Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on "Indigenous Astronomy: The Great Sky River in Tribal Cosmology."

Echoes of the Cosmos: The Great Sky River in Tribal Cosmology

From time immemorial, humanity has looked to the night sky, finding wonder, meaning, and guidance in its luminous expanse. For Western cultures, the stars often represent distant suns, constellations, and celestial mechanics, a realm of scientific inquiry. But for Indigenous peoples across the globe, the cosmos is far more than a collection of physical objects; it is a living, breathing entity, a vast ancestral tapestry woven into the very fabric of existence, guiding everything from daily life to spiritual journeys. At the heart of many of these cosmologies lies a profound reverence for what is universally known as the Milky Way – often conceptualized not as a band of countless stars, but as "The Great Sky River."

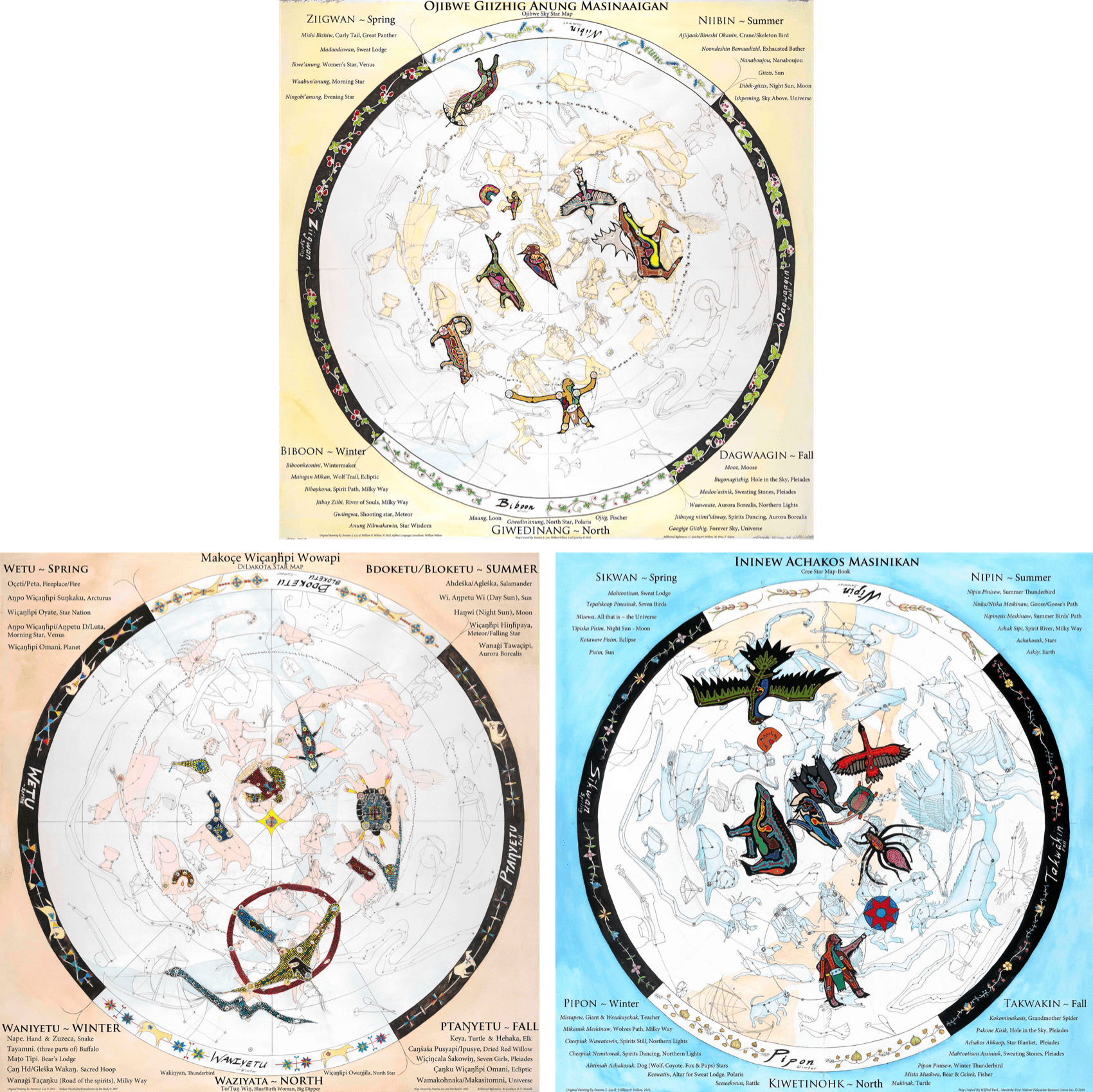

This celestial river, whether a pathway for souls, a cosmic serpent, or a reflection of earthly waterways, is a central motif in the rich tapestry of Indigenous astronomy. It is a testament to sophisticated observational knowledge, deep spiritual connection, and an integrated understanding of the universe that predates modern science by millennia. Indigenous astronomy, or ethnoastronomy, is not merely about identifying stars; it is a holistic science that interweaves celestial observations with land management, seasonal cycles, navigation, ceremony, law, and social structure. It is a living tradition, passed down through oral histories, art, dance, and sacred sites, reflecting a profound and enduring relationship between humanity and the cosmos.

The Milky Way: A Universal Celestial Pathway

The Milky Way, our home galaxy, appears to the naked eye as a hazy band of light stretching across the night sky. While Western science explains this as the combined light of billions of distant stars, Indigenous cosmologies offer interpretations that are often far more poetic, profound, and deeply integrated into their cultural narratives. Across continents, from the Amazon to the Australian outback, from the Andean peaks to the North American plains, the Milky Way takes on myriad forms, yet consistently serves as a central artery of the universe.

For many, it is a river—a source of life, a path for ancestors, or a reflection of the sacred rivers on Earth. For others, it is a cosmic serpent, a bridge connecting different worlds, or the spine of a giant celestial being. These interpretations highlight a fundamental difference in worldview: Indigenous astronomy often emphasizes the relationships and interconnectedness within the cosmos, rather than merely cataloguing its components. The sky is not separate from the Earth; it is an extension of it, a mirror reflecting terrestrial landscapes, animals, and human experiences.

The Emu in the Sky: Australian Aboriginal Astronomy

Perhaps one of the most striking examples of Indigenous astronomical knowledge comes from the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, who possess the oldest continuous astronomical tradition in the world. Unlike Western astronomy, which primarily focuses on bright stars and constellations formed by connecting them, many Aboriginal groups also observe and interpret the dark spaces between the stars – the dust lanes and nebulae that obscure starlight.

The most famous of these is the "Emu in the Sky," visible in the dark lanes of the Milky Way. This giant celestial emu appears during specific seasons, providing crucial information about the emu’s breeding cycle. When the emu appears to be sitting on its nest (in autumn), it signals the time to collect emu eggs. As the emu’s posture changes through the seasons, it guides hunting and gathering practices, indicating when the birds are ready to lay, hatch, or are plump for hunting.

Dr. Duane Hamacher, an astronomer and expert in Indigenous astronomy, emphasizes the sophistication of this system: "This isn’t just a quaint story; it’s a sophisticated, living calendar and navigation system. They are reading the sky in a way that’s completely different from Western astronomy, yet equally valid and incredibly precise." For groups like the Wardaman people of the Northern Territory, the sky is a vast library. Their elders speak of how the stars dictate law, explain phenomena like eclipses, and are intimately connected to their Dreaming stories – the narratives that explain creation and guide ethical living. The Milky Way itself is often seen as a cosmic river or a path taken by ancestral spirits.

The Celestial River Mayu: Inca Cosmology

High in the Andes, the Inca civilization developed an equally profound understanding of the cosmos. Their world, or Pachamama, was deeply connected to the sky, and the Milky Way, which they called Mayu (river), was central to their cosmology. For the Inca, the Mayu was not just a river of light but a celestial counterpart to their sacred terrestrial rivers, particularly the Urubamba River that snakes through the Sacred Valley.

Like the Australian Aboriginal people, the Inca also observed dark constellations within the Milky Way. These yana phuyu (dark clouds) were not empty spaces but living entities, often representing animals vital to their agricultural and spiritual lives. The Llama (Yacumama), the Fox (Atoq), the Serpent (Amaru), and the Toad (Hamp’atu) are some of the most prominent dark constellations. The llama, for instance, was seen drinking from the celestial river, its eyes represented by bright stars. The appearance and position of these dark constellations were crucial for determining planting and harvesting times, understanding animal behavior, and guiding ceremonial practices.

The Inca’s worldview was one of duality and reciprocity, where the sky reflected the Earth and vice-versa. The Mayu was a pathway for the souls of the dead and a source of celestial water that nourished the Earth. Their monumental architecture, like Machu Picchu and the Temple of the Sun at Cusco, was often aligned with significant celestial events, demonstrating an advanced understanding of archaeoastronomy.

The Navajo Sky World: A Tapestry of Order and Balance

In North America, the Diné (Navajo) people view the cosmos as a vast and intricate tapestry, meticulously woven by the Holy People. The Milky Way, known as Yikáísdáhá (the "Way of the Dawn" or "Glittering Road"), is a powerful symbol of order, balance, and the interconnectedness of all things. It is often seen as the path taken by the ancestors or a cosmic thread linking different realms.

Navajo astronomy is deeply embedded in their philosophy of Hózhó, a concept encompassing beauty, harmony, and balance. The stars are not just static points of light; they are living beings, each with its own story and purpose. The constellations, like the "Revolving Male" (Ursa Major) and the "First Slim One" (Orion), are seen as guides and teachers, embodying principles of justice, protection, and agricultural cycles. The hogan, the traditional Navajo dwelling, is itself a microcosm of the universe, with its structure reflecting the cardinal directions and the celestial dome.

For the Diné, astronomical knowledge is not abstract; it is profoundly practical and spiritual. It informs the timing of ceremonies, guides planting and harvesting, and teaches ethical behavior. The knowledge passed down by elders emphasizes that humanity is an integral part of this cosmic order, and disrespecting it can lead to imbalance and illness. As Navajo scholar Dr. Nancy Maryboy explains, "The stars are relatives. They are part of our family. They tell us who we are, where we come from, and where we are going."

Beyond Observation: The Holistic Worldview

What distinguishes Indigenous astronomy from its Western counterpart is its profoundly holistic and relational nature. It is not a detached observation of phenomena but an active participation in the cosmic drama. The "Great Sky River" in these cosmologies is not just a physical feature; it is a source of spiritual power, a historical record, a moral compass, and a practical guide for survival.

- Navigation and Timekeeping: From Polynesian navigators who used star paths to cross vast oceans, to Pueblo peoples who tracked solstices and equinoxes for agricultural cycles, celestial knowledge was crucial for survival and travel.

- Law and Ethics: Many Indigenous legal systems are derived from observations of natural cycles, including those in the sky. The regularity of the stars reinforces the importance of order, responsibility, and reciprocity within human communities and with the natural world.

- Ceremony and Spirituality: Astronomical events often dictate the timing of sacred ceremonies, connecting communities directly to the ancestral and divine realms. The Sky River is often seen as a conduit for spiritual energy and ancestral presence.

- Environmental Stewardship: By understanding the intricate links between celestial events, animal behavior, and plant cycles, Indigenous peoples developed sustainable practices that ensured the well-being of their lands for generations.

The Call for Recognition and Revival

For centuries, colonial expansion and the imposition of Western education systems led to the suppression and devaluation of Indigenous knowledge systems, including astronomy. Many oral traditions were broken, languages lost, and sacred sites desecrated. However, there is a powerful global movement today to revitalize and celebrate Indigenous astronomy.

Scientists, educators, and Indigenous elders are collaborating to document, preserve, and teach these invaluable traditions. Planetariums are incorporating Indigenous sky stories, universities are offering courses, and communities are reclaiming their ancestral knowledge. This revival is not merely an academic exercise; it is a crucial step towards cultural healing, self-determination, and a more inclusive understanding of human intelligence and our place in the universe.

The "Great Sky River" in tribal cosmology serves as a profound reminder that there are myriad ways to understand and connect with the cosmos. It challenges the notion of a single, universal scientific truth, inviting us instead to embrace a plurality of perspectives. By listening to the echoes of these ancient sky rivers, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity and wisdom of Indigenous peoples but also a richer, more nuanced understanding of our own shared home in the vast, star-strewn universe. The sky, after all, belongs to us all, and its stories are as diverse and interconnected as humanity itself.