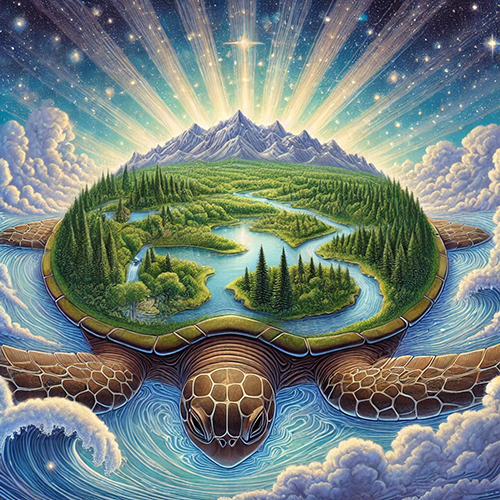

Ancient Roots, Future Solutions: Indigenous Climate Leadership on Turtle Island

The drumbeat of the climate crisis echoes across Turtle Island, the Indigenous name for North America. From unprecedented wildfires scorching ancient forests to relentless droughts parching vital farmlands and rising sea levels threatening coastal communities, the impacts are undeniable and accelerating. Yet, amidst the urgency and despair, a powerful, millennia-old wisdom offers not just resilience, but a profound blueprint for a sustainable future: Indigenous solutions. These are not novel concepts but time-tested practices, rooted in deep ecological knowledge and a reciprocal relationship with the land, that are proving indispensable in mitigating, adapting to, and even reversing the damage of a rapidly changing climate.

For too long, the dominant Western paradigm has viewed nature as a resource to be exploited, leading directly to the ecological imbalances we now face. Indigenous worldviews, in stark contrast, understand humanity as an integral part of an interconnected web of life, where every action has consequences and responsibilities extend to future generations. This fundamental difference is the bedrock of Indigenous climate leadership, offering a holistic, community-driven, and land-based approach that stands in stark opposition to the often-fragmented and technology-centric solutions proposed by colonial systems.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), passed down through generations of observation, experience, and spiritual connection, is at the heart of these solutions. TEK encompasses an understanding of complex ecosystems, weather patterns, plant and animal behaviors, and sustainable resource management techniques honed over thousands of years. It’s a dynamic body of knowledge that continues to evolve, adapting to new challenges while maintaining core principles of respect and reciprocity. As Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer (Potawatomi), a distinguished professor and author of Braiding Sweetgrass, eloquently states, "Knowledge is a gift that must be given away to grow." Indigenous communities are now sharing this gift, not just for their own survival, but for the benefit of all.

One of the most powerful and immediate Indigenous solutions to the climate crisis on Turtle Island lies in forest management and wildfire prevention. For millennia, Indigenous peoples across what is now California, the Pacific Northwest, and other forested regions employed prescribed burning – cultural burns – to manage landscapes. These controlled, low-intensity fires mimicked natural fire regimes, reducing fuel loads, promoting biodiversity, enhancing plant growth, and creating fire-resilient ecosystems. However, a century of fire suppression policies by colonial governments, often accompanied by the forcible removal of Indigenous land managers, led to an unnatural accumulation of dense undergrowth, turning once-healthy forests into tinderboxes.

Today, Indigenous communities like the Karuk, Yurok, and Hupa in California are reclaiming their ancestral fire practices, working with state and federal agencies to reintroduce cultural burning. This isn’t just about reducing catastrophic wildfires; it’s a multi-faceted climate solution. Healthy, fire-adapted forests are more resilient to drought and pests, sequester more carbon, and support greater biodiversity. Margo Robbins (Yurok), co-founder of the Cultural Fire Management Council, emphasizes the profound impact: "When we burn, the water runs clearer, the salmon runs are better, the deer are healthier. It’s all connected." This integrated approach demonstrates how ecological health directly contributes to climate resilience and ecosystem services.

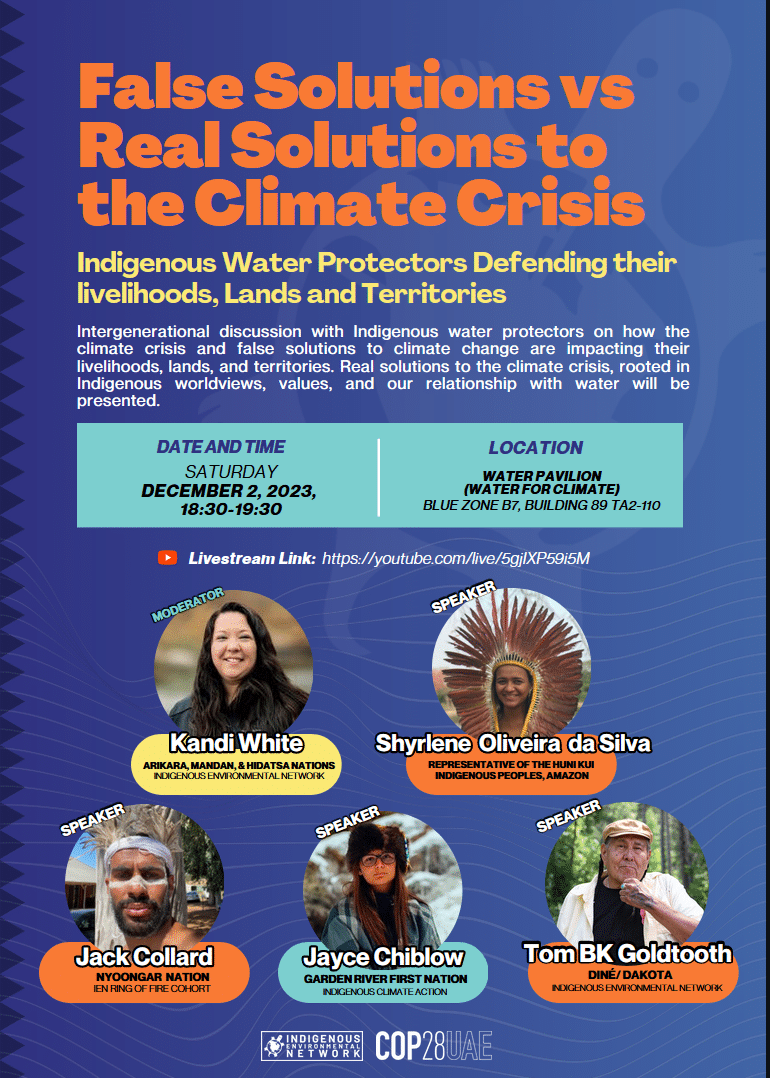

Water protection and restoration represent another critical pillar of Indigenous climate action. From the sacred struggles at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline to the ongoing efforts of Anishinaabe Water Walkers, Indigenous peoples are at the forefront of defending fresh water sources from pollution and overuse. Climate change exacerbates water scarcity and contamination through prolonged droughts, increased evaporation, and extreme weather events that overwhelm infrastructure. Indigenous communities, often the first to feel these impacts, are responding with innovative, land-based solutions.

Many Indigenous nations are implementing sophisticated water monitoring programs, combining TEK with modern science to assess water quality and quantity. They advocate for watershed-level management, recognizing the interconnectedness of all water bodies from source to sea. The Mi’kmaq, for example, are working to restore traditional eelgrass beds, which act as natural carbon sinks, filter water, and provide critical habitat. Furthermore, Indigenous legal frameworks, which often recognize water as a living entity with inherent rights, challenge the Western concept of water as a commodity, advocating for policies that prioritize ecological health and community access over industrial exploitation.

Sustainable food systems and food sovereignty are also crucial Indigenous contributions to climate resilience. Industrial agriculture is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. Indigenous food systems, conversely, are designed for long-term sustainability, promoting biodiversity, soil health, and local food security. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) tradition of "Three Sisters" planting (corn, beans, squash) is a prime example: corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash shades the ground, retaining moisture and suppressing weeds. This symbiotic relationship reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, enhancing soil carbon sequestration and overall ecosystem health.

Across Turtle Island, Indigenous communities are revitalizing traditional foodways – cultivating ancestral crops, restoring buffalo herds to grasslands (which promotes soil health and biodiversity), and practicing sustainable hunting and fishing. These efforts not only reduce the carbon footprint associated with industrial food production and transportation but also strengthen community resilience against climate-induced disruptions to the global food supply. The Indigenous Seed Keepers Network, for instance, works to preserve and revitalize heirloom seeds, protecting genetic diversity vital for adapting to changing climates.

The concept of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) is gaining significant traction, particularly in Canada, as a powerful tool for biodiversity conservation and climate mitigation. IPCAs are lands and waters where Indigenous peoples have primary responsibility for protecting and managing ecosystems, often combining traditional laws and governance with contemporary conservation science. These areas are not just about setting aside land; they are about restoring relationships with the land, fostering cultural revitalization, and supporting Indigenous self-determination.

Studies consistently show that Indigenous-managed lands have higher biodiversity and better ecological outcomes than state-managed protected areas. Indigenous Guardians programs, where community members are trained to monitor, manage, and protect their traditional territories, are at the forefront of this work. They monitor wildlife populations, track climate impacts, restore degraded habitats, and ensure sustainable resource use. By supporting the establishment and resourcing of IPCAs, governments can leverage Indigenous knowledge and stewardship for immense climate and biodiversity benefits. Indeed, Indigenous peoples, though comprising less than 5% of the global population, manage or hold tenure over a quarter of the world’s land surface, which harbors 80% of the world’s biodiversity.

Despite the profound efficacy of these solutions, Indigenous communities often face significant barriers. Centuries of colonialism have resulted in land dispossession, cultural suppression, and chronic underfunding, hindering their ability to implement and scale these solutions. Furthermore, Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change, often residing in vulnerable regions and lacking adequate infrastructure or resources for adaptation.

The path forward demands a fundamental shift: a move away from tokenistic consultation towards genuine partnership, respect, and Indigenous self-determination. This includes upholding treaty rights, returning ancestral lands, and providing equitable funding for Indigenous-led initiatives. It means recognizing Indigenous governance structures and legal systems as legitimate and essential for effective land and water management.

The solutions offered by Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island are not simply "alternative" approaches; they are foundational, holistic, and deeply effective pathways to address the climate crisis. They remind us that the health of the land is inextricably linked to the health of the people, and that true sustainability emerges from a relationship of respect, reciprocity, and responsibility. As the world grapples with the escalating climate emergency, listening to and empowering Indigenous voices is not merely an act of justice, but a critical imperative for the survival and well-being of all. Their ancient wisdom, rooted in thousands of years of stewardship, offers not just hope, but a tangible, proven roadmap to a livable future on Turtle Island and beyond.