Okay, here is a journalistic article about the history of the Klamath Tribes of Oregon, approximately 1200 words in length, in English.

Echoes of Resilience: The Enduring History of the Klamath Tribes of Oregon

The vast, ancient lands of the Upper Klamath Basin in southern Oregon whisper tales of profound connection, devastating loss, and unyielding resilience. For millennia, this ruggedly beautiful landscape has been the ancestral home of the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Band of Snake Paiute people, collectively known today as the Klamath Tribes. Their history is a powerful narrative, a microcosm of the Indigenous experience in America – a story etched in treaties and betrayals, in the rise and fall of a self-sufficient empire, and in an ongoing fight to reclaim sovereignty, culture, and their sacred water.

Ancient Roots: People of the Water and Wocus

Long before the arrival of European settlers, the Kla-Mo-Ya people thrived in a rich and diverse ecosystem centered around the vast expanse of Upper Klamath Lake. Their traditional territory spanned millions of acres, from the volcanic Cascade peaks to the high desert plateaus, a landscape that provided an abundance of resources and shaped their spiritual worldview.

The Klamath people, known as Maqlaqs or "the people," were intimately connected to the land and its cycles. Their lifeways revolved around the seasonal harvesting of wocus (the seeds of the yellow water lily), a staple food that was gathered, dried, and ground into flour, sustaining them through long winters. Fishing, especially for salmon and trout that once teemed in the Klamath River system, was central to their existence, as was hunting deer, elk, and waterfowl. The Modoc, closely related and often intermarried, occupied lands south of Klamath Lake, sharing similar traditions but also developing distinct identities shaped by their specific territories. The Yahooskin, a Paiute band, ranged further east, skilled in desert survival and interweaving with the Klamath and Modoc through trade and kinship.

Their creation stories speak of Llao, the spirit of the underworld dwelling in Mount Mazama (Crater Lake), and Skell, the spirit of the sky. These tales, passed down through generations, reinforce their deep spiritual connection to the land and their understanding of its powerful forces. "Our history is written in the landscape itself," one elder once reflected. "Every mountain, every river, every marsh holds a memory of our ancestors, their struggles, and their triumphs." This profound sense of place would be severely tested by the relentless tide of westward expansion.

The Treaty Era: Promises and Cessions

The mid-19th century brought an irreversible shift. Trappers, explorers, and eventually gold seekers and homesteaders began to encroach upon Klamath lands, disrupting traditional lifeways and bringing disease. The U.S. government, driven by a policy of "manifest destiny" and a desire for land, sought to formalize its control.

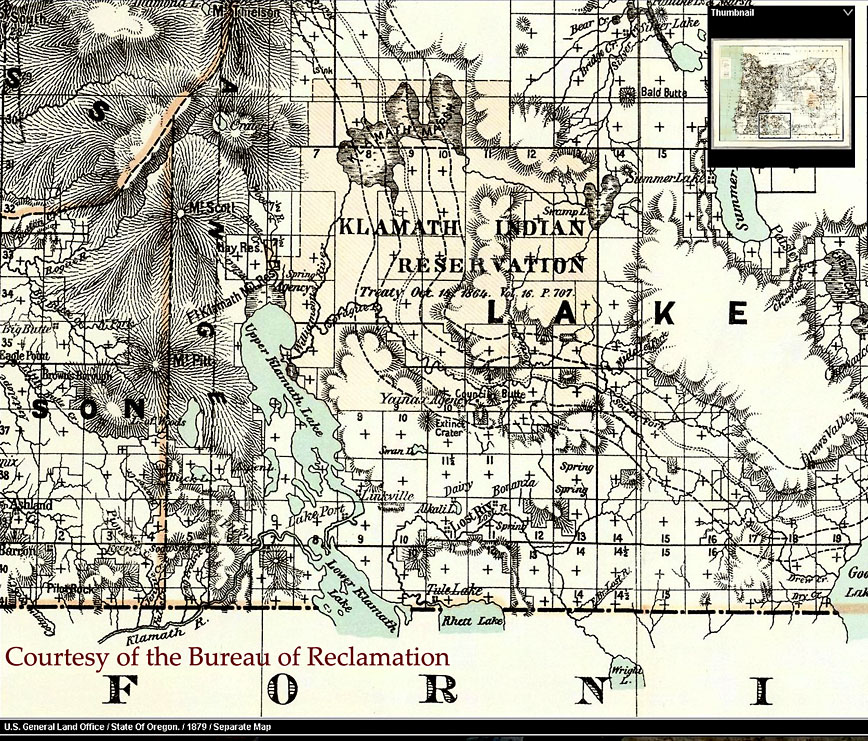

On October 14, 1864, the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Paiute leaders gathered at Council Grove and signed a pivotal treaty with the United States. In exchange for ceding millions of acres of their ancestral domain – a territory larger than the state of Connecticut – the tribes retained a reservation of approximately 1.9 million acres, encompassing their core traditional lands around Upper Klamath Lake. The treaty promised perpetual federal protection, essential services, and the exclusive right to hunt, fish, and gather on their remaining lands.

While the treaty secured a homeland, it was not without immense cost and underlying tensions. The Modoc, particularly, felt their traditional homelands were not adequately protected by the reservation boundaries, contributing to grievances that would later erupt into the tragic Modoc War of 1872-73, a desperate fight for their homeland that ended with the defeat and execution of Modoc leader Captain Jack and the forced removal of his people to Oklahoma. For those who remained on the Klamath Reservation, the treaty era marked a period of adaptation, as the tribes navigated the complex and often contradictory policies of the Indian Office while striving to maintain their cultural identity.

The Timber Empire: A Model of Self-Sufficiency

Despite the challenges, the Klamath Reservation became a remarkable success story in the early 20th century. Blessed with vast, old-growth ponderosa pine forests, the Klamath people developed a sophisticated and highly profitable timber industry. Under tribal management and with federal oversight, they established sustainable forestry practices long before the term became mainstream. They built sawmills, managed their forests carefully, and invested their profits wisely.

By the 1940s and 50s, the Klamath Tribes were one of the wealthiest tribes per capita in the United States. Their timber resources were so extensive and so well-managed that they generated substantial income for tribal members and funded essential services on the reservation, including schools, health clinics, and social programs. The Klamath Indian Forest was renowned as a model of economic self-sufficiency and resource management.

"We were thriving," remembers a descendant whose grandparents worked in the mills. "We had our own economy, our own way of life, our own dignity. We showed what was possible when a tribe could manage its own resources." This prosperity, however, inadvertently made them a target for a new, devastating federal policy.

The Termination Era: A Catastrophic Betrayal

In the mid-20th century, the U.S. government embarked on a policy known as "Termination." Driven by a misguided belief that Indigenous peoples should be assimilated into mainstream American society and no longer required federal oversight, Congress began to terminate the federal recognition of tribes, ending their trust relationship with the government and liquidating their assets. The Klamath Tribes, due to their perceived wealth and the "readiness" of their members for assimilation, became a prime target.

The Klamath Termination Act of 1954 was a catastrophic blow. Despite significant opposition from many tribal members, the act dissolved the tribe’s federal recognition, dismantled their tribal government, and forced the sale of their vast, communal timberlands and other assets. Tribal members were given a choice: "withdraw" from the tribe and receive a per capita payment from the sale of assets, or remain in a diminished tribal entity that would soon lose all its land and services.

The consequences were devastating. The carefully managed forests were sold off, often at undervalued prices, to private timber companies, leading to widespread clear-cutting and environmental damage. The per capita payments, while seemingly substantial at the time, were quickly depleted by many who lacked experience managing large sums, or who were preyed upon by unscrupulous individuals.

"It felt like we were orphaned overnight," shared a tribal elder, recalling the period. "Our land, our government, our culture – everything was stripped away. We lost our identity, our purpose, our way of life. It brought so much pain, so much poverty, so much brokenness." The termination era plunged the Klamath people into decades of economic hardship, social disarray, and profound cultural trauma, leaving a deep scar that persists to this day.

The Fight for Restoration: Reclaiming Identity

Despite the immense losses, the spirit of the Klamath people could not be extinguished. Over the decades that followed termination, a new generation of leaders emerged, determined to reverse the injustice. They organized, lobbied, and educated, refusing to let their history be erased. Their perseverance, coupled with a broader national movement for Indigenous rights, eventually led to a turning point.

On August 15, 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed the Klamath Restoration Act, officially re-establishing federal recognition for the Klamath Tribes. It was a momentous victory, a testament to decades of tireless advocacy. However, unlike other restored tribes, the Klamath were restored without their land base. The vast reservation, the timber empire, was gone. The challenge now was to rebuild a sovereign nation from scratch, without the foundational land and economic resources that had once sustained them.

"Restoration wasn’t a magic wand," a former tribal council member explained. "It was the beginning of another long journey. We had to recreate our government, our institutions, our services, all while working to acquire land and rebuild our economic future, piece by painful piece."

Contemporary Challenges: Water, Land, and Cultural Revitalization

Today, the Klamath Tribes continue their journey of rebuilding and revitalization. They have re-established their tribal government, developed essential services, and are actively working to acquire ancestral lands, though on a much smaller scale than their original domain. Cultural programs are vital, focusing on language preservation, traditional arts, and ceremonies, ensuring that the ancient wisdom is passed to future generations.

One of the most significant and ongoing challenges facing the Klamath Tribes is the complex issue of water rights in the Klamath Basin. The basin is a nexus of competing demands: the needs of endangered salmon and other native fish, the irrigation demands of agriculture, and the senior water rights of the Klamath Tribes, which stem from their 1864 treaty. Decades of drought, climate change, and habitat degradation have exacerbated these conflicts, leading to frequent crises where water is shut off to farmers, or flows are restricted, devastating fish populations.

The Klamath Tribes hold the most senior water rights in the basin, rights crucial for the health of their traditional fisheries and the cultural continuity of their people. "Water is life for us," states a current tribal leader. "It’s not just about irrigation or fish counts; it’s about our spiritual connection, our treaty rights, and the very survival of our culture. We are fighting for the health of the entire ecosystem, for everyone who depends on this water."

The struggle for the Klamath River’s health is paramount. After decades of advocacy, the planned removal of four dams on the Lower Klamath River, set to begin in 2024, represents a monumental victory for the tribes and a beacon of hope for salmon restoration and ecosystem recovery. It is a testament to their unwavering commitment to healing the river that defines them.

The history of the Klamath Tribes is a story of extraordinary resilience. From the ancient rhythms of the wocus harvest to the devastating silence after termination, and now to the powerful resurgence of their voice, the Klamath people stand as living proof of the enduring strength of Indigenous cultures. Their journey is far from over, but their determination to reclaim their heritage, protect their lands and waters, and secure a vibrant future for their children echoes powerfully through the Oregon landscape, a testament to a people who refuse to be forgotten.