Indigenous Cosmology and Creation Time Concepts: A Tapestry of Living Narratives

Indigenous cosmologies and their intricate creation time concepts offer profound insights into humanity’s relationship with the universe, transcending mere origin stories to articulate comprehensive worldviews. Far from static myths, these narratives are dynamic, living traditions that inform social structures, ethical frameworks, environmental stewardship, and individual identity. They challenge linear, anthropocentric Western paradigms, presenting instead a reality where time is cyclical or ever-present, creation is an ongoing process, and all life is interconnected in a sacred web.

At the heart of Indigenous cosmology lies a holistic understanding of existence. The universe is not a collection of inanimate objects governed by impersonal laws, but a living, breathing entity imbued with spirit, consciousness, and relationship. Every element – from mountains and rivers to animals, plants, and celestial bodies – possesses an inherent sacredness and plays an active role in the cosmic drama. This relational worldview means that humans are not separate from nature, but an integral part of an extended family, bound by kinship to all beings.

Creation Time: Not a Distant Past, but an Ever-Present Reality

One of the most significant distinctions between Indigenous and many Western creation narratives lies in the concept of "creation time." For many Indigenous peoples, creation is not a singular, completed event relegated to a distant past, but a continuous, living process that underpins the present and shapes the future. This "sacred time" or "ancestral time" is not merely historical; it is a dimension that can be accessed and re-experienced through ceremony, ritual, storytelling, and connection to specific sacred sites.

A quintessential example is the Aboriginal Australian concept of "Dreamtime" (or "The Dreaming"). This is not a dream in the Western sense, nor is it simply a historical epoch. Instead, it is a meta-temporal realm where the Ancestral Beings created the land, its features, laws, and all living things. These Ancestral Beings, often appearing as animal-human figures, traversed the landscape, singing the world into existence, leaving behind their spiritual essence and their paths – the "songlines" – which serve as navigational maps, cultural archives, and spiritual conduits. The Dreamtime is both the ancient past and the eternal present; its power continues to reside in the land, its creatures, and the ceremonies performed by Indigenous peoples today. To "live in the Dreaming" is to live in accordance with these ancestral laws and to maintain the delicate balance established during creation.

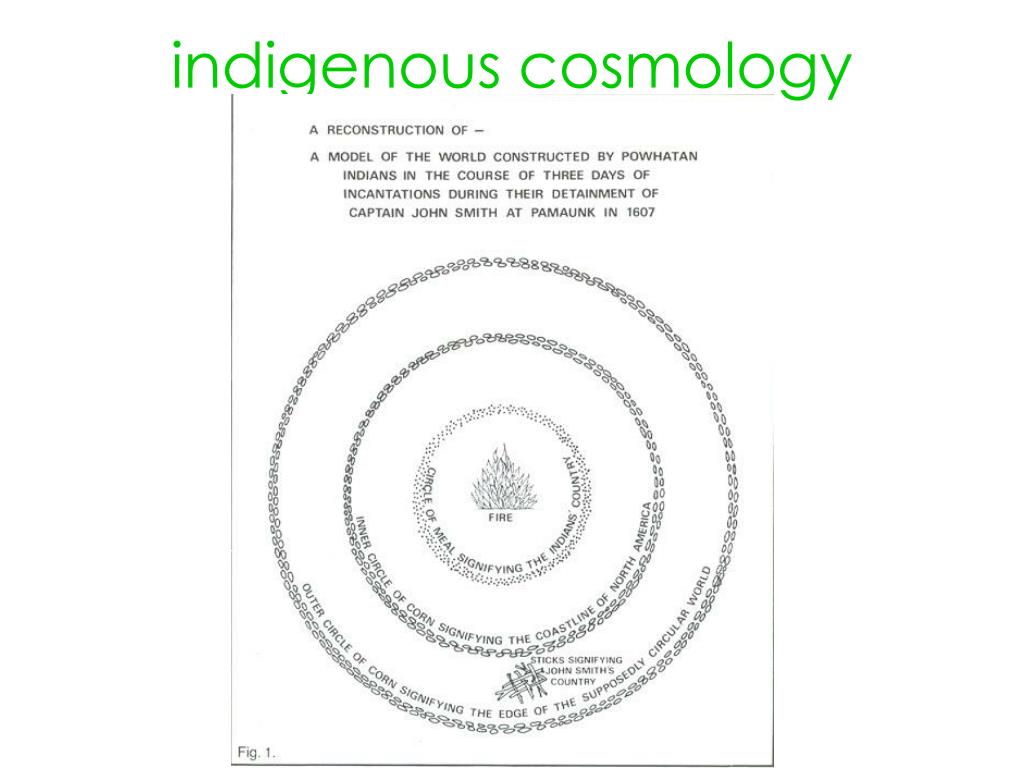

Similarly, many North American Indigenous traditions speak of an "Ancestral Time" or "First Time" when the world was being shaped, and the foundational principles of existence were established. For the Lakota, the concept of Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery, embodies the ultimate creative force, often manifested through the sacred pipe ceremonies and vision quests that connect individuals to this foundational spiritual power. The phrase "Mitakuye Oyasin" – "All My Relations" – encapsulates this deep interconnectedness, acknowledging kinship with all beings and the spiritual threads that bind them back to the moment of creation.

Diverse Creation Narratives: Themes and Meanings

While sharing common threads of interconnectedness and a living creation time, Indigenous creation narratives are incredibly diverse, reflecting the unique landscapes, cultures, and epistemologies of each nation. They are not singular, monolithic stories but a rich tapestry of localized narratives.

One common motif is the Earth Diver myth, prevalent among many Northeastern Woodlands and Great Lakes tribes (e.g., Anishinaabe, Iroquois). In these stories, often after a great flood, a cultural hero (sometimes an animal like a muskrat or beaver) dives into the primordial waters to retrieve a handful of earth from which the new world is formed, often on the back of a giant turtle. The Iroquois Confederacy’s "Sky Woman" narrative tells of Aataentsic (or Sky Woman) falling from the Sky World, landing on the back of a turtle, and with the help of various animals, creating the land we know. These stories emphasize cooperation, resilience, and the life-giving power of even the smallest creatures.

Another type is the Emergence myth, found among Southwestern peoples like the Hopi and Navajo. These narratives describe humanity’s journey through a series of underworlds or previous worlds, each imperfect, until they emerge into the current, fourth (or fifth) world. Each emergence marks a stage of spiritual and cultural development, teaching lessons about balance, community, and the consequences of discord. The Navajo (Diné) creation story, for instance, details how the First People journeyed through different colored worlds, encountering various beings and challenges, until they emerged into the present world, learning how to live in Hózhó (balance, beauty, harmony).

The Role of Ancestral Beings and Culture Heroes

In these cosmologies, the figures of Ancestral Beings, Creator Spirits, and Culture Heroes are central. They are not merely characters in a story but powerful entities who continue to influence the world. They established the laws of the land, taught humans how to live, hunt, gather, and conduct ceremonies. Their actions during creation time endowed specific places with spiritual power and left behind lessons encoded in the landscape, flora, and fauna. Respect for these beings and adherence to the laws they established are paramount for maintaining harmony and well-being.

For the Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest, Transformer figures are central. These beings, often Raven or Coyote, traveled the world, transforming elements of the landscape and instituting cultural practices. While sometimes mischievous, their actions ultimately shaped the world into its present form, making it habitable for humans and imparting vital knowledge.

Cyclical Time and Renewal

Indigenous cosmologies often perceive time as cyclical, rather than linear. Seasons, life cycles, celestial movements, and ceremonial calendars reinforce this circularity. The past is not gone; it constantly informs and potentially returns in the present. This cyclical view fosters a deep understanding of renewal, responsibility, and the interconnectedness of generations. Ceremonies, often performed at specific times of the year, serve to reenact creation events, renew the world, and reaffirm the people’s relationship with the Creator and the land. They are not simply commemorative acts but active participation in the ongoing process of creation and world maintenance.

Land as a Sacred Text and Moral Compass

Crucially, Indigenous creation concepts are inextricably linked to specific geographical locations. The land itself is a living repository of creation history, a sacred text where every mountain, river, rock formation, and significant site holds a piece of the narrative. To know the land is to know one’s history, identity, and responsibilities. This profound connection means that disrespect for the land is a disrespect for the ancestors, the creation, and future generations.

The preservation of sacred sites, therefore, is not merely about historical conservation; it is about protecting the spiritual integrity of the people and the continuity of their living cosmology. Disrupting these sites, whether through mining, deforestation, or development, is akin to tearing pages from a sacred book, severing vital connections to the source of life and meaning.

Epistemology and Oral Traditions

The transmission of these complex cosmologies relies heavily on oral traditions, passed down through generations of storytellers, elders, and ceremonial leaders. This form of knowledge transfer is dynamic, adapting to new contexts while preserving core truths. It emphasizes memory, listening, observation, and direct experience. Stories are not just entertainment; they are pedagogic tools, legal codes, ethical guides, and spiritual teachings. The authority of these narratives comes not from written scripture, but from their deep roots in ancestral wisdom, their demonstrated efficacy in guiding community life, and their continuous validation through lived experience and ceremonial practice.

Ethical and Environmental Implications

The ethical implications of Indigenous cosmology are profound. The concept of interconnectedness fosters a deep sense of responsibility and reciprocity. If all beings are relations, then one’s actions toward any part of creation affect the whole. This gives rise to robust environmental ethics that prioritize balance, sustainability, and respect for all life forms. The idea that humans are stewards, not owners, of the land is a direct outgrowth of creation narratives that depict humanity as having been placed on Earth with specific duties to care for it.

The long-term perspective inherent in cyclical time encourages decisions that consider the impact on "seven generations" into the future. This stands in stark contrast to short-term economic gains often prioritized in industrial societies. Indigenous cosmologies offer a powerful framework for addressing contemporary environmental crises, reminding humanity of its rightful place within the ecological web, not above it.

Challenges and Resilience

Despite their profound wisdom, Indigenous cosmologies and their associated practices have faced immense pressures from colonialism, forced assimilation, and the suppression of Indigenous languages and cultures. Many sacred sites have been desecrated or destroyed, and traditional knowledge systems marginalized. Yet, Indigenous peoples worldwide have demonstrated remarkable resilience. There is a global resurgence of interest in revitalizing ancestral languages, ceremonies, and knowledge systems, ensuring that these vital cosmologies continue to thrive and inform future generations.

In a world grappling with ecological breakdown, social fragmentation, and a yearning for deeper meaning, Indigenous cosmology and creation time concepts offer invaluable perspectives. They invite us to reconsider our place in the universe, to listen to the land, to honor our relations, and to recognize creation not as a distant event, but as a living, sacred process that calls for our active participation and respectful engagement. They remind us that the stories of how the world came to be are not just tales of the past, but blueprints for a harmonious future.