Divided Loyalties, Devastated Lands: The Iroquois Confederacy in the Crucible of the American Revolution

Often viewed through the lens of colonial grievances and British imperial overreach, the American Revolution was far more than a conflict between distant monarch and rebellious subjects. For the Indigenous nations of North America, particularly the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, or Haudenosaunee, the struggle for American independence was a seismic event that shattered generations of political unity, ravaged ancestral lands, and fundamentally reshaped their future. Far from passive observers, the Six Nations—Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora—were central players whose complex loyalties and strategic decisions had profound consequences, not only for themselves but for the nascent United States.

Before the Revolution, the Iroquois Confederacy stood as a formidable power, a sophisticated political and military alliance that had for centuries dominated a vast territory stretching across what is now New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and parts of Canada. Bound by the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa), their system of governance, with its emphasis on consensus and diplomacy, had impressed European observers like Benjamin Franklin, who famously noted, "It would be a strange thing if six nations of ignorant savages should be capable of forming a scheme for such a union… and yet a like union should be impracticable for ten or a dozen English colonies." Their strategic location, acting as a buffer between French Canada and the British colonies, had allowed them to play European rivals against each other, maintaining a delicate balance of power that served their interests.

However, the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War) had irrevocably altered this landscape. With the French defeated, British power surged, and the Iroquois lost their crucial leverage. The Proclamation Line of 1763, ostensibly meant to protect Indigenous lands, was increasingly disregarded by land-hungry American colonists, fueling deep distrust and resentment among the Haudenosaunee. As tensions mounted between Britain and its colonies, the Iroquois found themselves caught in an impossible bind.

Initially, the Confederacy sought to maintain neutrality, a time-honored strategy to preserve their strength and avoid internal strife. At a grand council in German Flats in August 1775, they declared their intention to remain "at peace with all parties." This stance was not merely a passive avoidance of conflict; it was an active diplomatic effort to protect their people and lands from the inevitable devastation of war. They understood that siding with one power would make them enemies of the other, inviting retaliation.

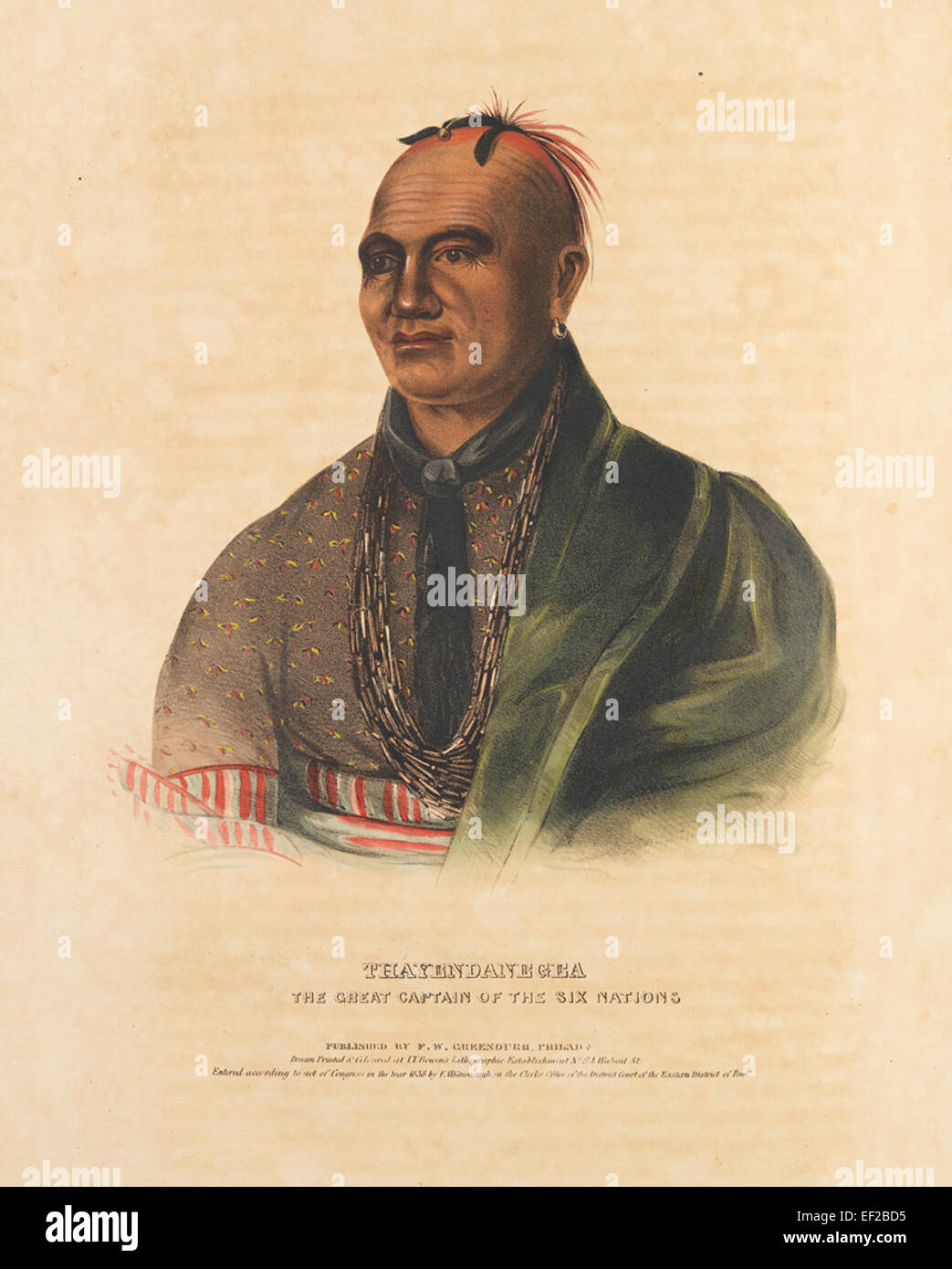

Yet, neutrality proved an increasingly untenable position. Both the British and the Americans desperately sought Iroquois alliances, recognizing the strategic importance of their warriors and their intimate knowledge of the frontier. British agents, particularly Guy Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and his charismatic protégé, the Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), tirelessly lobbied the Six Nations. Brant, educated in an English school and fluent in both Mohawk and English, was a powerful advocate for the British cause. He argued that the Crown, through treaties like the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768), had shown a greater commitment to respecting Iroquois land claims than the expansionist American colonists. He feared that an American victory would lead to unchecked westward expansion and the complete dispossession of Indigenous peoples.

On the American side, figures like the Presbyterian missionary Samuel Kirkland cultivated strong ties with the Oneida and Tuscarora, two of the Six Nations. Kirkland, who had lived among the Oneida for years, appealed to their religious sentiments and their historical grievances against British encroachment. He painted the American cause as a fight for liberty and promised that an independent United States would respect their sovereignty and land. The Oneida, in particular, had long-standing disagreements with the Mohawk over land and influence, and saw an alliance with the Americans as an opportunity to assert their own interests.

The Confederacy’s unity, once its greatest strength, began to fray. By 1777, the internal divisions reached a breaking point. The Grand Council at Onondaga, the traditional capital of the Confederacy, failed to achieve consensus. Joseph Brant led the majority of the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga to ally with the British. They believed the Crown offered the best hope for preserving their lands and way of life. Conversely, the Oneida and most of the Tuscarora sided with the American Patriots, convinced that their future lay with the emerging republic. The Onondaga, initially split, eventually saw their capital destroyed by American forces in 1779, forcing many to join the British-allied nations.

This fracturing of the Haudenosaunee was a tragedy of immense proportions, forcing kin to fight kin in a war that was not originally their own. The frontier quickly became a brutal battleground. Iroquois warriors, fighting alongside British regulars and Loyalist rangers, launched devastating raids on American settlements in the Mohawk Valley, Cherry Valley, and Wyoming Valley, seeking to disrupt the American war effort and protect their territories from encroachment. The Battle of Oriskany in August 1777, fought during the Saratoga campaign, stands as a grim testament to this internal conflict, with Oneida warriors fighting alongside American militias against their Mohawk and Seneca brethren. It was, as one historian described, "a battle where Indian fought Indian," marking a profound and painful rupture within the Confederacy.

The American response was swift and brutal. In 1779, General George Washington ordered the Sullivan-Clinton Expedition, a massive military campaign aimed at destroying the Iroquois nations allied with the British. Washington’s directive to General John Sullivan was unambiguous: "The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible… that the country may not be merely overrun but destroyed."

Over the summer of 1779, Sullivan’s forces systematically marched through Iroquois territory, burning some 40 villages and laying waste to vast tracts of agricultural land. Orchards were cut down, cornfields were scorched, and homes were reduced to ashes. The expedition’s aim was not merely to defeat the warriors but to break the spirit and capacity of the Iroquois people to wage war by destroying their means of subsistence. As one American soldier noted in his journal, "We have not left a house, nor a fruit tree, nor a grain of corn, nor a garden vegetable… from the Genesee to the Mohawk River."

The Sullivan Expedition achieved its military objectives, but at a terrible human cost. Thousands of Iroquois, now homeless and without food, became refugees, many fleeing to British-held Fort Niagara, where they endured a harsh winter marked by starvation and disease. The campaign crippled the Confederacy, scattering its people and shattering its economic base. While the British-allied Iroquois continued to fight, their ability to sustain large-scale operations was severely curtailed.

When the Treaty of Paris officially ended the American Revolution in 1783, the Iroquois Confederacy found itself in a precarious and unenviable position. The British, in their haste to secure peace with the Americans, made no provisions for their Indigenous allies, effectively abandoning them. The newly independent United States, viewing the Iroquois as a conquered enemy, moved quickly to seize their lands. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784, negotiated under duress, forced the Six Nations to cede vast tracts of their ancestral territory to New York and Pennsylvania, despite the protests of leaders like Joseph Brant, who felt betrayed by both the British and the Americans.

The war had profoundly altered the Iroquois world. The Haudenosaunee, once a unified political and military force, were now fractured, displaced, and dispossessed. Many British-allied Iroquois, led by Joseph Brant, eventually migrated to what is now Ontario, Canada, where the British granted them land along the Grand River, establishing the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve. Those who remained in New York, primarily the Oneida, Tuscarora, and some Onondaga and Seneca, faced continuous pressure from American expansion and were relegated to ever-shrinking reservations.

The American Revolution was, for the Iroquois Confederacy, a catastrophic conflict that marked the end of an era. It dissolved their political unity, devastated their lands, and fundamentally undermined their sovereignty. Their active and complex role in the war—initially seeking neutrality, then divided by competing loyalties and strategic calculations—illustrates the multifaceted nature of the conflict and the profound impact it had on all who lived on the continent. The legacy of their sacrifices, their divisions, and their resilience continues to shape Indigenous-American relations to this day, a poignant reminder that the story of American independence is inextricably linked to the stories of the nations who called this land home long before a single shot was fired at Lexington and Concord.