Guardians of the Word: How Online Dictionaries Are Forging a Future for Indigenous Languages

In a world where a language dies every two weeks, carrying with it unique ways of understanding the universe, the fight to preserve Indigenous languages has never been more urgent. For centuries, printed dictionaries were the formidable, often colonial, gatekeepers of language knowledge. Today, however, a quiet revolution is unfolding in the digital realm, as online Indigenous language dictionaries emerge as dynamic, accessible, and community-driven bastions against linguistic extinction. These digital repositories are not merely collections of words; they are living documents, cultural anchors, and powerful tools for revitalization, bridging generations and geographies to ensure that ancient voices resonate in the digital age.

The crisis facing Indigenous languages is profound. UNESCO estimates that out of the roughly 7,000 languages spoken globally, nearly half are endangered, with many facing extinction within the next century. This loss is not just linguistic; it represents an irreparable erosion of cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, unique worldviews, and collective memory. "When a language dies, it’s not just a dictionary that’s lost; it’s an entire library of knowledge about the environment, history, and human experience," says Dr. Anya Sharma, a computational linguist specializing in endangered languages. "The urgency is immense, and technology offers a lifeline that was unimaginable even a few decades ago."

Traditionally, Indigenous language dictionaries were painstaking academic endeavors, often compiled by external linguists with limited community input, resulting in static, expensive, and geographically inaccessible resources. They were often prescriptive, rather than reflective of the living, evolving nature of language. The advent of the internet, however, has fundamentally reshaped this landscape, offering unprecedented opportunities for communities to reclaim ownership and control over their linguistic heritage.

The Digital Advantage: More Than Just Words

Online Indigenous language dictionaries possess a multitude of advantages over their print predecessors, making them invaluable tools for revitalization efforts:

-

Unprecedented Accessibility: Unlike hefty print volumes confined to libraries or university archives, online dictionaries are accessible anywhere with an internet connection. This means speakers, learners, and researchers across the globe, including diaspora communities, can instantly access the language. This democratizes knowledge, breaking down geographical and socio-economic barriers.

-

Dynamic and Ever-Evolving: Print dictionaries are static snapshots. Online dictionaries, conversely, are living documents. They can be updated in real-time with new words, evolving meanings, and corrections. This dynamic nature is crucial for languages that are actively being revived or are adapting to modern contexts, allowing them to remain relevant and responsive.

-

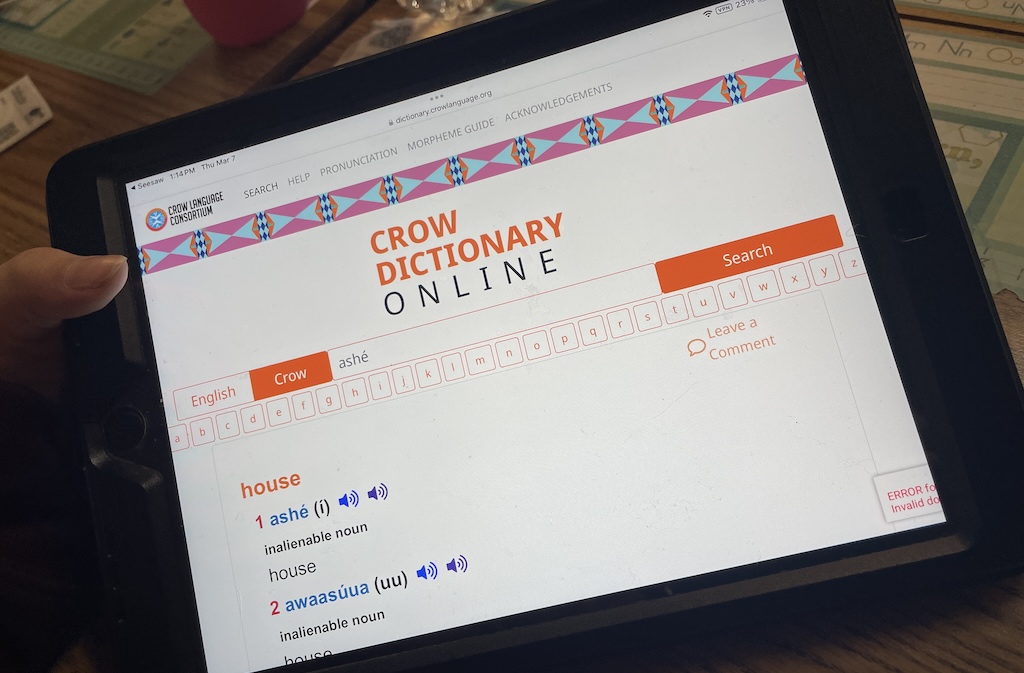

Multimedia Integration: Many Indigenous languages are primarily oral, or their writing systems are relatively recent. Online platforms can incorporate audio pronunciations, allowing learners to hear the nuances of tone and intonation directly from native speakers. Videos demonstrating cultural practices or spoken dialogues, images illustrating concepts, and even traditional songs can be embedded, providing a rich, multi-sensory learning experience that print simply cannot offer. For a language like the Squamish language (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim) in Canada, where tonal distinctions are crucial, audio is indispensable.

-

Community-Driven Ownership and Collaboration: Perhaps the most transformative aspect is the ability for Indigenous communities themselves to lead the creation and maintenance of these dictionaries. Platforms can be designed to allow elders, fluent speakers, and language learners to contribute, review, and curate content. This fosters a sense of ownership, pride, and empowers communities to define their language on their own terms, rather than relying solely on external experts. "Our language is our identity, our connection to our ancestors and our land," states Elder Joseph Red Feather of the Lakota Nation. "Having an online dictionary built by our own people, where our children can hear the words spoken by our elders, is a powerful act of sovereignty and survival."

-

Pedagogical Powerhouse: For language learners, online dictionaries are invaluable. They can be integrated into language learning apps, curricula, and educational programs. Search functions allow for quick look-ups, while features like example sentences and grammatical notes provide deeper understanding. They become foundational resources for developing teaching materials, from basic vocabulary lists to complex grammatical structures.

Navigating the Challenges

Despite their immense potential, the creation and sustainability of online Indigenous language dictionaries are not without significant challenges:

- Funding and Resources: Developing and maintaining high-quality digital platforms requires substantial financial investment for technical infrastructure, server hosting, software development, and the time of linguists, cultural experts, and community members. Sustained funding is often difficult to secure.

- Technical Expertise: Many Indigenous communities may lack the technical expertise for web development, database management, and digital archiving. Training and capacity building are crucial, but often overlooked.

- Data Collection and Ethical Considerations: The process of collecting linguistic data must be done respectfully and ethically, ensuring proper consent, intellectual property rights, and community ownership. Decisions about orthography (writing systems), dialect representation, and cultural sensitivity require careful navigation.

- Digital Divide: While access to the internet is expanding, many remote Indigenous communities still face limited or no internet connectivity, or lack access to necessary devices, creating a digital divide that can hinder accessibility.

- Long-Term Preservation: Digital information is vulnerable to technological obsolescence and data loss. Robust long-term digital preservation strategies are essential to ensure these invaluable resources remain accessible for future generations.

Success Stories and the Road Ahead

Across the globe, inspiring projects are demonstrating the transformative power of online Indigenous language dictionaries.

One of the most prominent examples is FirstVoices.com, a suite of web-based tools and services designed to help Indigenous communities document and revitalize their languages. Launched in Canada, FirstVoices hosts dictionaries, phrasebooks, and alphabets for over 100 Indigenous languages, complete with audio pronunciations from fluent speakers. Its community-driven model empowers local language teams to manage their own content, ensuring cultural accuracy and relevance. The platform has become a cornerstone for language education and preservation in Canada.

In Australia, the Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi (KWP) project has been instrumental in the revitalization of the Kaurna language, the traditional language of the Adelaide Plains. Their online dictionary is a central component, providing not just words but also example sentences, audio, and cultural context, making it a key resource for a language that was once considered dormant.

Global platforms like Wiktionary also host entries for numerous Indigenous languages, leveraging a volunteer community to build out resources, though these projects often require careful oversight to ensure accuracy and respect for cultural nuances. Smaller, community-specific initiatives, often developed with academic partners, are also blossoming, tailored to the unique needs of individual linguistic groups.

The future of online Indigenous language dictionaries is bright but requires sustained commitment. Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP) hold immense promise for assisting in transcription, translation, and even generating learning exercises, though these technologies must be applied thoughtfully and ethically, always under the guidance of Indigenous communities. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) could create immersive language learning environments, connecting learners to words in their ancestral landscapes.

Ultimately, these digital dictionaries are far more than mere linguistic tools; they are powerful symbols of resilience, cultural reclamation, and the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. They represent a fundamental shift in how language preservation is approached – from externally imposed documentation to internally driven revitalization. By harnessing the power of the internet, Indigenous communities are not just saving words; they are securing the future of their unique cultures, ensuring that their ancient wisdom, stories, and identities continue to thrive for generations to come. As Elder Red Feather wisely noted, "Every word we put online is a seed planted for our future. It tells our children, and the world, that we are still here, and our language will live on."