Guardians of the Plains: The Sacred Traditions and Enduring Cultural Heritage of the Lakota Sioux

The vast, sweeping expanse of the Great Plains, where the sky meets the earth in an endless horizon, has for millennia been home to the Lakota Sioux. More than just a geographic location, this land, known as Paha Sapa (the Black Hills) in their sacred tongue, is the very crucible of their identity, a spiritual heartland pulsating with traditions forged over countless generations. The Lakota, a vibrant and resilient people, are one of the three main divisions of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), commonly referred to as the Sioux, a French corruption of an Ojibwe word meaning "little snake." Their own name, Lakota, translates simply to "friends" or "allies," a testament to their deep-seated values of community and kinship.

To understand the Lakota is to journey into a world where every element of existence – the wind, the buffalo, the stones, the stars – is imbued with spirit and interconnectedness. At the core of Lakota spirituality lies the concept of Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery or Great Spirit, an all-encompassing force that permeates the universe. This is not a distant, anthropomorphic deity, but rather an omnipresent power, a sacred web of relations binding all life. This profound understanding is encapsulated in their most revered phrase: "Mitakuye Oyasin" – All My Relations. It is a prayer, a philosophy, and a way of life, acknowledging that all beings, human and non-human, are part of a single, sacred family.

For centuries, the Lakota lived a semi-nomadic life, their existence intricately woven with the movements of the buffalo (Tatanka), which they regarded as a sacred gift from Wakan Tanka. The buffalo was not merely a source of food; it provided shelter (tipis made from hides), clothing, tools, weapons, and even spiritual sustenance. Its very existence dictated their migrations, their ceremonies, and their social structure. This symbiotic relationship fostered a deep respect for nature and a profound sense of gratitude, ensuring that nothing was wasted. Every hunt was preceded by prayer and followed by thanksgiving, a ritual acknowledgment of the life given for the community’s survival.

The spiritual life of the Lakota is expressed through a rich tapestry of sacred ceremonies, each designed to foster communion with Wakan Tanka, purify the spirit, and strengthen the community. These rites, passed down through oral tradition by wise elders and holy men (Wichasha Wakan), form the bedrock of their cultural heritage:

-

The Inipi (Sweat Lodge Ceremony): This ancient purification ritual takes place in a dome-shaped lodge, often covered with blankets, representing the womb of Mother Earth. Heated stones, known as "Grandfathers," are placed in a central pit, and water is poured over them to create steam. Participants pray, sing, and reflect in the darkness, seeking spiritual cleansing, healing, and guidance. It is a powerful experience of rebirth and renewal, connecting participants to the elements and to the Great Spirit.

-

The Hanblecheyapi (Vision Quest): A solitary journey of profound spiritual significance, the Vision Quest is undertaken by individuals seeking guidance, purpose, or a deeper connection to Wakan Tanka. After purification in the sweat lodge, a seeker ventures alone to a remote, sacred place, fasting and praying for several days, often without food or water. The purpose is to humble oneself, to listen to the whispers of the spirits, and to receive a vision or message that will guide one’s life path. As the revered Oglala Lakota holy man Black Elk stated, "The first peace, which is the most important, is that which comes within the souls of men when they realize their relationship, their oneness, with the universe and all its powers, and when they realize that at the center of the universe dwells Wakan-Tanka, and that this center is really everywhere, it is within each of us."

-

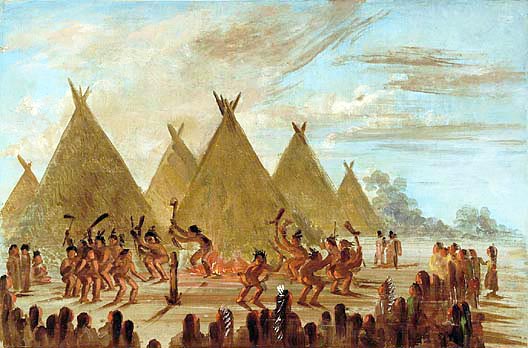

The Wiwanyang Wacipi (Sun Dance): Perhaps the most profound and sacred of all Lakota ceremonies, the Sun Dance is a grueling four-day ritual of prayer, sacrifice, and renewal for the entire community. Participants, often men, offer their flesh as a sacrifice, dancing around a central cottonwood tree (the Tree of Life) and enduring pain to pray for their people, for healing, and for the well-being of all creation. This ceremony, once outlawed by the U.S. government, has been powerfully revitalized and remains a central pillar of Lakota spiritual life, demonstrating immense courage, faith, and communal devotion.

-

The Chanunpa (Sacred Pipe Ceremony): The sacred pipe is a powerful conduit for prayer and connection to Wakan Tanka. Its bowl, typically made of red catlinite stone, represents the earth, and the stem, usually wood, represents all that grows upon it. When smoked, the smoke carries prayers to the heavens, uniting the earth and sky. The pipe is used in virtually all Lakota ceremonies and gatherings, symbolizing truth, peace, and unity among all beings.

Beyond these formal ceremonies, the Lakota cultural heritage is rich with oral traditions. Storytelling is not merely entertainment but a vital pedagogical tool, transmitting history, moral lessons, spiritual teachings, and cultural values from one generation to the next. Elders, as keepers of this knowledge, play a crucial role in shaping the youth, ensuring the continuity of their language (Lakȟóta), customs, and identity. The Lakota language itself is a living repository of their worldview, with nuances and concepts that cannot be fully translated into English, emphasizing the importance of its preservation.

The late 19th century brought an unprecedented upheaval to the Lakota way of life. The relentless westward expansion of European settlers, driven by the concept of "Manifest Destiny," led to devastating conflicts, broken treaties, and the systematic destruction of the buffalo herds – a deliberate strategy to subdue the Plains tribes. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 had ostensibly guaranteed the Lakota a vast reservation, including the sacred Black Hills, "as long as the grass shall grow and the waters run." However, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills just six years later triggered a massive influx of miners, violating the treaty and sparking the Great Sioux War.

This period saw the rise of legendary Lakota leaders such as Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and chief, and Crazy Horse, an Oglala Lakota war leader, who valiantly fought to protect their people and their land. The Battle of Greasy Grass (known as the Battle of Little Bighorn) in 1876, where Lakota and Cheyenne warriors annihilated Custer’s 7th Cavalry, stands as a testament to their military prowess and fierce determination. However, the tide of history, backed by overwhelming military force, proved insurmountable.

The Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were slaughtered by U.S. troops, marked a tragic end to the Indian Wars and symbolized the profound suffering inflicted upon Indigenous peoples. Following this, the Lakota were confined to reservations, their children forcibly removed to boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian to save the man," where their language and culture were suppressed. This era of forced assimilation left deep scars, disrupting family structures, eroding traditional knowledge, and leading to intergenerational trauma that continues to impact Lakota communities today.

Despite these immense challenges and historical injustices, the Lakota spirit has proven indomitable. In the 20th and 21st centuries, there has been a powerful resurgence of cultural pride and revitalization efforts. Lakota communities are actively working to reclaim their language through immersion schools, teach traditional crafts and ceremonies, and restore their spiritual practices. The ongoing struggle for the return of the Black Hills, deemed "never ceded" by the Lakota, remains a potent symbol of their fight for sovereignty and justice. Although the U.S. Supreme Court awarded monetary compensation for the land in 1980, the Lakota have consistently refused it, insisting that the land itself, not money, is what they seek.

Today, the Lakota people face contemporary challenges common to many Indigenous communities – poverty, health disparities, and struggles for economic development on reservations. Yet, their resilience, their deep connection to their sacred traditions, and their unwavering commitment to "Mitakuye Oyasin" continue to inspire. Their story is not just one of past glory and tragic loss, but one of ongoing strength, adaptation, and a profound spiritual wisdom that holds valuable lessons for the modern world. The Lakota remind us of the importance of living in harmony with nature, of the power of community, and of the enduring strength of a people deeply rooted in their sacred heritage. Their voices, like the winds across the Great Plains, continue to echo with the wisdom of the ancestors, guiding the path forward for generations to come.