Reclaiming Sovereignty: The Enduring Battle for Indigenous Legal Status and Self-Governance

The legal status of Indigenous Nations worldwide stands as a complex, often contested, and profoundly significant issue, representing centuries of struggle against colonial imposition and the enduring quest for self-determination. Far from being a relic of the past, the debate surrounding Indigenous sovereignty and the right to self-governance is a vibrant, active arena of legal battles, political negotiations, and cultural revitalization, fundamentally shaping the future of nations and the global landscape of human rights. This article delves into the intricacies of Indigenous Nations’ legal status and their unwavering pursuit of self-governance, exploring historical precedents, contemporary challenges, and the vital pathways to true reconciliation and equity.

At its core, the concept of Indigenous legal status revolves around inherent sovereignty – the idea that Indigenous peoples possessed and continue to possess sovereign rights predating and independent of colonial claims. These rights were not granted by colonizers but are intrinsic to their existence as distinct peoples with their own laws, territories, and governance structures. However, this inherent sovereignty has been systematically undermined, ignored, or reinterpreted by settler states, leading to a convoluted legal landscape where Indigenous nations are often treated as subordinate entities within larger national frameworks.

In the United States, for instance, the foundational legal doctrine for Indigenous nations emerged from a series of Supreme Court decisions in the early 19th century, most notably Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832). Chief Justice John Marshall, in Cherokee Nation, famously characterized Indigenous tribes as "domestic dependent nations," describing their relationship with the federal government as akin to "a ward to its guardian." This paternalistic framing, while acknowledging a distinct political existence, simultaneously curtailed their full sovereign powers, placing them under the plenary power of the U.S. Congress. While this concept has evolved, the legacy of "domestic dependent nation" status continues to influence federal Indian law, creating a unique and often challenging jurisdictional maze where tribal, state, and federal laws intersect and conflict.

Similarly, in Canada, the legal status of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples is rooted in a complex interplay of Royal Proclamations, treaties, and the Constitution Act of 1982, which affirms existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. However, historical assimilation policies, such as the Indian Act of 1876, systematically stripped Indigenous peoples of their self-governance, imposed foreign administrative structures, and suppressed cultural practices. The struggle for self-governance in Canada has therefore largely been a battle to reclaim and implement these inherent and treaty rights, often through arduous court cases and political negotiations.

Globally, the international community has grappled with defining and upholding Indigenous rights. A monumental step forward was the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. UNDRIP, while not legally binding in the same way as a treaty, establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the Indigenous peoples of the world. Article 3 of UNDRIP unequivocally states: "Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development." This declaration serves as a powerful moral and political tool, guiding states toward respecting, protecting, and fulfilling Indigenous rights, including the right to self-governance.

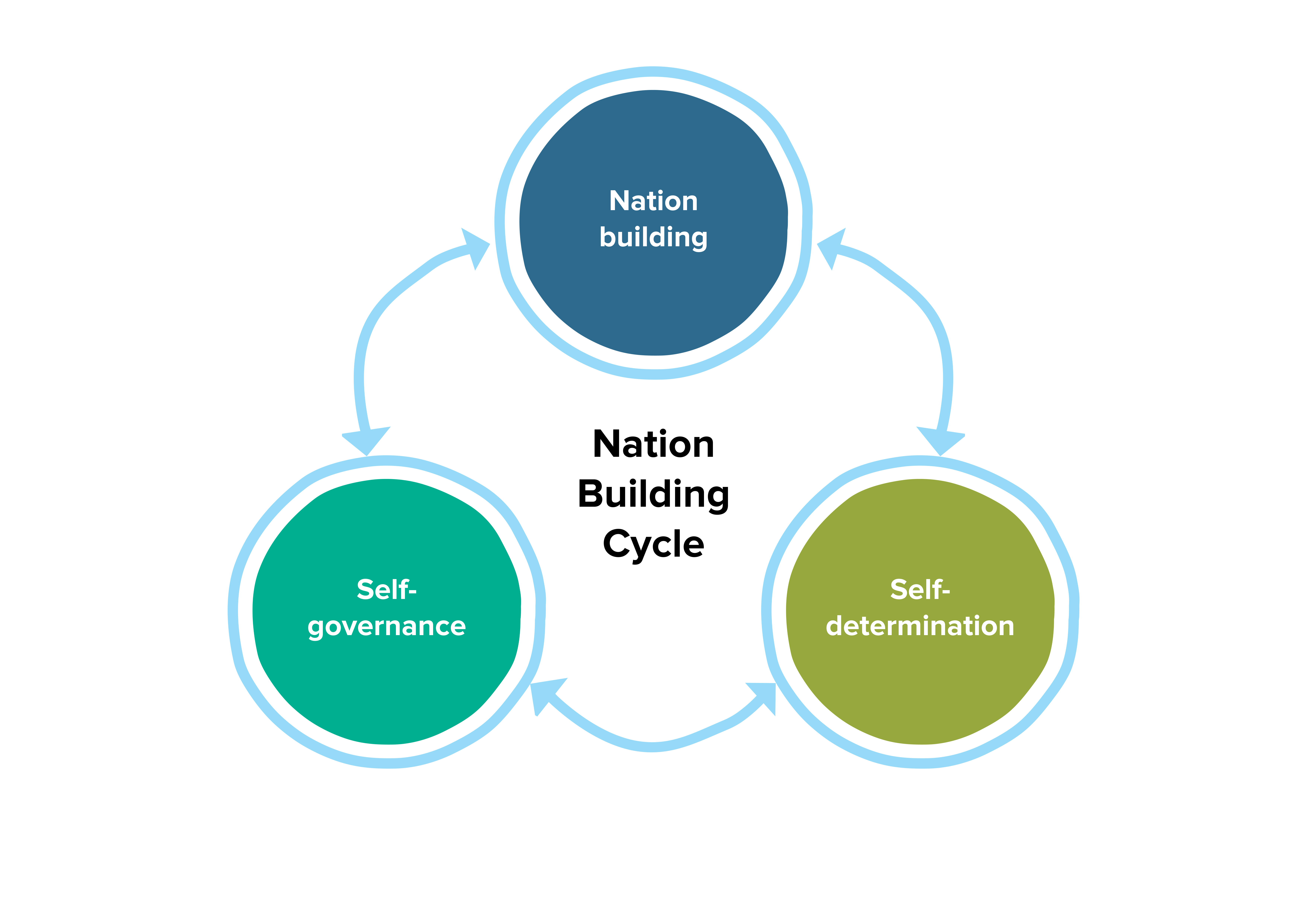

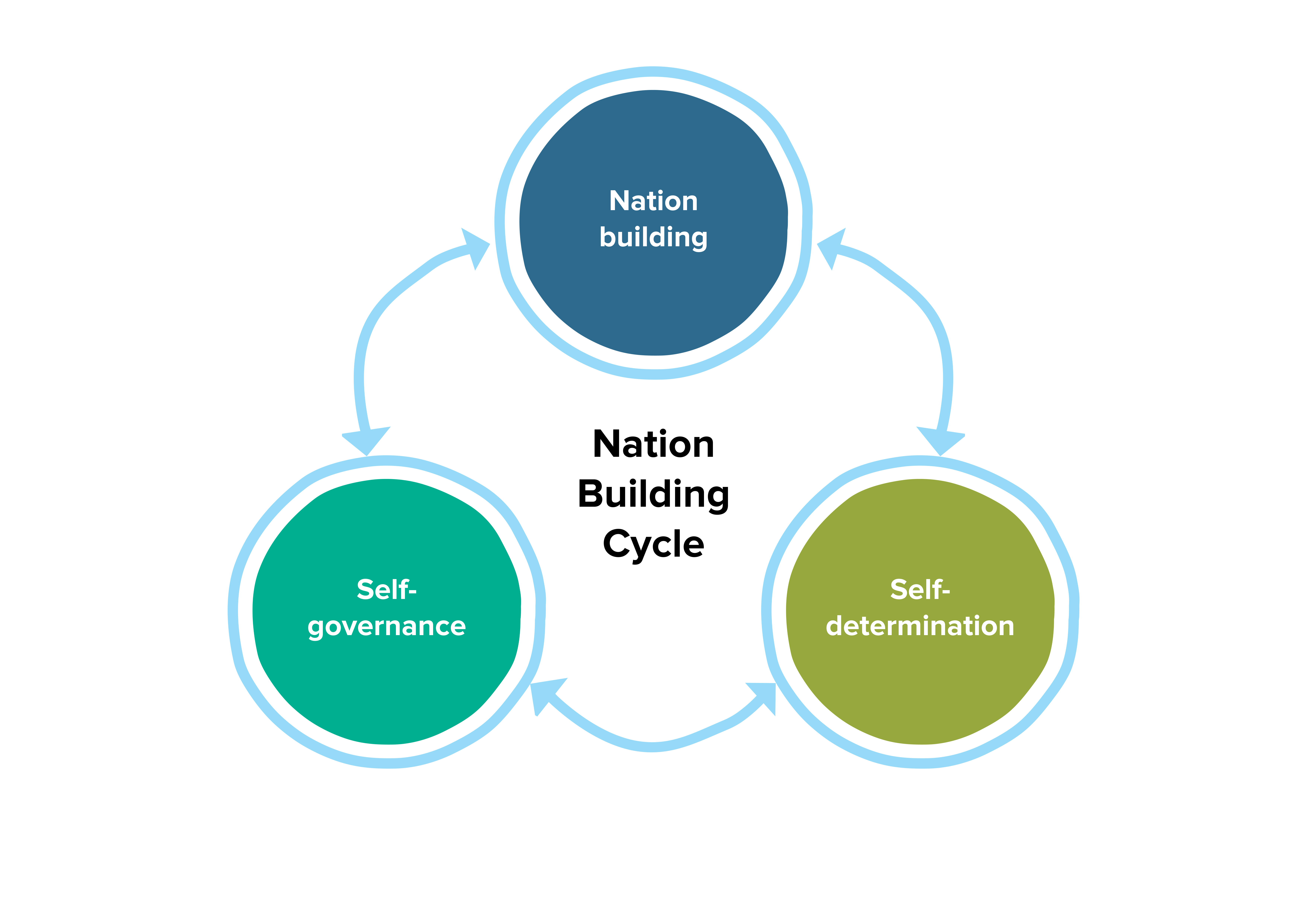

The pursuit of self-governance by Indigenous Nations is not merely an abstract legal concept; it is a practical necessity for cultural survival, economic prosperity, and social well-being. Self-governance encompasses the right and capacity of Indigenous peoples to manage their own affairs, including jurisdiction over their lands and resources, the administration of justice through their own courts and legal systems, the development of their own educational curricula, the provision of healthcare, and the fostering of their unique languages and cultures.

One of the most critical aspects of self-governance is jurisdiction over land and resources. Historically, colonial powers dispossessed Indigenous peoples of their ancestral territories, often for resource extraction, agricultural expansion, or settlement. Reclaiming and exercising control over these lands is fundamental to economic self-sufficiency and environmental stewardship. For example, many Indigenous nations are actively involved in land claim negotiations, asserting their rights to traditional territories, and developing their own resource management policies that prioritize sustainable practices informed by generations of traditional ecological knowledge. The success of some Indigenous nations in developing lucrative resource industries, such as gaming, tourism, or energy, demonstrates how self-governance can lead to significant economic development, allowing them to fund essential services and infrastructure for their communities.

Another vital component is the establishment and operation of Indigenous justice systems. For centuries, Indigenous peoples were subjected to colonial legal frameworks that often failed to understand or respect their traditional laws and customs, leading to disproportionate incarceration rates and systemic injustices. The re-establishment of tribal courts, customary law practices, and restorative justice initiatives represents a profound step towards healing and justice. These systems often prioritize rehabilitation, community involvement, and the restoration of harmony, reflecting deeply held cultural values that differ significantly from adversarial Western legal models.

Education and cultural revitalization are also at the heart of Indigenous self-governance. Colonial policies often aimed to eradicate Indigenous languages and cultures through residential schools or forced assimilation. Today, Indigenous nations are leading efforts to establish their own education systems, including immersion schools that teach ancestral languages, traditional knowledge, and culturally relevant curricula. These initiatives are crucial for transmitting cultural identity to younger generations, fostering a sense of pride, and reversing the intergenerational trauma caused by past policies.

Despite significant progress and the growing international recognition of Indigenous rights, the path to full self-governance remains fraught with challenges. Persistent obstacles include:

- Colonial Legacy and Paternalism: Many settler states continue to operate under a mentality that views Indigenous nations as dependent entities, rather than as co-equal partners. This often manifests in restrictive legislation, underfunding of Indigenous services, and a reluctance to fully transfer jurisdictional authority.

- Jurisdictional Disputes: The overlapping and often conflicting jurisdictions between Indigenous, provincial/state, and federal governments create legal quagmires, particularly concerning land use, resource development, and law enforcement.

- Funding Disparities: Even where self-governance agreements exist, Indigenous nations often receive inadequate funding to effectively implement their programs and services, forcing them to rely on limited resources or continued dependence on external governments.

- Resource Extraction Conflicts: Indigenous lands are frequently targeted for large-scale resource extraction projects (mining, oil, gas, logging). The tension between economic development interests and Indigenous rights to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) often leads to protracted legal battles and social unrest.

- Racism and Discrimination: Systemic racism continues to plague institutions and societies, impacting Indigenous peoples’ access to justice, healthcare, employment, and overall well-being, hindering their ability to fully exercise self-governance.

Yet, amidst these challenges, there are powerful examples of resilience and success. From the Inuit Nunangat in Canada, which exercises significant self-governance over vast Arctic territories, to the Māori in Aotearoa (New Zealand) who have achieved significant land and resource settlements and established robust self-governing entities, Indigenous nations are demonstrating the transformative power of self-determination. The Navajo Nation, the largest Indigenous territory in the United States, operates a comprehensive government with legislative, executive, and judicial branches, providing a wide array of services to its citizens and managing its vast resources. These examples underscore that when Indigenous peoples are empowered to govern themselves, they often achieve better outcomes in health, education, economic development, and cultural preservation.

The ongoing journey for Indigenous legal status and self-governance is a testament to the unwavering spirit of Indigenous peoples worldwide. It is a quest not just for legal recognition, but for the restoration of justice, the revitalization of cultures, and the forging of respectful nation-to-nation relationships. As the world increasingly grapples with issues of human rights, environmental sustainability, and social equity, understanding and supporting Indigenous self-determination becomes paramount. It represents not only a commitment to righting historical wrongs but also an investment in a more diverse, just, and sustainable global future, where the inherent rights and unique contributions of all peoples are honored and protected. The full realization of Indigenous sovereignty is not merely an Indigenous issue; it is a universal human imperative.