The Unseen Architects of Democracy: The Iroquois Confederacy’s Enduring Constitution

In the annals of human history, few political structures can rival the longevity, sophistication, and profound influence of the Iroquois Confederacy, known to its people as the Haudenosaunee, or "People of the Longhouse." Predating the United States by centuries, this indigenous alliance forged a constitution, the Great Law of Peace (Gayanashagowa), that brought an end to generations of internecine warfare and established a model of democratic governance that continues to inspire and instruct. Its founders, the visionary Deganawida, the Peacemaker, and his eloquent disciple, Hiawatha, laid the groundwork for a society rooted in consensus, balance, and an astonishing respect for individual and collective rights.

The story of the Haudenosaunee Constitution begins not with parchment and quill, but with bloodshed and despair. For centuries, the five nations – the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca – were locked in a cycle of revenge and warfare, their populations decimated, their future uncertain. It was into this crucible of conflict that Deganawida, a Huron prophet, arrived, carrying a message of peace and unity. Born of a virgin mother, his miraculous birth and extraordinary wisdom set him apart. He preached that all human beings shared a common desire for peace and that this desire could be channeled into a collective political structure, replacing the spear with the spoken word.

Deganawida’s message, however, faced immense resistance. The spirit of vengeance was deeply ingrained. He found his most crucial ally in Hiawatha, an Onondaga chief consumed by grief after the loss of his family to the very feuds Deganawida sought to end. Deganawida, recognizing Hiawatha’s profound sorrow, performed a ceremony of condolence, using wampum beads to "wipe the tears" from his eyes, "open his ears," and "clear his throat," thereby restoring his ability to reason and speak. This act of spiritual and psychological healing became a cornerstone of the Haudenosaunee peace process, a ritual to address the trauma of loss before any political deliberation could begin.

Together, the Peacemaker and Hiawatha embarked on a monumental task: convincing the warring nations to lay down their arms and embrace a new way of life. Their efforts culminated in the establishment of the Great Law of Peace, a complex, unwritten constitution passed down orally through generations and later recorded in wampum belts – intricate arrangements of shell beads that served as mnemonic devices and sacred texts.

At the heart of the Great Law was the symbolic "Tree of Peace," a towering white pine under which the nations buried their weapons. An eagle perched atop the tree, ever vigilant, watching for any threat to the Confederacy. The roots of this tree spread in the four cardinal directions, inviting other nations to join the peace. This powerful imagery encapsulated the essence of the Haudenosaunee vision: a commitment to enduring peace, protected by vigilance, and open to all who would embrace its principles.

The Gayanashagowa established a sophisticated federal system, predating modern concepts of federalism by centuries. Each of the original five nations retained its sovereignty over internal affairs but delegated certain powers to a Grand Council of Chiefs, known as Sachems. When the Tuscarora nation joined in the early 18th century, the Confederacy became known as the Six Nations.

The Grand Council was composed of 50 Sachems, each representing specific clans and nations. The Onondaga, strategically located at the center, were designated the "Firekeepers," responsible for hosting the Grand Council meetings and guiding the deliberations. The Mohawk and Seneca were the "Elder Brothers," while the Oneida and Cayuga were the "Younger Brothers." This structured seating arrangement and a prescribed speaking order ensured that all voices were heard and that decisions were arrived at through a deliberate, painstaking process of consensus.

A truly remarkable feature of the Haudenosaunee Constitution was its unique system of checks and balances and the profound role of women. Unlike many societies of its time, Haudenosaunee society was matrilineal. Clan identity, property, and even leadership succession passed through the mother’s line. The Clan Mothers, elder women of great wisdom and experience, held immense power. They were responsible for nominating and, crucially, for deposing the Sachems. If a Sachem failed to uphold the Great Law, acted selfishly, or lost the confidence of his people, the Clan Mothers could "take away his deer antlers" – the symbolic headgear of his office – effectively removing him from power. This power ensured that leaders remained accountable to their communities and were always guided by the principles of peace and righteousness.

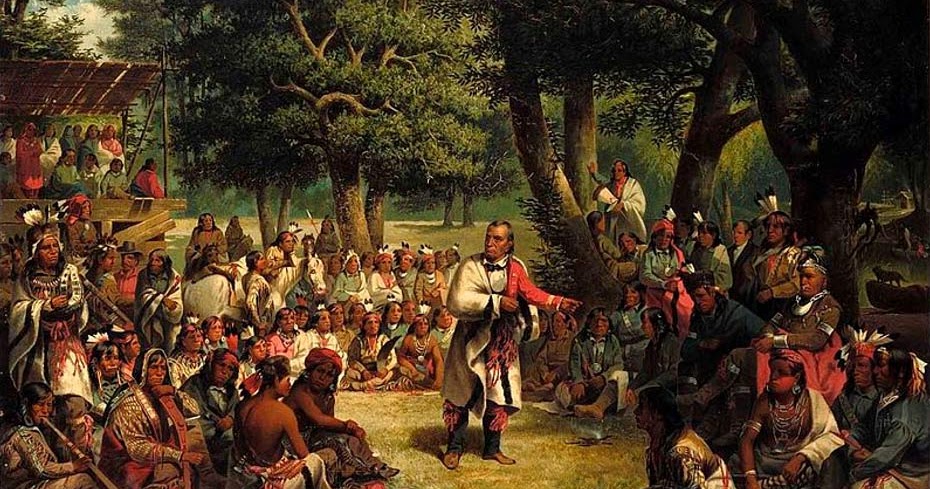

The decision-making process within the Grand Council was a model of patient deliberation. Proposals would move from the Younger Brothers to the Elder Brothers, then to the Firekeepers for review and, finally, back through the nations for approval. Unanimity was the goal, not a simple majority. This often meant extensive debate, persuasion, and a willingness to "endure the journey of deliberation" until all concerns were addressed and a consensus emerged. This process, while slow, ensured that decisions were deeply considered, widely accepted, and truly represented the collective will of the people, fostering a strong sense of unity and shared purpose.

The core principles enshrined in the Great Law of Peace were:

- Righteousness (Skennen): Justice, fairness, and a commitment to moral conduct.

- Health (Karihwiiyo): Not just physical well-being, but mental and spiritual sanity, implying sound judgment and reason.

- Power (Ka’shastensera): The authority of civil law, backed by the united will of the people, to ensure peace and order, replacing the arbitrary power of individual chiefs or warriors.

These principles formed the bedrock of a society that prioritized collective welfare over individual ambition, peace over war, and reasoned discourse over violent confrontation.

The influence of the Iroquois Confederacy extends far beyond its own borders. During the colonial period, European observers like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were deeply impressed by the Haudenosaunee’s political organization and the personal liberty enjoyed by its citizens. Franklin, in particular, urged the fledgling American colonies to emulate the Iroquois model, famously remarking, "If six Nations of ignorant savages are capable of forming such a Union, how much more practicable it must be for a like Union of a greater Number of English Colonies."

While the precise degree of direct influence on the U.S. Constitution remains a subject of academic debate, the parallels are undeniable. Concepts such as federalism, the separation of powers, checks and balances, and the idea of popular sovereignty resonate strongly with the Haudenosaunee system. In 1988, the U.S. Senate passed Resolution 331, formally acknowledging "the contribution of the Iroquois Confederacy of Nations to the development of the United States Constitution."

Today, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy remains a living, breathing political entity. Its Grand Council continues to meet, its Clan Mothers continue to hold sway, and the Great Law of Peace continues to guide its people. Despite centuries of colonial encroachment, disease, and attempts at forced assimilation, the spirit of Deganawida and Hiawatha endures.

The Iroquois Confederacy stands as a powerful testament to indigenous ingenuity and political wisdom. Its founders, driven by a profound desire for peace, crafted a constitutional framework that fostered unity, ensured accountability, and championed democratic principles long before the term "democracy" gained widespread currency in the Western world. The Great Law of Peace is not merely an ancient historical artifact; it is a vibrant, living legacy, offering timeless lessons in governance, diplomacy, and the enduring human quest for a just and peaceful society.