Echoes on Paper: Kiowa Ledger Art as a Chronicle of Warrior Spirit and Cultural Resilience

The vast, undulating plains of North America once thrummed with the hooves of buffalo and the shouts of warriors. For the Kiowa people, a formidable Southern Plains tribe, life was defined by the horse, the hunt, and the intricate dance of intertribal relations, often involving conflict and displays of individual bravery. When this world irrevocably shifted under the relentless pressure of westward expansion, reservation confinement, and the deliberate decimation of the buffalo, the Kiowa, like many Native nations, faced an existential crisis. Yet, from this crucible of loss and adaptation emerged a unique and poignant art form: Kiowa Ledger Art, a vibrant testament to warrior narratives and the profound cultural transitions etched onto the unlikely canvas of accounting paper.

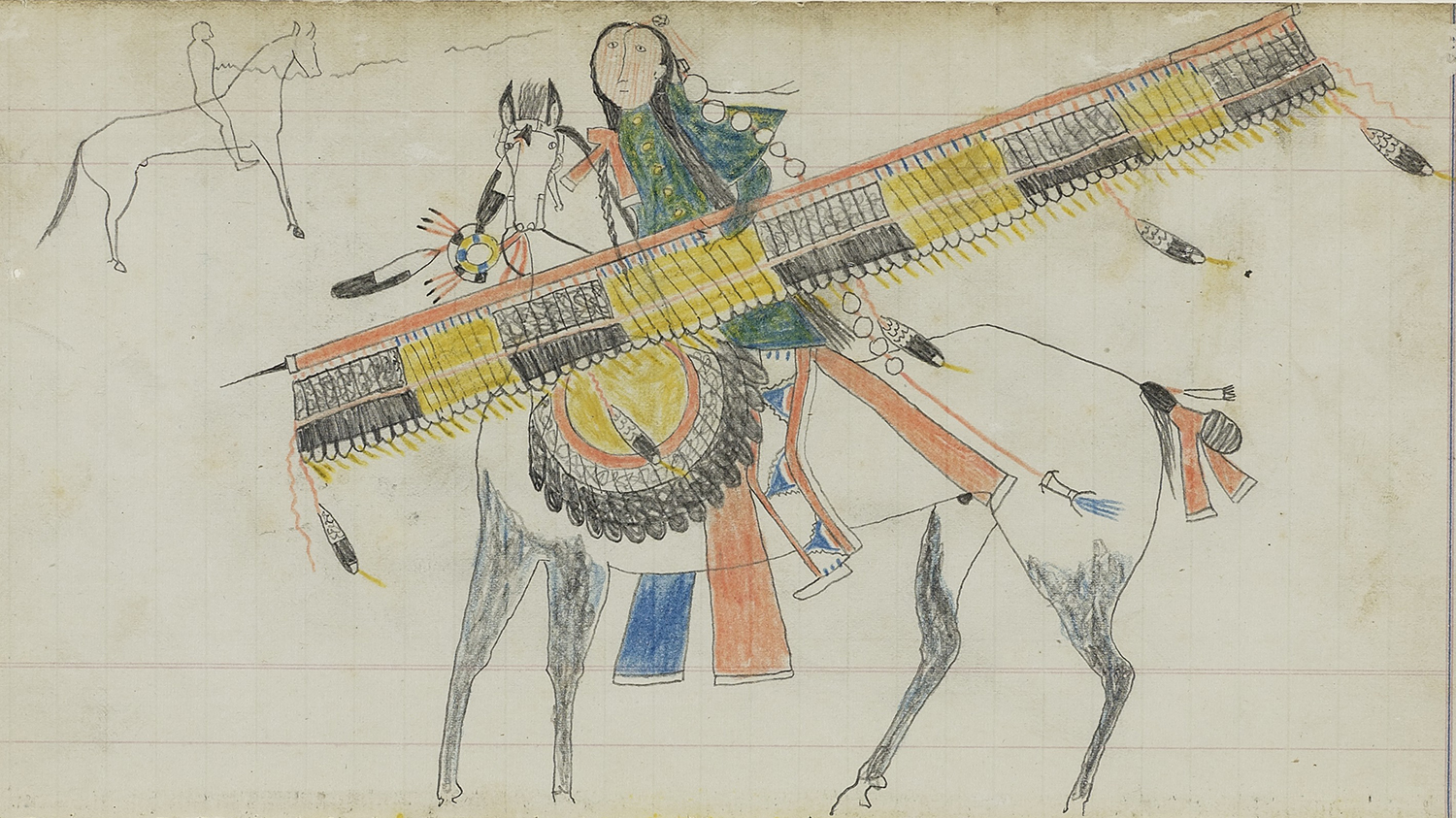

Kiowa Ledger Art is not merely decorative; it is a meticulously preserved historical record, a visual autobiography, and a powerful act of cultural assertion. These drawings, typically executed with pencil, crayon, and ink on discarded ledger books, ration coupons, or other available paper, document a pivotal period from the late 19th to early 20th centuries. They bridge the chasm between a remembered past of nomadic freedom and a stark present of enforced settlement, offering an unparalleled window into the Kiowa worldview during an era of profound upheaval.

The genesis of ledger art is inextricably linked to the dramatic shift in Native American life following the Plains Wars. After the Red River War of 1874-75, many Southern Plains warriors, including Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, were imprisoned at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. Among these prisoners were influential Kiowa figures such as Wohaw, Zotom, and Koba. Under the controversial supervision of Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt, who advocated for assimilation with the infamous slogan "Kill the Indian, save the man," these men were encouraged to draw. Pratt’s intention was to "civilize" them, but inadvertently, he provided the materials and the impetus for an artistic explosion. Deprived of traditional hide painting surfaces and materials, the prisoners readily adapted to paper and pencils, transforming mundane ledger books into vivid chronicles of their former lives.

Before the advent of ledger art, Kiowa warriors meticulously documented their deeds on buffalo or deer hide, adorning tipis, shields, and robes with pictographic representations of their exploits. These traditional forms, known as biographic or mnemonic art, served as public affirmations of an individual’s courage, generosity, and skill, essential for maintaining status within the highly stratified warrior societies. Counting coup—touching an enemy in battle without killing them—was paramount, along with horse raiding and successful hunts. When the buffalo were systematically exterminated and nomadic life was forcibly suppressed, the physical means and social context for traditional hide painting vanished. Ledger art became the direct descendant of this ancient practice, transplanting its spirit onto a new, more accessible medium.

The warrior narrative forms the core of early Kiowa ledger art. These drawings are replete with scenes of daring raids, pitched battles, and the heroic deeds of individual combatants. Figures are typically rendered in profile, with dynamic postures that convey movement and intensity. Horses, depicted with striking accuracy and often adorned with elaborate regalia, are central to these scenes, reflecting their immense value and spiritual significance to the Plains people. Artists meticulously detailed clothing, weaponry—bows, lances, rifles, and shields—and the specific hairstyles or markings of different tribes, making these drawings invaluable ethnographic records.

One common motif is the "coup count," where a warrior, often on horseback, confronts an enemy, demonstrating bravery by touching them with a coup stick or hand. The number of coups counted was a direct measure of a warrior’s prestige. Horse-stealing expeditions, another high-stakes endeavor, are also frequently depicted, celebrating the skill and daring required to acquire valuable mounts from enemy camps. These narratives were not just historical accounts; they were reaffirmations of identity, stories told to maintain the memory of a glorious past, to educate younger generations, and to assert individual and collective pride in the face of profound disempowerment.

However, Kiowa Ledger Art transcends mere battle scenes; it is a powerful chronicle of cultural transition. While early works primarily focus on the remembered past, later pieces begin to reflect the realities of reservation life and the jarring blend of old and new. Artists depicted traditional dances, ceremonies, social gatherings, and everyday activities, preserving the visual memory of a way of life that was rapidly fading. Scenes of buffalo hunts, though increasingly a memory rather than a present reality, continued to be drawn, imbued with a deep sense of nostalgia and reverence for the lost keystone of their existence.

Artists like Wohaw, a Kiowa-Comanche prisoner at Fort Marion, exemplify this transitional period. His self-portrait, "Wohaw Between Two Worlds," famously depicts him standing between a buffalo and a longhorn steer, symbolizing the profound choice and cultural dilemma faced by his people. His drawings also show interactions with non-Native people, scenes of daily life at Fort Marion, and the adoption of new clothing or tools, all rendered with the same directness and narrative power as his battle scenes. These works are poignant visual metaphors for the struggle to maintain identity while navigating an imposed new reality.

The stylistic characteristics of Kiowa ledger art are distinctive. Figures are typically two-dimensional, lacking Western perspective, a direct continuation of traditional Plains pictographic conventions. Strong outlines define forms, which are then filled with bold, often vibrant colors, limited only by the available crayons or pencils. The composition is narrative-driven, focusing on action and conveying information clearly. While initially simple, some artists developed a remarkable degree of detail and sophistication, capturing minute aspects of regalia, horse trappings, and human expression. The linear format of the ledger paper itself sometimes influenced compositions, leading to sequential narratives across pages or figures aligned along the existing lines.

The enduring significance of Kiowa Ledger Art cannot be overstated. For historians and ethnographers, these drawings are invaluable primary sources, offering unique insights into Kiowa history, social structures, material culture, and spiritual beliefs from an indigenous perspective. They often complement or even correct written historical accounts, providing an unfiltered visual record of experiences and memories.

For the Kiowa people, ledger art remains a vital link to their heritage. It is a tangible manifestation of resilience, a testament to the power of art to preserve memory and assert identity in the face of immense pressure. The tradition did not die out with the first generation of Fort Marion artists; it continued on the reservations, evolved, and has even seen a resurgence in contemporary Native American art, with artists drawing on the legacy of their predecessors to explore modern themes and identity.

In conclusion, Kiowa Ledger Art is far more than a collection of drawings; it is a profound cultural archive. It is the warrior’s spirit, refusing to be silenced, finding a new voice on paper. It is the chronicle of a people navigating an unprecedented cultural transition, remembering their past with dignity, documenting their present with keen observation, and subtly asserting their enduring presence. These vibrant pages, once mere accounting records, have been transformed into powerful historical documents, preserving the visual narratives of the Kiowa people and ensuring that their warrior spirit and cultural resilience continue to echo through time.

![]()