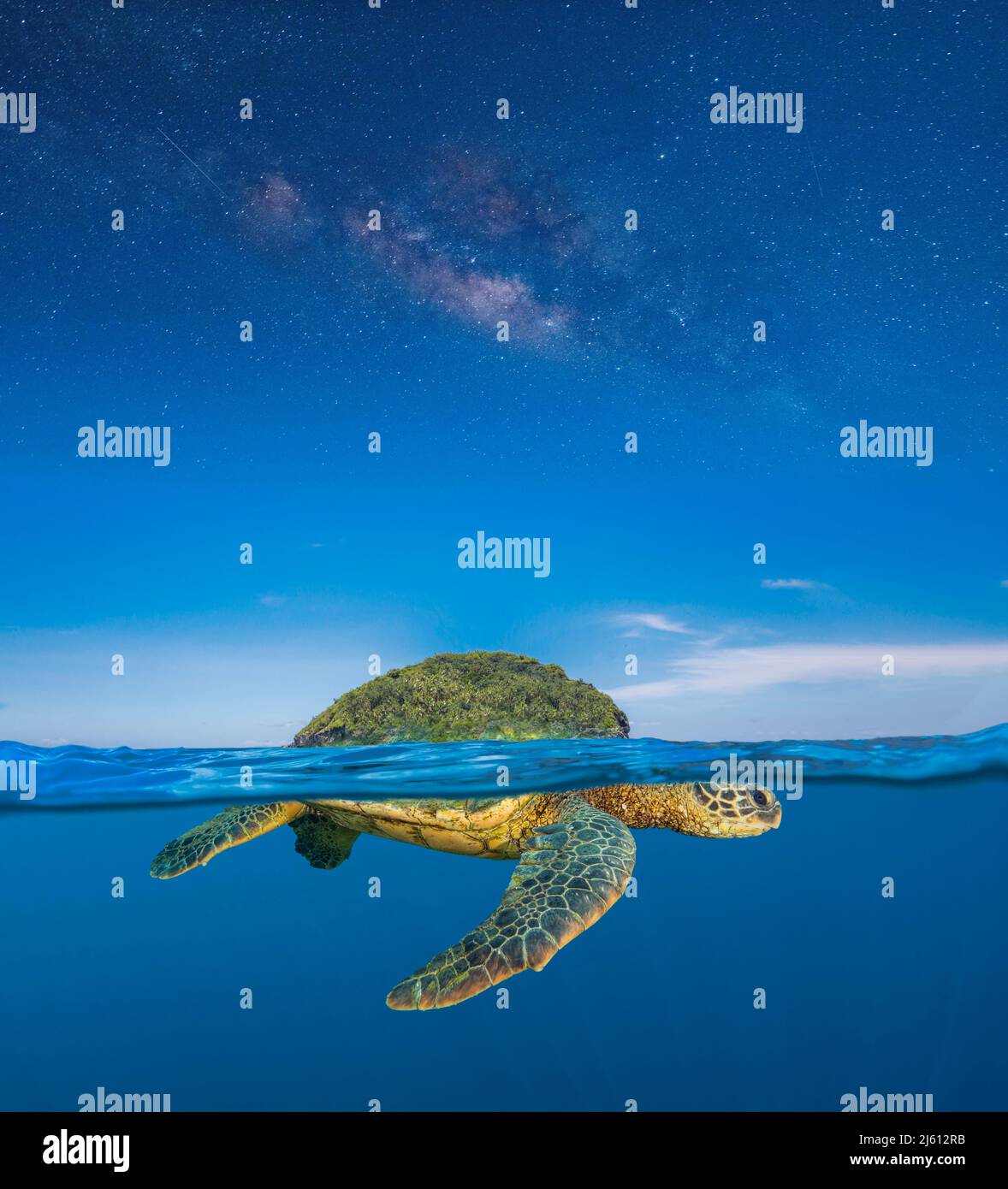

The Enduring Battle for Turtle Island: Indigenous Land Rights in the Crosshairs of Law and Legacy

Across the vast expanse of Turtle Island – the Indigenous name for North America – a profound and enduring legal struggle unfolds. It is a battle for land, sovereignty, and the very soul of Indigenous nations, fought not just in the hushed halls of courtrooms but on the front lines of ancestral territories. Despite centuries of colonial assertion and the imposition of foreign legal systems, Indigenous peoples continue to assert their inherent rights to lands and resources, challenging the foundations of modern states and demanding a future rooted in justice and self-determination.

The legal challenges facing Indigenous land on Turtle Island are multifaceted, deeply rooted in history, and perpetually reshaped by contemporary resource demands. From pipeline projects bisecting sacred sites to mining operations threatening pristine ecosystems, the conflict between Indigenous land stewardship and settler-state economic imperatives is a defining characteristic of North American jurisprudence. This article delves into the complex legal landscape, examining key precedents, ongoing disputes, and the fundamental principles at stake in this critical struggle.

The Genesis of Dispossession: A Colonial Legacy

The roots of current land disputes lie in the Doctrine of Discovery, a series of 15th-century Papal Bulls that granted European Christian explorers the right to claim lands inhabited by non-Christians. This doctrine, later enshrined in international law and adopted by North American courts, effectively erased Indigenous sovereignty and laid the groundwork for the assertion of Crown (Canada) and federal (U.S.) title over Indigenous lands. It presented a legal fiction that Indigenous peoples either did not own their land or only possessed a usufructuary right, meaning a right to use, but not to full ownership.

In both Canada and the United States, this doctrine facilitated the signing of treaties – often under duress or misrepresentation – that ceded vast territories in exchange for annuities, reserves, and promises that were frequently broken. Where no treaties were signed, as in much of British Columbia, Indigenous title was simply ignored or extinguished through legislative fiat. This historical dispossession created a legal vacuum and a moral stain that continues to fuel the contemporary land rights movement.

Canada: The Evolving Landscape of Aboriginal Title and Rights

Canada’s legal framework for Indigenous land rights has undergone significant evolution, primarily through landmark Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decisions. Prior to the 1970s, the concept of Aboriginal title was largely ignored. However, the Calder v. Attorney General of British Columbia (1973) case, though a split decision, acknowledged the pre-existence of Aboriginal title, forcing the federal government to begin negotiating land claims.

The Constitution Act, 1982, enshrined existing Aboriginal and treaty rights, providing a constitutional basis for Indigenous claims. This was followed by the seminal R. v. Delgamuukw (1997) decision, where the SCC clarified the nature of Aboriginal title. It ruled that Aboriginal title is an inherent, collective right to the land itself, stemming from pre-existing occupation, and includes the right to exclusive use and occupation for a variety of purposes, not just traditional ones. Crucially, it also established that the Crown has a "duty to consult and accommodate" Indigenous peoples whenever it considers actions that might adversely affect Aboriginal rights or title.

The Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014) case marked another historic milestone. For the first time, the SCC made a declaration of Aboriginal title over a specific tract of land, recognizing the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s exclusive rights to 1,750 square kilometers of their traditional territory. This ruling provided a concrete roadmap for how Aboriginal title could be proven and affirmed its strength, stating that once proven, title land cannot be used by the Crown without the consent of the title-holding nation, unless it can demonstrate a compelling and substantial public purpose and satisfy its fiduciary duty.

Despite these legal victories, implementation remains a formidable challenge. The "duty to consult and accommodate" is a constant source of contention. Indigenous communities frequently argue that consultation is superficial, a mere box-ticking exercise rather than a meaningful dialogue leading to genuine accommodation or consent. Corporations, backed by provincial and federal governments, often proceed with projects, claiming adequate consultation, while Indigenous nations assert their right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), a standard articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

A prominent contemporary example is the Coastal GasLink pipeline project cutting through Wet’suwet’en traditional territory in British Columbia. While elected band councils along the pipeline route have signed agreements with CGL, the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, who assert jurisdiction over their unceded territory according to their traditional governance system, have consistently opposed the project. This conflict highlights the complex interplay between traditional Indigenous governance structures and the Indian Act-imposed elected band council system, often exploited by proponents to create division and claim legitimacy. The repeated RCMP enforcement of injunctions against Wet’suwet’en land defenders underscores the continued use of state force to facilitate resource extraction on contested Indigenous lands.

United States: Tribal Sovereignty and the Trust Responsibility

In the United States, Indigenous nations are recognized as "domestic dependent nations" with inherent sovereignty, though subject to the plenary power of Congress. This unique legal status means that tribes possess powers of self-government over their members and territory, including the ability to form governments, make laws, and establish courts. However, this sovereignty is limited by federal law, and the U.S. government has a "trust responsibility" to protect tribal lands, resources, and self-governance.

The historical trajectory in the U.S. has been marked by policies of forced removal (e.g., the Trail of Tears), reservation establishment, and attempts at assimilation (e.g., the Dawes Act, which privatized communal tribal lands). Today, the legal battles often revolve around the federal government’s fulfillment of its trust responsibility, the protection of treaty rights, and the assertion of tribal jurisdiction over reservation and ancestral lands.

A crucial battleground has been the protection of sacred sites and cultural resources. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) conflict at Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016-2017 brought global attention to the intersection of environmental justice, treaty rights, and sacred site protection. The pipeline, slated to cross under the Missouri River, threatened the tribe’s sole source of drinking water and traversed ancestral burial grounds and sacred sites, violating treaty rights and raising serious environmental concerns. The tribe argued that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had failed in its duty to consult and adequately assess the environmental and cultural impacts. While the immediate protests were met with state violence, legal challenges have continued, with courts repeatedly finding the environmental review process flawed, though the pipeline remains operational.

Another significant case involves the designation and reduction of national monuments. In 2017, President Trump significantly reduced the size of Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, a landscape sacred to numerous Indigenous nations. These nations argued that the reduction ignored their deep cultural connections to the land, which holds countless archaeological sites and traditional use areas. The Antiquities Act, under which the monument was initially designated, allows presidents to protect culturally and scientifically significant lands. The legal challenge, arguing against the President’s authority to reduce a monument, underscored the ongoing struggle for Indigenous voices to be central in federal land management decisions affecting their ancestral territories. President Biden later restored the monument’s original boundaries, a significant victory for the coalition of tribes.

Common Threads and Persistent Obstacles

Across Turtle Island, several common threads weave through these legal challenges:

- Resource Extraction: The demand for oil, gas, minerals, timber, and hydroelectric power is the primary driver of conflict, placing Indigenous lands, often rich in natural resources, directly in the path of industrial development.

- Jurisdictional Complexity: Overlapping and often conflicting jurisdictions between federal, provincial/state, and Indigenous governments create legal ambiguities that are exploited by project proponents.

- Economic Disparity: Many Indigenous communities face socio-economic challenges, leading to pressures to accept resource development projects that promise jobs and revenue, even when they come at a significant cultural or environmental cost.

- Environmental Justice: Indigenous communities disproportionately bear the brunt of environmental degradation from industrial projects, impacting their health, traditional food sources, and cultural practices.

- Lack of Political Will: Despite legal precedents, governments often exhibit a reluctance to fully uphold their constitutional obligations or implement international standards like FPIC, leading to protracted legal battles and on-the-ground confrontations.

A Glimmer of Hope: International Standards and "Land Back"

Amidst the ongoing struggles, there are significant advancements and renewed calls for justice. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted by Canada and endorsed by the U.S., though not legally binding in domestic law, serves as a powerful moral and political framework. It affirms Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination, to their traditional lands, territories, and resources, and the right to FPIC for any project affecting their lands. Its principles are increasingly cited in domestic legal arguments and policy discussions.

The "Land Back" movement, gaining momentum across Turtle Island, represents a more assertive and holistic approach to Indigenous sovereignty. It is not just about legal title but about restoring Indigenous governance, revitalizing traditional economies, and healing the land. This movement pushes beyond the confines of settler-state legal systems to envision a future where Indigenous nations exercise full jurisdiction over their homelands.

Recent court victories, such as Tsilhqot’in, demonstrate that Indigenous peoples can achieve significant legal recognition of their inherent rights. Moreover, growing public awareness and support, fueled by environmental movements and a broader reckoning with colonial history, are adding pressure on governments and corporations to respect Indigenous land rights.

Conclusion

The legal challenges for Indigenous land on Turtle Island are a microcosm of the ongoing struggle for justice and reconciliation. They expose the profound tension between historical dispossession and the enduring assertion of Indigenous sovereignty. While legal frameworks have evolved, the systemic barriers rooted in colonial legacy and the relentless pursuit of resource extraction continue to demand vigilance and resistance from Indigenous nations.

The path forward requires more than just legal recognition; it necessitates a fundamental shift in power dynamics, genuine adherence to the principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, and a commitment to implementing the spirit, not just the letter, of treaty and Aboriginal rights. Until Indigenous peoples are empowered to be the primary decision-makers on their ancestral lands, the battle for Turtle Island will continue, a testament to the resilience of Indigenous nations and a profound challenge to the conscience of the settler states.