Reclaiming Sovereignty: Indigenous Self-Governance on Turtle Island

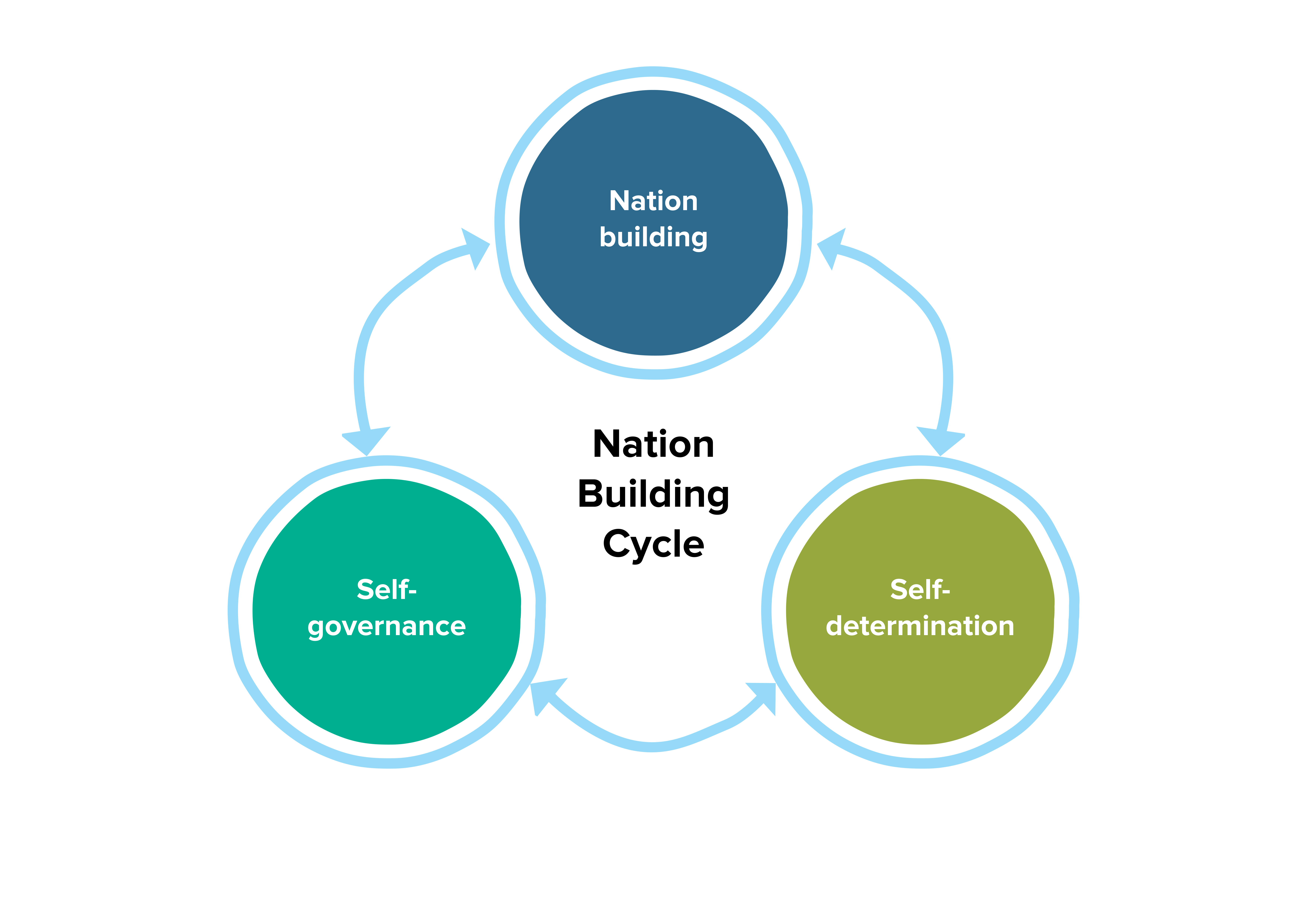

On Turtle Island, the ancient and enduring concept of Indigenous self-governance is not merely a political aspiration but a vibrant, evolving reality, a testament to resilience and the inherent right of nations to determine their own futures. Far from a monolithic ideal, self-governance manifests in a rich tapestry of models, each reflecting distinct cultural traditions, historical contexts, and specific agreements with colonial states. These diverse approaches, from revitalized traditional systems to modern treaty agreements, represent a profound movement towards decolonization, nation-building, and a more just relationship with the settler societies that surround them.

At its core, Indigenous self-governance is the exercise of inherent sovereignty—the right of Indigenous nations to govern themselves according to their own laws, cultures, and traditions. This is not a right granted by settler governments but an inherent one, pre-existing and never fully extinguished by colonization. While often articulated through contemporary legal and political frameworks, its roots lie deep in millennia of established governance structures, sophisticated legal systems, and intricate diplomatic protocols that characterized life on Turtle Island long before European arrival.

The Shadow of Colonialism and the Spark of Resurgence

For centuries, colonial policies aggressively sought to dismantle these Indigenous governance systems. In Canada, the Indian Act (1876) centralized power in the federal government, imposing foreign administrative structures, outlawing traditional ceremonies, and denying basic rights. Similarly, in the United States, policies of forced assimilation, the Dawes Act (1887), and the termination era aimed to dissolve tribal land bases and governmental authority. These policies inflicted immense damage, severing cultural ties, undermining economies, and creating profound social challenges that continue to reverberate today.

However, Indigenous peoples never ceased to assert their sovereignty. From the earliest days of contact, through armed resistance, peaceful protest, and relentless advocacy, the flame of self-determination flickered, refusing to be extinguished. The mid-20th century saw a resurgence, fueled by growing political consciousness, legal challenges, and international human rights movements. Landmark legal victories, such as the Calder v. British Columbia case (1973) in Canada which affirmed the existence of Aboriginal title, and the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975) in the U.S., provided crucial legal and policy foundations for the re-establishment of Indigenous authority.

Internationally, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted in 2007 and increasingly embraced by Canada and the U.S., provides a universal framework. Article 3 states unequivocally: "Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development." This declaration underscores that self-governance is not a concession but a fundamental human right.

Diverse Models in Action: A Mosaic of Sovereignty

The models of Indigenous self-governance across Turtle Island are as diverse as the nations themselves, reflecting unique historical trajectories, cultural values, and pragmatic adaptations.

1. Revitalized Traditional Governance: The Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Perhaps one of the most enduring and influential examples of traditional governance is the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, encompassing the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations. Governed by the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa), an oral constitution predating European contact by centuries, the Confederacy operates through a sophisticated system of checks and balances, consensus-building, and clan mothers’ authority. Their traditional government continues to function independently, maintaining its own passports, legal systems, and diplomatic relations, often asserting its sovereignty directly with international bodies, bypassing Canadian and U.S. governments. The Haudenosaunee system is often cited as an inspiration for early American democratic thought, a testament to its sophistication.

2. Modern Treaty and Self-Government Agreements: The Nisga’a Nation

In Canada, modern treaties and self-government agreements represent a significant pathway to self-determination. The Nisga’a Final Agreement, signed in 1998, is a landmark example. This treaty recognized Nisga’a title to over 2,000 square kilometers of land in northwestern British Columbia, along with ownership of forest resources, fisheries, and subsurface resources. Crucially, it established the Nisga’a Lisims Government, granting the nation broad jurisdiction over a wide range of areas including education, child and family services, health, language and culture, and justice. The Nisga’a Nation now collects taxes, manages its own resources, and delivers services, operating effectively as "a nation within Canada," as many describe it. This model emphasizes a comprehensive transfer of powers, moving beyond the Indian Act framework.

3. Public Government Models: Nunavut Territory

Unique among self-governance models is Nunavut, a vast territory in Arctic Canada created in 1999. While not exclusively an Indigenous government, it is a public government where Inuit form the majority of the population and hold most elected positions. This arrangement emerged from the largest Indigenous land claim settlement in Canadian history. Nunavut provides a model where self-determination is achieved through the creation of a new jurisdiction within the federal system, allowing Inuit to shape the policies and programs that directly affect their lives across all residents of the territory, not just enrolled members. It demonstrates how self-governance can be pursued through the establishment of new, Indigenous-led political entities.

4. Asserting Inherent Rights: The Mi’kmaq Netukulimk Fishery

Some nations are asserting their inherent and treaty rights without needing new agreements, often leading to direct confrontations with settler governments. In Nova Scotia, Canada, the Mi’kmaq Nation has, for decades, asserted its treaty right to a "moderate livelihood" fishery, based on the 1760-61 Peace and Friendship Treaties. Following the landmark R. v. Marshall Supreme Court of Canada decision in 1999, which affirmed this right, Mi’kmaq communities have established their own self-regulated fisheries, developing their own conservation rules, licensing systems, and economic models. This ongoing process highlights the importance of treaty implementation and the assertion of inherent economic self-sufficiency, often in the face of resistance from non-Indigenous industries and governments.

5. Judicial and Law Enforcement Self-Governance: The Navajo Nation

In the United States, the Navajo Nation (Diné) is the largest federally recognized tribe by land area and population. It operates a robust, multi-branch government with its own court system, police force, and administrative agencies. The Navajo Nation’s judicial branch, for instance, blends Western legal principles with traditional Diné common law, emphasizing restorative justice, peacemaking, and the preservation of cultural values. This integrated system allows the Nation to administer justice in a way that resonates with its cultural ethos, often leading to more effective and culturally appropriate outcomes than state or federal systems.

Key Pillars of Effective Self-Governance

Regardless of the specific model, successful Indigenous self-governance typically hinges on several critical pillars:

- Jurisdictional Control: The ability to make laws and enforce them over land, resources, education, health, child welfare, justice, and economic development.

- Economic Self-Sufficiency: Developing and managing their own economies, generating revenue, and creating opportunities for their citizens, reducing reliance on external funding.

- Cultural Revitalization: The authority to protect and promote their languages, traditions, ceremonies, and knowledge systems, which are integral to identity and well-being.

- Capacity Building: Investing in human resources, developing administrative expertise, and strengthening institutional frameworks to effectively govern.

- Accountability and Transparency: Establishing robust governance structures that are accountable to their own citizens and operate transparently.

Challenges and the Path Forward

While the progress in Indigenous self-governance is undeniable, significant challenges persist. The legacy of colonialism continues to manifest in underfunding, jurisdictional disputes with federal and provincial/state governments, and a persistent need for reconciliation. Many Indigenous nations still operate under outdated colonial legislation or face systemic barriers to exercising their full inherent rights. Internal challenges, such as developing governance structures that are both effective and culturally appropriate, also require ongoing attention.

Yet, the momentum towards self-determination is irreversible. Indigenous nations are demonstrating that when they are empowered to govern themselves, they achieve better outcomes for their communities in health, education, economic development, and cultural preservation. Studies consistently show that Indigenous-led initiatives, tailored to local needs and values, are more effective and sustainable.

As John Borrows, a leading Indigenous legal scholar, aptly notes, "Indigenous laws are not relics of the past; they are living legal traditions that offer profound insights into how we can live together in harmony with each other and the land." The unfolding tapestry of Indigenous self-governance on Turtle Island is not just about correcting historical injustices; it is about building stronger, more vibrant, and more equitable societies for all who share this land, recognizing the inherent wisdom and enduring power of Indigenous nations to chart their own course. The journey towards full sovereignty is ongoing, but the path is clear, illuminated by the resilience, determination, and profound cultural strength of Indigenous peoples.