to their land and, crucially, that the doctrine of terra nullius was a legal fiction that should no longer be applied. Justice Brennan, in his leading judgment, famously declared, "The fiction by which the rights and interests of indigenous inhabitants in land were treated as non-existent was justified by the colonial policy of the day. It is now time to acknowledge the past and to sweep away the notion that this continent was terra nullius at the time of European settlement."

The Mabo decision did not grant land rights; rather, it recognized that native title had always existed under Australian common law and continued to exist where it had not been extinguished by valid acts of government. It acknowledged Indigenous peoples’ prior sovereignty, even if it was overridden by Crown sovereignty upon annexation. This ruling was nothing short of a legal earthquake, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between Indigenous Australians and the state, and paving the way for a national framework for native title.

The Legislative Response: The Native Title Act 1993

In response to the Mabo decision, the federal government, under Prime Minister Paul Keating, enacted the Native Title Act 1993. This comprehensive legislation aimed to provide a legal framework for the recognition and protection of native title rights across Australia. The Act established the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) to mediate native title claims and provided processes for determining claims through negotiation and, if necessary, through the Federal Court.

Keating’s address at Redfern Park in 1992, delivered shortly after the Mabo decision, remains one of the most significant speeches in Australian political history. He spoke frankly about the historical injustices: "We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practiced discrimination and exclusion. It was our ignorance and our prejudice." He urged Australians to confront their past and work towards reconciliation, stating, "Mabo is an historic decision. But it is up to us – the non-Aboriginal people of Australia – to make the most of it." The Native Title Act, while imperfect, was a direct legislative attempt to do just that.

Navigating the Complexities: Wik and Beyond

The implementation of the Native Title Act was not without its challenges and further legal battles. One of the most significant was Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996). The Wik and Thayorre people of Cape York claimed native title over areas subject to pastoral leases. Many non-Indigenous Australians, particularly farmers and miners, feared that native title would extinguish their existing rights, leading to widespread anxiety and a political "bucketloads of extinguishment" campaign by the conservative opposition.

The High Court, in a 4-3 decision, found that native title and pastoral leases could, in fact, co-exist. Where there was a conflict of rights, the rights of the pastoralist would prevail, but native title was not automatically extinguished by the grant of a pastoral lease. This nuanced decision clarified that native title was not a full freehold title but a bundle of rights that could vary depending on the specific traditions and customs of the Indigenous group and the nature of the competing land interests. It ushered in an era of complex negotiations and Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs), which are voluntary agreements between native title holders and other parties regarding the use and management of land and waters.

Subsequent cases, such as Yorta Yorta v Victoria (2002), further defined the stringent requirements for proving native title, emphasizing the need for a continuous connection to land and adherence to traditional laws and customs. These requirements have proven difficult for many Aboriginal groups to meet, particularly those who experienced severe disruption and displacement due to colonization.

Impact and Significance

Despite the complexities and limitations, the legal recognition of Aboriginal land rights has had a profound impact:

- Overturning Terra Nullius: This is perhaps the most significant achievement, fundamentally correcting a historical injustice and recognizing the continuous presence and sovereignty of Indigenous Australians.

- Cultural Preservation: Native title provides a legal basis for Aboriginal people to access, manage, and protect their sacred sites, cultural heritage, and traditional practices on their ancestral lands. It strengthens cultural identity and facilitates the intergenerational transfer of knowledge.

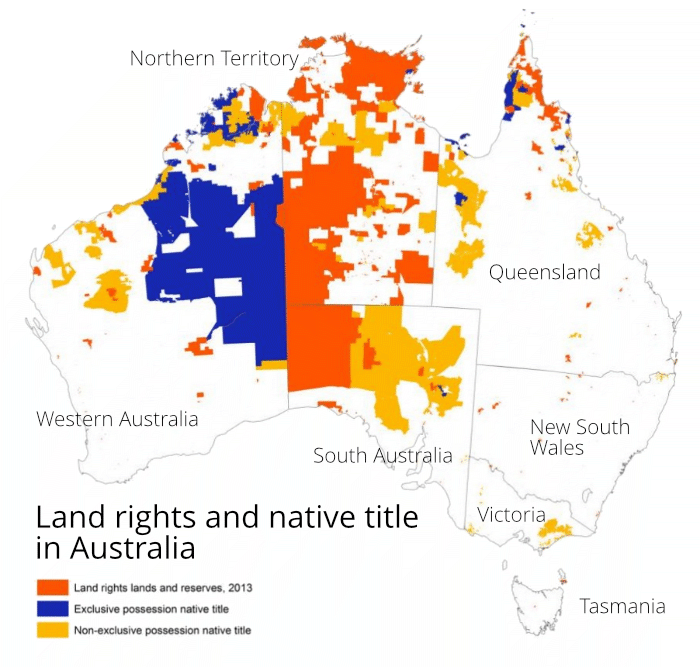

- Economic Opportunities: Native title and ILUAs have opened pathways for Indigenous communities to engage in economic development, including co-management agreements for national parks, resource agreements with mining companies, and sustainable land use projects. Over 30% of Australia’s landmass is now subject to some form of native title or Indigenous land ownership.

- Self-Determination: Land rights empower Indigenous communities to make decisions about their country, fostering greater self-determination and strengthening their capacity to address social and economic disparities.

- Reconciliation: The process of seeking and achieving native title, while often arduous, contributes to the broader national journey of reconciliation by acknowledging past wrongs and building new relationships based on respect and recognition.

Ongoing Challenges and The Path Forward

The journey is far from over. Significant challenges remain:

- Complexity and Cost: Native title claims are notoriously complex, lengthy, and expensive, often requiring extensive historical, anthropological, and legal research.

- Burden of Proof: The burden of proving continuous connection to land and traditional laws and customs, often after generations of forced removal and cultural disruption, remains a significant hurdle.

- Limited Scope: Native title, as recognized, is often a "bundle of rights" rather than full freehold ownership, and it can be extinguished by valid government acts. This can lead to frustration when communities desire more comprehensive control over their lands.

- Resource Conflicts: Tensions persist between native title interests and the demands of resource extraction, as tragically highlighted by the destruction of the 46,000-year-old Juukan Gorge rock shelters by Rio Tinto in 2020, despite the traditional owners’ objections.

- Treaty and Voice: The Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017) calls for Voice, Treaty, and Truth. While native title is a form of legal recognition, it falls short of a comprehensive treaty that would formally establish the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Australian state on a nation-to-nation basis, and enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

The legal recognition of Aboriginal land rights claims has been a monumental step, transforming the legal, social, and cultural fabric of Australia. It is a testament to the unwavering resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the slow, grinding work of legal and political advocacy. From the sands of Wave Hill to the highest courts of the land, the echoes of sovereignty have grown louder. Yet, the full realization of justice, self-determination, and a truly reconciled nation requires more than legal recognition alone. It demands continued dialogue, empathy, and a national commitment to listening to Indigenous voices and addressing the unfinished business of history. The Mabo decision opened the door, but the path to genuine equity and a shared future is still being forged, one step, one claim, and one conversation at a time.