Threads of Belonging: Unraveling Indigenous Family Structures and Marriage Regulations

In a world increasingly defined by individualism, the intricate tapestry of Indigenous family structures and marriage regulations stands as a profound testament to the power of collective belonging, ancestral wisdom, and the enduring human spirit. Far from the simplistic notions often portrayed, these systems are sophisticated frameworks that govern social order, spiritual well-being, and the very survival of communities. They are not monolithic; like the diverse landscapes Indigenous peoples inhabit, their kinship systems and marital customs vary widely across continents and cultures, yet they share a fundamental commitment to interconnectedness that offers invaluable lessons for all societies.

To truly understand Indigenous family and marriage is to step beyond the Western nuclear model and embrace a universe where kinship extends far beyond biological ties. For the over 370 million Indigenous people worldwide, belonging to some 5,000 distinct groups in 90 countries, family is a vast web of relations—social, spiritual, and economic—that defines one’s identity, responsibilities, and place in the world. This is often encapsulated in the Lakota phrase, "Mitákuye Oyásʼiŋ" or "All My Relations," a concept that acknowledges the interconnectedness of all living things, including the land, animals, and ancestors.

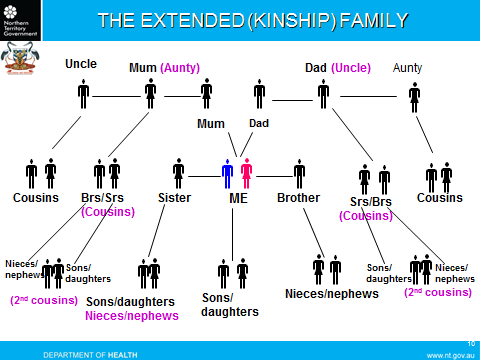

At the heart of many Indigenous societies lies the kinship system, a complex organizational structure that dictates who you are related to, how you address them, and what your mutual obligations entail. These systems can include moieties, clans, or skin names, which classify individuals into specific groups and determine appropriate social interactions, including marriage partners. An aunt, for instance, might be seen as a co-parent, holding equal responsibility for a child’s upbringing, while grandparents often serve as primary educators and cultural knowledge keepers, weaving stories, histories, and values into the fabric of daily life. Children, in turn, are not merely individuals but inheritors of ancient traditions, vital links in a chain stretching from the past to the future. This collective responsibility fosters a profound sense of community, ensuring that no individual stands alone and that the well-being of the group takes precedence.

Marriage within these contexts is rarely a mere romantic union between two individuals. Instead, it is a sacred contract, a strategic alliance that weaves families, clans, and even entire communities together. The regulations governing marriage are meticulously crafted, serving crucial functions such as preventing incest (often broadly defined to include distant relatives within the same kinship group), strengthening social bonds, and ensuring the continuity of cultural practices and knowledge.

One of the most common regulations is exogamy, the practice of marrying outside one’s specific social group, such as a clan or moiety. This rule is not arbitrary; it serves to broaden genetic diversity, forge alliances between distinct groups, and prevent the concentration of power within a single lineage. For example, among many Australian Aboriginal groups, complex "skin name" systems dictate who can marry whom, ensuring that individuals marry into appropriate, non-related lines. Conversely, some groups might practice a form of endogamy, encouraging marriage within a broader linguistic or cultural group to preserve shared identity and traditions, while still adhering to exogamous rules at the clan level.

Arranged marriages, often misunderstood through a Western lens, were (and in some places, still are) a common feature of Indigenous societies. Far from being forced, these unions were typically the result of careful negotiation and consideration by elders and family leaders, often with the consent of the individuals involved, particularly as they matured. The rationale was deeply pragmatic and communal: to ensure cultural continuity, economic stability, and the harmonious integration of families. Elders, with their vast experience, would assess compatibility not just between individuals, but between their respective families, ensuring that the union would strengthen the collective. These marriages were seen as a commitment not just to a spouse, but to the future of the community, safeguarding heritage and resource sharing.

Traditional marriage ceremonies themselves were incredibly diverse, reflecting the unique spiritual and cultural landscapes of each nation. They often involved elaborate rituals, spiritual blessings, gift-giving (which could include resources like blankets, furs, or ceremonial items, exchanged to solidify the union and demonstrate respect between families), and community feasts. These ceremonies were not just celebrations but powerful affirmations of identity, social order, and the sacred bond between individuals, their families, and the land. Among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people, for instance, the roles of Clan Mothers in guiding marriage and family life were paramount, underscoring the deep respect for matriarchal wisdom in many Indigenous societies.

However, the rich tapestry of Indigenous family structures and marriage regulations faced a brutal assault with the advent of colonialism. European colonizers, viewing Indigenous practices as "primitive" or "savage," systematically imposed their own legal, religious, and social norms. The forced assimilation policies, particularly through residential schools and the criminalization of traditional ceremonies, tore families apart, disrupted kinship systems, and replaced communal values with individualistic ideals. Children were forbidden to speak their languages, practice their cultures, or even know their own families, leading to generations of trauma and the erosion of traditional knowledge.

Yet, despite centuries of oppression, Indigenous peoples have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Many communities went underground with their practices, adapting and resisting, ensuring that the threads of belonging were never fully severed. Today, there is a powerful global movement to revitalize and reclaim these ancient traditions. This includes the resurgence of traditional languages, the re-establishment of cultural ceremonies, and the reassertion of Indigenous laws and governance, which inherently include family and marriage protocols.

A notable example of Indigenous inclusivity, often suppressed by colonial norms, is the concept of Two-Spirit individuals. Found in many North American Indigenous cultures, "Two-Spirit" is an umbrella term referring to people who embody both masculine and feminine spirits, often holding sacred roles as healers, visionaries, or mediators. Their identities, which include diverse gender expressions and sexual orientations, were traditionally honored and integrated into family and community structures, challenging rigid Western binaries and underscoring the inherent flexibility and acceptance within many pre-colonial Indigenous societies. The re-emergence of Two-Spirit identities is a powerful reclamation of Indigenous understandings of gender and sexuality, demonstrating the holistic nature of Indigenous kinship.

In contemporary times, Indigenous communities face new challenges in upholding their traditional family structures and marriage regulations. The impact of intermarriage with non-Indigenous people, the complexities of navigating traditional laws within modern legal systems, and the ongoing socio-economic disparities inherited from colonialism all present significant hurdles. Yet, the foundational principles endure. The emphasis on collective well-being, the respect for elders, the intricate web of responsibilities, and the sacred connection to land remain vital for identity, healing, and cultural preservation.

The lessons embedded within Indigenous family structures and marriage regulations are profound. They speak to the power of community over individualism, the wisdom of ancestral guidance, and the deep, spiritual connection between humans and the natural world. As Indigenous nations continue their journey of self-determination and cultural revitalization, they offer a powerful reminder that family is not just about who you are related to by blood, but who you are connected to by spirit, responsibility, and the enduring threads of belonging. By understanding and respecting these intricate systems, we not only honor Indigenous sovereignty but also gain invaluable insights into building more resilient, compassionate, and interconnected societies for all.