Giants of the Ocean: The Leatherback Sea Turtle’s Fight for Survival, Echoed from Turtle Island

With a lineage stretching back over 100 million years, the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) is not merely the largest living reptile; it is a profound testament to ancient marine life, a true titan of the deep. Yet, this magnificent creature, distinct in its leathery, rather than bony, shell, faces an existential crisis, its future hanging precariously in the balance. From the critical nesting beaches of places like Turtle Island, a beacon of conservation in Southeast Asia, the urgent call to protect these majestic wanderers resonates across the globe.

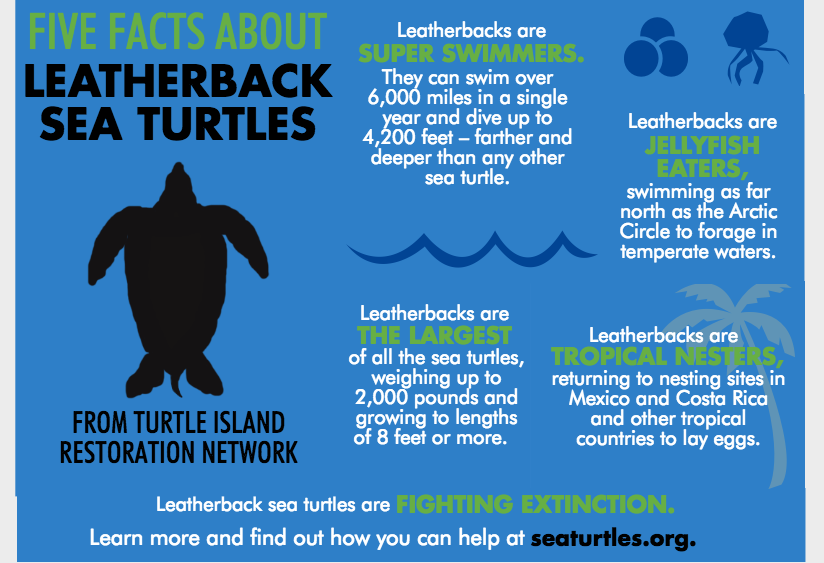

The leatherback is a creature of superlatives. Reaching lengths of up to seven feet (2.2 meters) and weighing over 2,000 pounds (900 kg), its sheer size dwarfs all other sea turtle species. Its most striking feature, and the origin of its name, is its unique carapace. Unlike the hard, bony shells of other turtles, the leatherback’s shell is a mosaic of thousands of small bones embedded in a thick, leathery skin. This flexible, streamlined design, accented by seven prominent ridges running from head to tail, is perfectly adapted for navigating vast ocean currents and undertaking epic migrations.

A Deep Diver and Master Migrator

The leatherback’s anatomical marvels extend beyond its shell. Equipped with massive front flippers that can span over nine feet (2.7 meters), it is an unparalleled swimmer, capable of traversing entire ocean basins. These turtles undertake the longest migrations of any reptile, traveling thousands of miles between their cold-water foraging grounds and tropical nesting beaches. For instance, populations nesting in the Caribbean may forage off the coasts of Canada, a journey of over 6,000 miles (9,600 km) one way.

Their unique physiology also allows them to dive deeper than any other sea turtle, reaching depths of over 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) – deeper than any other air-breathing vertebrate except for some whales and seals. This incredible ability is attributed to their flexible shell, collapsible lungs, and the ability to slow their heart rate, all of which help them withstand immense pressure. These deep dives are often in pursuit of their primary prey: jellyfish.

The Jellyfish Specialist: An Ancient Diet with Modern Perils

Leatherbacks are obligate jellyfish eaters, consuming hundreds of pounds of these gelatinous creatures daily. Their esophagus is lined with backward-pointing spines, perfectly designed to trap and process their slippery diet. This specialized diet places them at a critical juncture in the marine food web, helping to control jellyfish populations. However, this ancient dietary preference has become a modern Achilles’ heel.

"The leatherback’s reliance on jellyfish makes it incredibly vulnerable to plastic pollution," explains Dr. Lena Karlsson, a marine biologist working on turtle conservation in the region. "To a foraging leatherback, a floating plastic bag looks indistinguishable from a jellyfish. Ingesting plastic can block their digestive tracts, leading to starvation and death. It’s a tragic irony that something so ancient is so susceptible to a purely modern threat."

Life’s Perilous Journey: From Nest to Ocean

The life cycle of a leatherback begins on remote, sandy beaches, primarily in tropical regions. Females, after their arduous migrations, return to the same general area where they were born, often under the cloak of darkness. They dig deep nests, typically laying clutches of 60 to 90 fertilized eggs, along with a number of smaller, yolkless ‘spacer’ eggs. A single female can lay multiple clutches in a nesting season, returning to the sea for a period before re-emerging to nest again.

The incubation period lasts approximately 60 to 70 days, influenced by sand temperature, which also determines the sex of the hatchlings – warmer sands produce more females, cooler sands more males. Once hatched, the tiny leatherbacks, no bigger than a human palm, embark on a perilous race to the sea, dodging predators like crabs, birds, and even wild pigs. Their journey is fraught with danger, and only a tiny fraction of hatchlings will survive to adulthood, estimated to be as low as 1 in 1,000.

Turtle Island: A Symbol of Hope Amidst the Struggle

While Turtle Island (Pulau Penyu) in Sabah, Malaysia, is predominantly known for its green and hawksbill turtle nesting, it stands as a powerful symbol of the broader efforts required to safeguard all sea turtle species, including the more elusive leatherback, whose nesting sites are often more remote and scattered. The principles applied at Turtle Island – meticulous data collection, egg incubation, and controlled release – are scalable models for leatherback conservation worldwide.

At Turtle Island, rangers patrol beaches nightly, carefully collecting newly laid eggs and relocating them to protected hatcheries to shield them from poachers, predators, and tidal inundation. This hands-on approach significantly increases the survival rate of hatchlings during their most vulnerable stage. Visitors to the island can witness these conservation efforts firsthand, fostering a crucial connection between humans and these ancient mariners.

"Places like Turtle Island are living classrooms," says Alex Tan, a park ranger with years of experience. "They show us what’s possible when we commit to protecting these creatures. Even though leatherbacks are rarer visitors here, the lessons we learn, the methods we refine, directly inform efforts to protect them on their primary nesting beaches in places like Trinidad, Costa Rica, or Papua New Guinea."

The Looming Threats: A Multifaceted Crisis

Despite dedicated conservation efforts, leatherback populations face a gauntlet of threats, pushing them towards the brink of extinction. The Pacific leatherback populations, particularly in the Eastern Pacific, have suffered catastrophic declines, plummeting by over 90% in recent decades, earning them a "Critically Endangered" status from the IUCN. Atlantic populations, while showing some signs of stabilization in certain areas, remain vulnerable.

Beyond plastic pollution, other significant threats include:

-

Fisheries Bycatch: This is arguably the most pervasive threat. Leatherbacks frequently become entangled in fishing gear such as gillnets, longlines, and trawls, leading to injury or drowning. Efforts to mitigate this include the use of Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) in trawl nets, which allow turtles to escape, and the implementation of seasonal fishing closures in critical habitats.

-

Habitat Loss and Degradation: Coastal development, artificial lighting, and erosion degrade crucial nesting beaches. Light pollution disorients hatchlings, drawing them away from the ocean and towards inland dangers.

-

Climate Change: Rising sea levels threaten to inundate nesting beaches, while increasing sand temperatures skew hatchling sex ratios towards females, potentially leading to a lack of males necessary for reproduction. Changes in ocean currents and prey distribution also impact their foraging success.

-

Egg Poaching: While less prevalent in some regions due to increased patrols, illegal harvesting of eggs for consumption or sale continues to be a threat in others.

A Glimmer of Hope and the Path Forward

Despite the grim outlook for some populations, there are glimmers of hope. Robust conservation efforts in the Caribbean, particularly in Trinidad and Tobago, have led to stabilizing or even increasing leatherback nesting numbers. These successes underscore the importance of international cooperation, strong legislative frameworks, and community engagement.

The path forward demands a multi-pronged approach:

- Continued Research: Understanding migration patterns, foraging habits, and population dynamics is crucial for effective conservation.

- Stronger Policy and Enforcement: Implementing and enforcing regulations to reduce bycatch, control coastal development, and combat illegal egg harvesting.

- Waste Management and Pollution Control: Addressing the global plastic crisis is paramount for jellyfish-eating species like the leatherback.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions to stabilize global temperatures and protect critical habitats.

- Public Awareness and Education: Fostering a global appreciation for these magnificent creatures and inspiring collective action.

The leatherback sea turtle, with its ancient lineage and incredible adaptations, is a living fossil, a sentinel of the deep. Its continued survival is not just a testament to our commitment to biodiversity; it is a measure of our own responsibility to the planet’s most magnificent, yet vulnerable, inhabitants. From the symbolic shores of Turtle Island to the vast, open ocean, the call to protect these giants must be heard and acted upon, ensuring their epic journey continues for millennia to come.