Echoes from the Greasy Grass: Lakota Resistance and Vision at Little Bighorn

The sun beat down on the Montana plains on June 25, 1876, illuminating a scene of both idyllic peace and simmering tension. Along the banks of the Little Bighorn River, or "Greasy Grass" as the Lakota knew it, lay one of the largest encampments of Plains Indians ever assembled: thousands of tipis, stretching for miles, housing Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho families. Children played, women prepared meals, and warriors, emboldened by prophecy and a fierce determination to preserve their way of life, sharpened their resolve. This day, however, would shatter that peace and etch itself into the annals of history, not as a simple battle, but as a profound testament to resistance, vision, and the enduring spirit of a people fighting for their very existence.

The story of Little Bighorn is often told through the lens of General George Armstrong Custer’s "Last Stand," a narrative that frames the Lakota and Cheyenne as a nameless, faceless enemy. But from the Lakota perspective, it was the "Battle of the Greasy Grass," a decisive victory born from spiritual power, strategic brilliance, and an unwavering commitment to their land and traditions, spearheaded by visionary leaders like Sitting Bull and the indomitable Crazy Horse.

The roots of this monumental clash lay deep in a century of broken promises and relentless westward expansion. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had ostensibly guaranteed the Lakota exclusive use of the Great Sioux Reservation, including the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa), "as long as the grass shall grow and the water flow." Yet, just six years later, Custer himself led an expedition into the Black Hills, confirming the presence of gold. The subsequent gold rush triggered a tide of white prospectors and settlers, violating the treaty and sparking renewed conflict. The U.S. government, rather than enforcing its own treaty, moved to acquire the Black Hills, ordering all Lakota and Cheyenne to report to agencies by January 31, 1876, or be deemed "hostile." For those who lived off the land, far from agency control, this was an impossible and unacceptable demand.

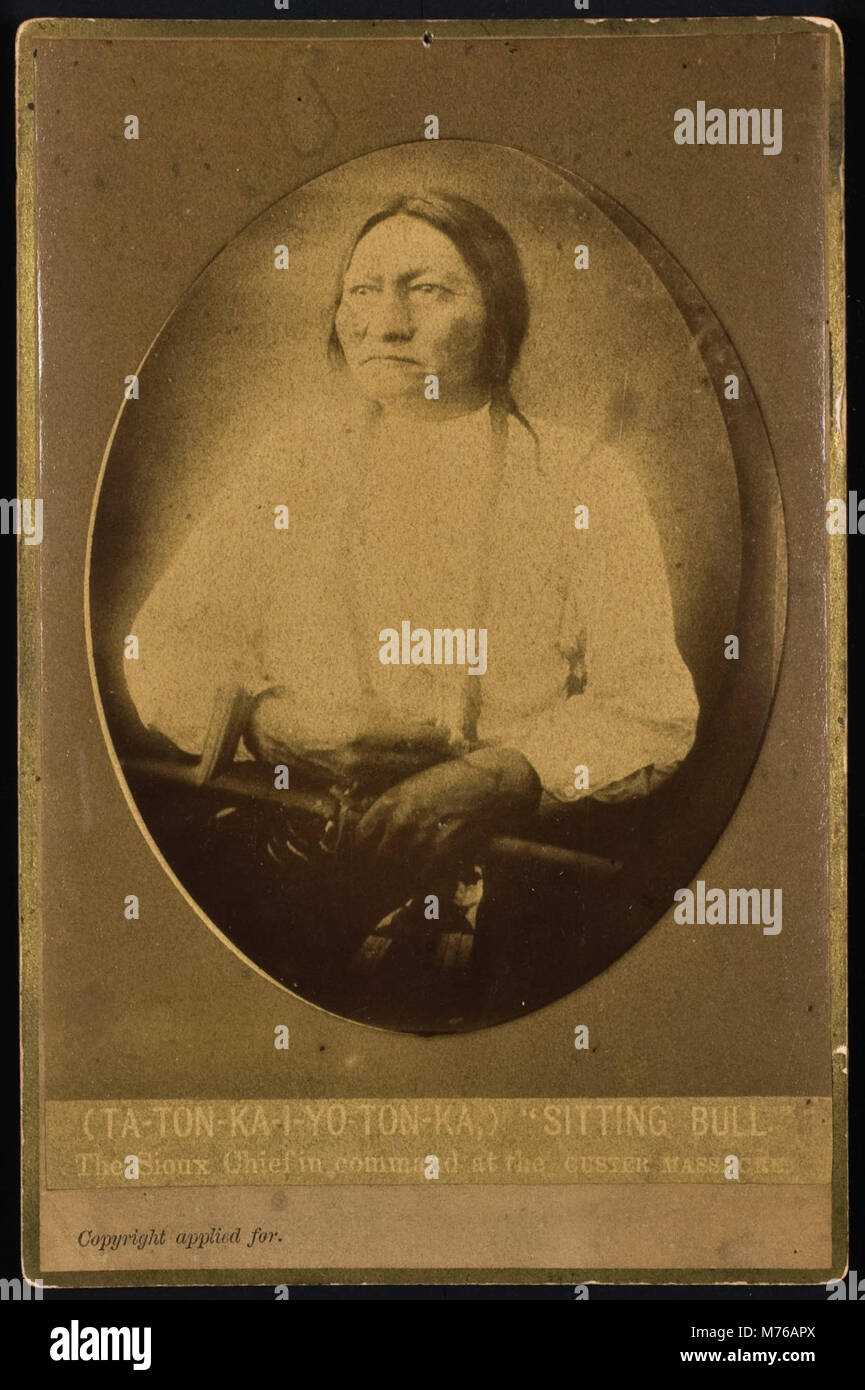

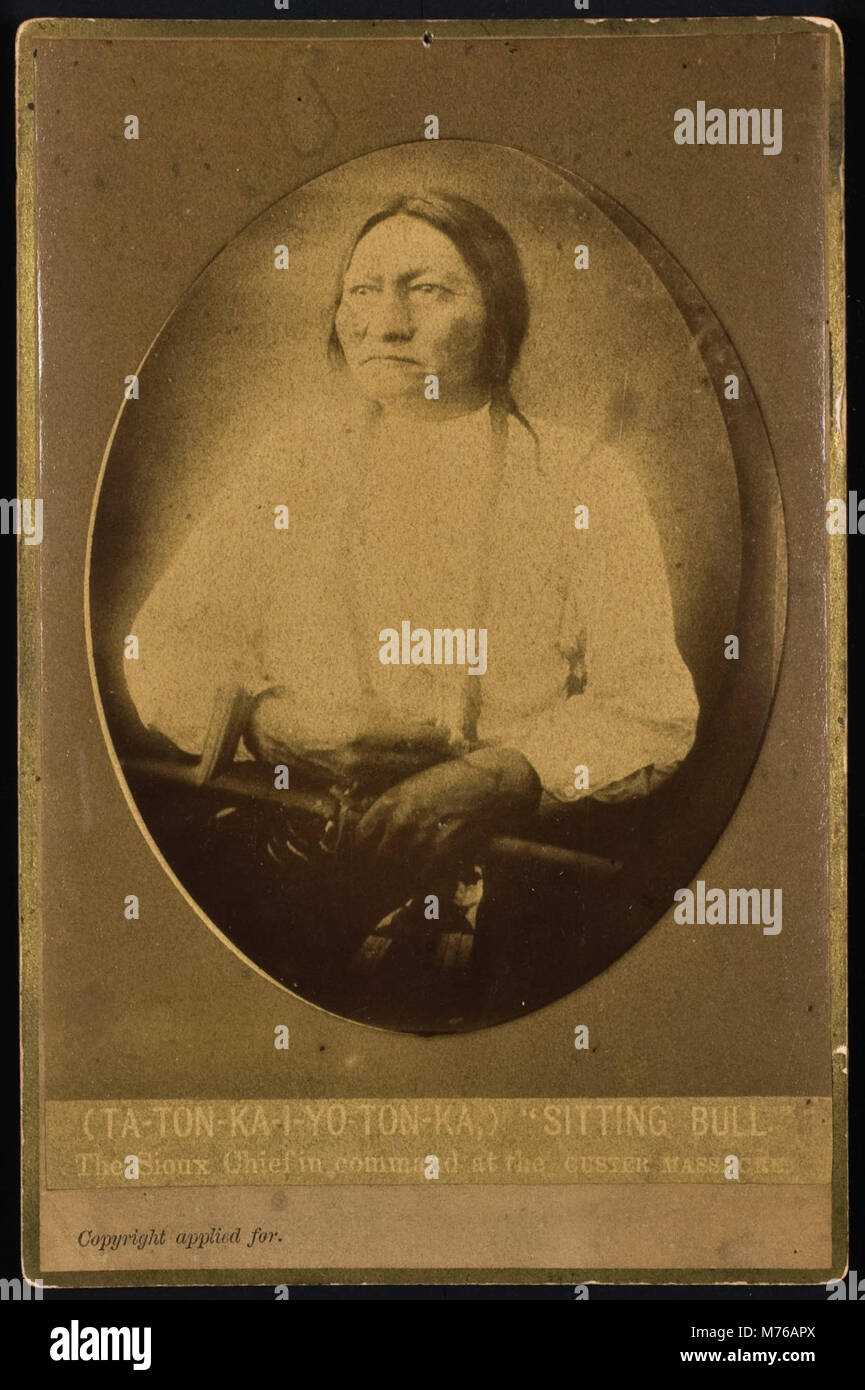

This was the backdrop against which Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and chief, rose to prominence as a spiritual and political leader. He was not a war chief in the traditional sense, but his wisdom, courage, and profound connection to the spiritual world commanded immense respect. In early June 1876, at a Sun Dance on the Rosebud Creek, Sitting Bull performed the excruciating ritual, offering 100 pieces of flesh from his arms as a sacrifice. During his trance, he received a powerful vision: "I saw soldiers coming into camp, but they had no ears. They were falling into camp upside down." This vision was interpreted as a prophecy of a great victory over the white soldiers, a sign that the Great Spirit favored their resistance. It galvanized the Lakota and Cheyenne, instilling a profound sense of spiritual confidence and unity.

Thousands converged on the Greasy Grass, drawn by Sitting Bull’s vision and the growing frustration with the encroaching whites. This was not a pre-planned war party but a gathering of families seeking safety, buffalo, and a final assertion of their sovereign way of life. The encampment was massive, perhaps 7,000 to 10,000 people, with an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 warriors, making it one of the largest concentrations of Native American power in the Plains during that era.

The U.S. Army, under the command of General Alfred Terry, launched a three-pronged campaign to force the "hostiles" onto reservations. Custer, leading the 7th Cavalry, was tasked with locating the main village. Driven by ambition and a desire for glory, Custer pressed ahead, ignoring warnings about the size of the Native American force. On June 25, his scouts spotted the immense encampment. In a fateful decision, Custer divided his command, sending Major Marcus Reno to attack the southern end of the village while he circled north, intending to trap the inhabitants.

Reno’s attack, however, quickly faltered. As his cavalry charged, they were met by a furious counter-attack led by chiefs like Gall, a Hunkpapa war leader known for his tactical prowess. The warriors, who had initially been surprised, quickly rallied, protecting their families. "We were eating our dinner when the attack came," Gall later recounted. "I snatched up my gun and mounted my horse, calling to my young men to follow me." Reno’s troops were driven back into a defensive position in the timber along the river, then up onto a bluff, suffering heavy casualties.

It was during this initial phase that Crazy Horse, the legendary Oglala Lakota war chief, emerged as a pivotal figure. Known for his quiet demeanor, exceptional courage, and uncanny ability to appear out of nowhere, Crazy Horse embodied the spirit of resistance. He was a master of cavalry tactics, using the terrain to his advantage and inspiring his warriors with his fearlessness. "He would simply say, ‘Come on, we can do it,’ and he would be the first to lead the charge," described his cousin, Black Elk.

As Reno’s men were pinned down, Custer, approaching from the north, was met by an even more overwhelming force. The warriors, alerted to Custer’s approach, streamed north from the village, many of them fresh from repelling Reno. Crazy Horse, seeing Custer’s divided command and audacious push, seized the moment. He led a massive charge that enveloped Custer’s five companies, outflanking them and pushing them back onto a series of ridges, culminating in what would become known as "Last Stand Hill."

From the Lakota perspective, Custer’s "last stand" was not a heroic final defense but a desperate, chaotic rout. The warriors, fueled by Sitting Bull’s prophecy and the need to protect their families, fought with ferocious intensity. They were superior in numbers, intimately familiar with the terrain, and driven by a righteous anger. Accounts from Lakota and Cheyenne participants describe soldiers panicking, firing wildly, and being systematically overwhelmed. "The soldiers were entirely surrounded," said White Bull, a nephew of Sitting Bull, who claimed to have fought Custer hand-to-hand. "We wiped them out." Within little more than an hour, all 210 men under Custer’s immediate command were dead, including Custer himself.

The victory, however, was a Pyrrhic one. While the Lakota and Cheyenne had successfully defended their camp and inflicted a stunning defeat on the U.S. Army, the ultimate outcome was devastating. The U.S. government responded with intensified military campaigns, relentless pursuit, and a hardening of policy. The "Great Sioux War" escalated. Sitting Bull and his followers fled to Canada, seeking refuge, but eventually returned due to starvation, surrendering in 1881. Crazy Horse, after continued resistance, surrendered in 1877, only to be killed under suspicious circumstances while imprisoned at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. His famous declaration, often attributed to him, "Hokahey! It’s a good day to die!" encapsulates the warrior spirit he embodied, though the precise wording and context of its utterance remain debated.

The Battle of Little Bighorn, or the Greasy Grass Fight, remains a powerful symbol. For the Lakota and Cheyenne, it represents a moment of triumph, a time when their spiritual strength, unity, and military prowess allowed them to defend their sovereignty against overwhelming odds. It was a moment when Sitting Bull’s vision was realized, and Crazy Horse’s bravery shone brightest. It stands as a testament to their fierce independence and their profound connection to the land and their traditions.

Today, the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument stands as a somber reminder of this clash of cultures. It tells the story not just of Custer’s defeat, but also of the Lakota and Cheyenne victory, acknowledging the courage and sacrifice of all who fought. The echoes from the Greasy Grass continue to resonate, reminding us of the cost of expansion, the importance of treaties, and the enduring spirit of indigenous peoples who, against all odds, fought to preserve their way of life, guided by the visions of their leaders and the strength of their ancestors. It is a story not of a "last stand," but of a profound and sacred resistance.