The Resurgence of Voice: Reclaiming Indigenous Languages on Turtle Island

Across Turtle Island, a quiet but powerful revolution is unfolding – a determined, deeply rooted effort to reclaim and revitalize Indigenous languages. These languages, once the vibrant arteries of diverse cultures, carrying millennia of knowledge, law, and worldview, faced systemic suppression for centuries. Now, from bustling urban centers to remote reserves, a new generation, supported by elders and guided by a profound sense of cultural imperative, is fighting to bring these voices back from the brink of silence. This is not merely an academic exercise; it is a profound act of decolonization, a healing of historical wounds, and an urgent assertion of identity and sovereignty.

The historical context for this struggle is stark. When European colonizers arrived on Turtle Island, they encountered hundreds of distinct Indigenous languages, each a unique vessel for understanding the world, interacting with the land, and maintaining social cohesion. In what is now Canada, there were over 60 distinct languages; in the United States, hundreds more. Yet, the policies of assimilation, most notably through residential and boarding schools, aimed explicitly to "kill the Indian in the child," often beginning with the eradication of native languages. Children were punished, sometimes brutally, for speaking their mother tongues. This systematic linguistic genocide severed generations from their cultural roots, creating a devastating intergenerational trauma that continues to impact communities today. The result is a critical endangerment of many Indigenous languages, with only a handful retaining a significant number of fluent speakers.

"Our language isn’t just words; it’s our connection to the land, to our ancestors, to who we are as a people," explains Elder Clara Buffalo, a Cree language keeper from Maskwacis, Alberta. "When you lose your language, you lose a piece of your soul, your way of thinking. Our ceremonies, our traditional laws, they all make sense in Cree, not in English." This sentiment is echoed across Turtle Island, underscoring the understanding that Indigenous languages are not simply alternative forms of communication; they are entire epistemological systems. They encode unique perspectives on kinship, governance, environmental stewardship, and spirituality that are often untranslatable into colonial languages. To lose a language is to lose an entire world.

The urgency of revitalization efforts is palpable. Many fluent speakers, the last direct link to unbroken linguistic traditions, are elders, and their numbers are dwindling. This creates a critical window of opportunity, a race against time to capture and transmit this invaluable knowledge before it is lost forever. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which Canada and the United States have endorsed, explicitly affirms the right of Indigenous peoples to revitalize, use, develop, and transmit their languages to future generations. This international recognition provides a crucial framework for advocacy and support, though the implementation varies greatly.

The methods employed in this revitalization movement are as diverse as the languages themselves, often blending traditional teaching methods with modern technology. Immersion schools are proving to be one of the most effective strategies. Institutions like the Akwesasne Freedom School in northern New York, which has been teaching Mohawk exclusively since 1979, exemplify this approach. Children learn everything from math to history in their ancestral language, fostering an environment where fluency becomes natural and deeply ingrained. Graduates of such schools are now becoming the next generation of teachers, creating a self-sustaining cycle of language transmission.

Another powerful model is the Master-Apprentice program, pioneered by linguist Leanne Hinton in California. This intensive, one-on-one approach pairs a fluent elder with a dedicated learner for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of hours of direct interaction, often conducting daily activities entirely in the target language. This method is particularly effective for highly endangered languages with very few remaining speakers, allowing for the rapid transfer of conversational fluency and cultural nuances.

Technology is also playing an increasingly vital role. Online dictionaries, language learning apps, and social media groups are connecting learners with resources and with each other. Duolingo, for instance, offers courses in Navajo and Hawaiian, reaching millions globally. Podcasts, YouTube channels, and even video games are being developed in Indigenous languages, making learning accessible and engaging for younger generations who are digital natives. These platforms not only aid in learning but also help normalize and celebrate the use of Indigenous languages in contemporary contexts.

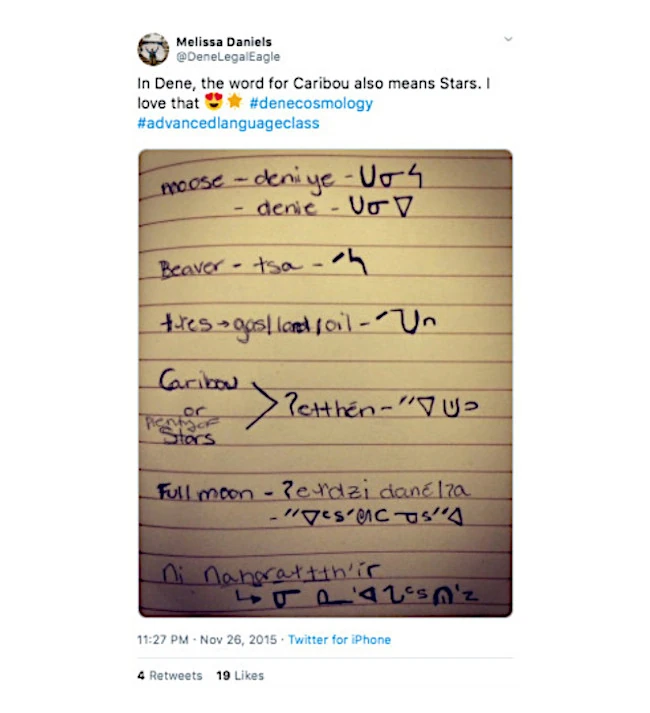

Beyond formal education, community-led initiatives are the backbone of language revitalization. Land-based learning, which connects language to traditional territories and practices, is particularly potent. Learning the names of plants, animals, and geographical features in one’s language while on the land deepens both linguistic and cultural understanding. Youth language camps, intergenerational storytelling circles, and community feasts conducted in Indigenous languages are creating vibrant spaces where language is not just studied but lived.

However, the path to revitalization is fraught with challenges. The most immediate is the advanced age of many fluent speakers. "Every elder we lose is like a library burning down," laments Dr. Mary Jane Norris, an Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) language activist. "We are in a race against time, and we need resources, people, and political will to catch up." Funding remains a persistent hurdle, with many initiatives relying on grants and volunteer efforts rather than consistent institutional support. The sheer scale of language loss means that many communities are starting with very few, if any, fluent speakers, requiring monumental efforts to reconstruct dormant languages using historical texts and recordings.

Moreover, the lingering effects of intergenerational trauma can make language learning emotionally challenging. For some, the language carries memories of pain and oppression, while others grapple with feelings of shame or inadequacy for not knowing their ancestral tongue. Creating safe, supportive learning environments that acknowledge and address these historical burdens is crucial for success.

Despite these formidable obstacles, the impact of language revitalization is profoundly positive. Communities that are actively reclaiming their languages report stronger cultural identities, increased self-esteem among youth, and a deeper connection to traditional knowledge and ceremonies. For many, speaking their language is a powerful act of healing and resistance, a reclaiming of agency and a reassertion of Indigenous nationhood.

"When I speak Mohawk, I feel strong, connected," says Kanonhsí:io, a young learner at a language immersion program. "It’s not just about words; it’s about understanding my ancestors, my history, and my place in the world. It’s empowering." This sense of empowerment is critical for Indigenous youth, who often navigate the complexities of identity in a world dominated by colonial languages and cultures.

The journey to revitalize Indigenous languages on Turtle Island is a long and arduous one, demanding sustained commitment, creativity, and unwavering belief in the inherent value of these unique linguistic treasures. It requires not just financial investment but also a fundamental shift in societal attitudes, recognizing these languages not as relics of the past but as living, evolving systems vital for the future. As communities continue to lead these efforts, supported by allies and enlightened policies, the collective voice of Turtle Island’s original languages is slowly, powerfully, rising again, ensuring that future generations will not only know who they are but can articulate it in the sacred tongues of their ancestors. This is more than survival; it is a vibrant, hopeful resurgence.